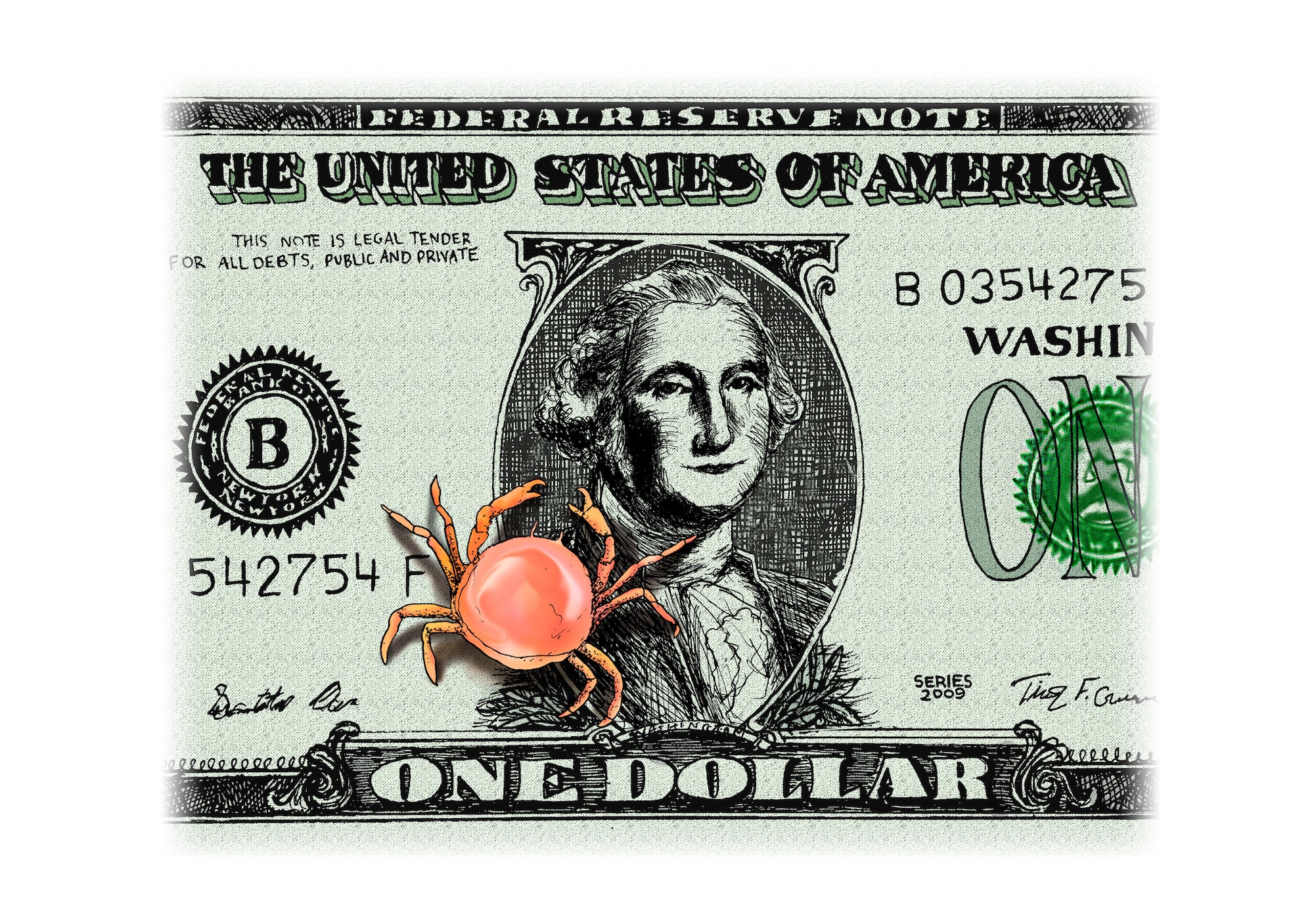

Restaurants that serve oysters sometimes toss out hundreds of tiny, juicy crabs a day—why aren’t they making their way onto the menu instead?

Back in November, I attended an oyster roast on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, where one out of every dozen or so oysters I ate had a bonus treat: a tiny orange crab, roughly the size of a dime, lurking inside the oyster’s shell. Since the oysters had been roasted, the crabs had been cooked along with them. I saw other people eating the crabs whole, so I did the same with one of mine. It was delicious—a bit sweet, a bit briny, and soft with just a hint of crunch.

I mentioned to a guy standing next to me that I’d never seen these little crabs before. “They’re even better when you shuck the raw oysters, because then the crabs are still alive,” he said in a thick Virginia drawl. “I’ll just pop one in my mouth, let him scrabble around in there a bit. That’s what we call a redneck toothpick!” Several other people mentioned that finding a crab inside the oyster was a sign of good luck.

I’d been eating oysters for most of my life—in fact, I grew up in the Long Island town of Blue Point, namesake of the bluepoint oyster—but this was new to me. I soon learned that the little edible creatures are called pea crabs, or sometimes oyster crabs. They enter the oysters (and sometimes other mollusks, like mussels, scallops, and clams) as larvae and then grow to maturity inside their host. Because they’re protected by the oyster, their shells remain soft and slightly translucent. Technically speaking, pea crabs are classified as parasites, because they feed off of the oyster’s food supply, but they don’t harm the oysters.

“The oyster takes in enough food for both of them to be healthy,” says Peter Fu, chef de cuisine at the Grand Central Oyster Bar in New York City. “And the crab doesn’t diminish the oyster’s quality in any way. Really, it’s a sign of a thriving ecosystem.”

If you’re not familiar with pea crabs, there are three likely reasons for that. First, pea crabs are more common in the warmer waters of the Atlantic Ocean, with the Long Island Sound constituting the northern edge of their range. So if you prefer oysters from colder North Atlantic waters, as I do, or from the Gulf Coast or the West Coast, you’re unlikely to encounter them. Second, pea crabs are more common in wild oysters, not the farmed product that constitutes an increasing share of the oyster market.

But the biggest reason you may not have seen a pea crab is that most oyster consumption takes place at restaurants, where shuckers typically pick out any crabs they encounter. “We just discard them,” says Fu, who estimated that the Oyster Bar goes through as many as 1,000 pea crabs on a busy day. “If we miss one, our waiters are trained to tell the guest that it’s natural, like finding a beetle in your salad greens. One time there was a particularly upset customer, so I went out and explained that they’re harmless and also mentioned that George Washington was a great fan of pea crabs.”

That’s right, George Washington. America’s first president has become a posthumous pitchman of sorts for pea crabs. Many published references to them mention that Washington loved having the tiny creatures sprinkled atop his oyster stew, a story that has gained traction among pea crab aficionados. But Mary Thompson, a research historian at Mount Vernon’s Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington, says she’d never even heard of pea crabs, much less of Washington’s supposed fondness for them. “It’s true that Washington loved fish of pretty much any kind,” she said. “But we’ve been plagued for years by stories of one food after another that people claim were a favorite of George Washington without citing a period source. Unfortunately, that makes these stories hearsay at best.”

Sketchy George Washington connections notwithstanding, pea crabs have a rich history and once had a much higher profile. A 1913 New York Times article refers to them as “the epicure’s delight” and describes shucking houses saving the little crabs, blanching them, and then packaging them in glass bottles for retail sale. Pea crabs were also commonly featured in old cookbooks. A 1901 volume entitled 300 Ways to Cook and Serve Shell Fish features 16 different recipes for them (one of which matter-of-factly calls for 500 crabs!).

So what happened? Why did pea crabs become an obscure footnote in oyster culture? “Oyster populations were decimated during the 20th century, which led to a decline in shucking houses,” says Bernie Herman, who teaches Southern studies at the University of North Carolina. “So there just wasn’t enough volume to produce enough yield, especially of something that’s so small.”

Herman, who’s an expert on Southern foodways and also grows his own oysters, counts himself as a big pea crab fan. “I have a pint of them in the freezer right now, in fact,” he says. “After I thaw them, I like to toss them in a mixture of flour, cornstarch, and chipotle chile dust. Then I flash-fry them in peanut oil and serve them on a bed of lettuce with lemon wedges. They’re quite delicious, but it takes a whole lot of oysters to get enough pea crabs to make it worth your while.”

I’ve never seen pea crabs on a menu, but I’ve taken to asking waiters to leave them in the shell if any appear in my oysters.

Herman has solved that problem by striking an arrangement with a Virginia oysterman named Stephen Bunce, founder of the Shooting Point Oyster Company. Bunce ships live oysters to restaurants and markets but also has a shucking operation—so he sets aside the crabs for Herman (and also saves a few for himself to feed to his chickens). “Different areas have more crabs than others,” he says. “A while back they opened up the York River to oystering, and it seems to have a lot more of them.” This caused a problem for Bunce when North Coast Seafood, a major distributor in Boston, noticed the increased incidence of pea crabs in his oysters. “They said people were complaining about ’em, but I told ’em there’s nothing I can do, unless you want me to X-ray every oyster.”

Assuming you don’t have a connection to a local oysterman, your best bet for finding pea crabs is to buy some wild oysters harvested from waters no farther north than the Long Island Sound (Chesapeake Bay varieties are a good bet) and shuck them yourself at home. If you encounter some pea crabs, you can try cooking them—a quick stir in the skillet with some butter does nicely, as does Herman’s flash-frying method—or you can just eat them raw. As with any shellfish, don’t consume them if they’re not alive.

I’ve never seen pea crabs on a menu—and neither had anyone I spoke to for this article—but I’ve taken to asking waiters to leave them in the shell if any appear in my oysters. The live ones taste similar to the cooked ones I first encountered at the oyster roast—a bit sweet, a bit briny. Even when alive, they’re not very active (living inside the oyster shell tends to render them fairly docile), so there’s nothing particularly off-putting about eating them.

Keeping pea crabs off menus strikes me as a bit of a missed opportunity if the Grand Central Oyster Bar is really discarding 1,000 of them per day. “We never really thought about doing anything else with them, but maybe that’s something we could look into,” says Fu, the Oyster Bar chef. “Especially now with the wastED movement, where the goal is to use everything in the food chain.”

Still, serving pea crabs is probably beyond the reach of a more typical seafood restaurant. “I love ’em—they’ve got such a good flavor—but I don’t serve them because we don’t get that many of ’em in our oysters,” says Martha Linton, owner of Martha’s Kitchen in Saxis, Virginia. “One time I put a photo of a bunch of ’em on Facebook—that’s how many crabs came out of a whole bushel of oysters—and one woman thought we were sellin’ ’em and came in here wantin’ to order ’em. I said, ‘Sorry, honey, nobody gets those but me.'”