It took a couple millennia, but rye has finally evolved from a peasant food to a coveted pastry ingredient.

About a year ago, it started to happen. Waffles began to take on a dusky, nutty brown color. Cookies started to gain a tinge of mellow acidity, and pastry crusts developed a rustic heft. Cup by cup, the sweet, glutinous white flour that we were used to was replaced by a glamorously dark and tangy rival: rye.

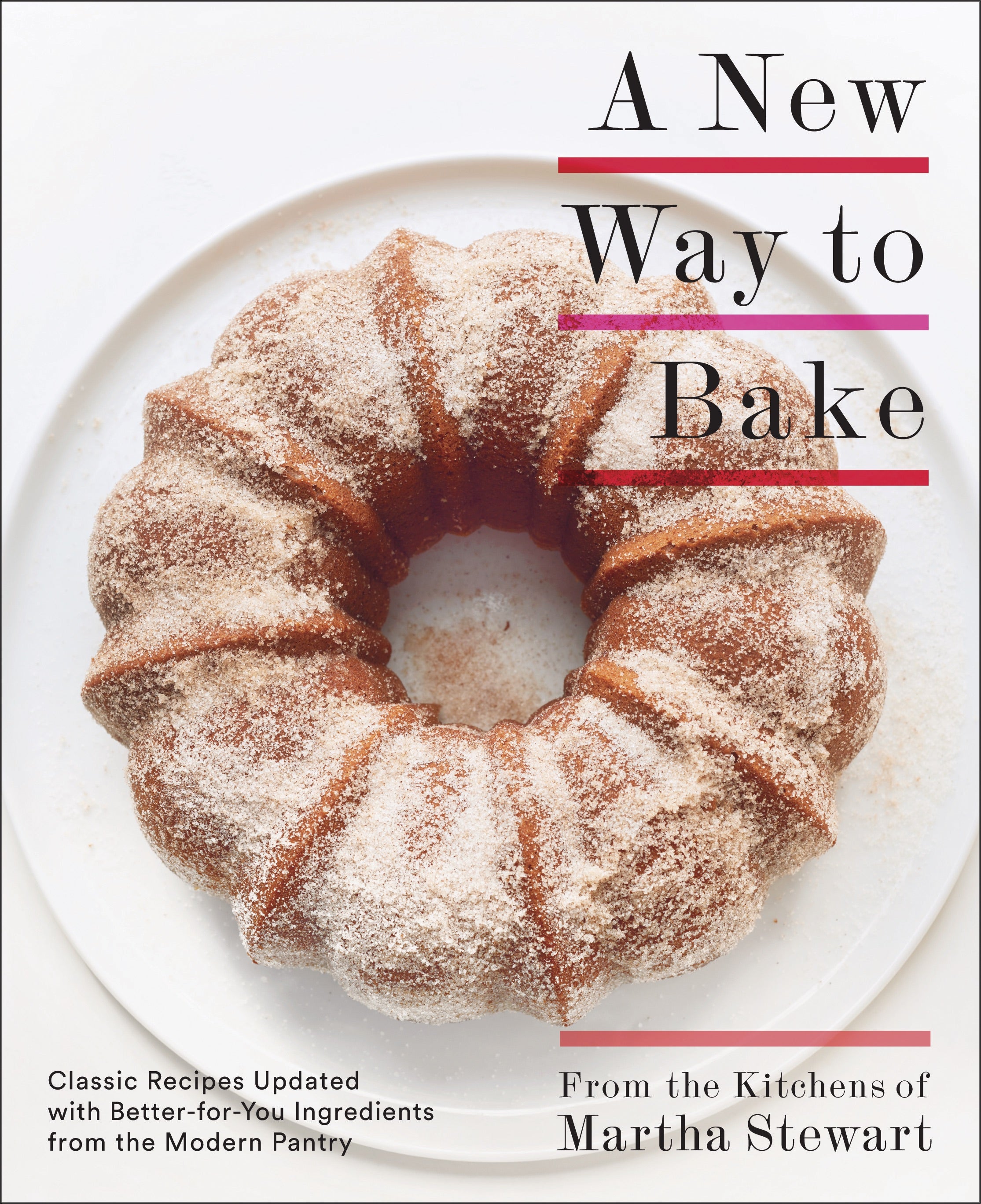

Until recently, rye flour was mostly found in sturdy Scandinavian and Eastern European sandwich breads, but the grain is decidedly having a moment beyond the loaf. Chocolate rye cakes have hit the menus of Tartine Manufactory in San Francisco and Bien Cuit in Brooklyn. Rye cookies and croissants have popped up in coffee shops around the country, and the dark flour has sifted its way into pancakes and pastas. In Martha Stewart’s latest tome, A New Way to Bake, rye takes the form of almond-y cutout cookies, seed-covered soft pretzels, double chocolate muffins, a rhubarb and raspberry crisp, and even a buttery crust for a quiche.

Where did the sudden mania for rye come from? After all, the ingredient had a reputation for literally thousands of years before as a utilitarian workhorse of bakeries and breweries. In the Middle Ages, white bread was a status symbol, and darker grains like rye were relegated to the peasants. Even as early as the first century, Pliny the Elder wrote that rye “is a very poor food and only serves to avert starvation.”

Rye certainly can avert starvation, but it’s also one of the few healthier alternatives to white flour that has its own nostalgic flavor profile. It has less gluten and a lower glycemic index than wheat, and more fiber, iron, and magnesium. But unlike flours from amaranth, teff, or quinoa, there’s something familiar and evocative about it. Instead of reminding us of a health food, it reminds us of the sweet maltiness of rye bread flecked with crunchy caraway seeds that we ate as kids. And how often can we honestly revisit nostalgic foods from our youth for their “health benefits”?

Rather than trying to approximate the taste of white flour, rye has a headstrong character of its own. Since the flavor is strong and since it absorbs more moisture than other flours, most rye baked goods are tempered with a bit of wheat. Bakers love the sour fruitiness of the grain, which makes it a great accompaniment to cherries, plums, rhubarb, and acidic dark chocolates, but the earthy taste holds up just as well to savory foods like eggs, salmon, and herbs. It may have taken a few thousand years to acquire the taste, but now that we have, the possibilities are endless.