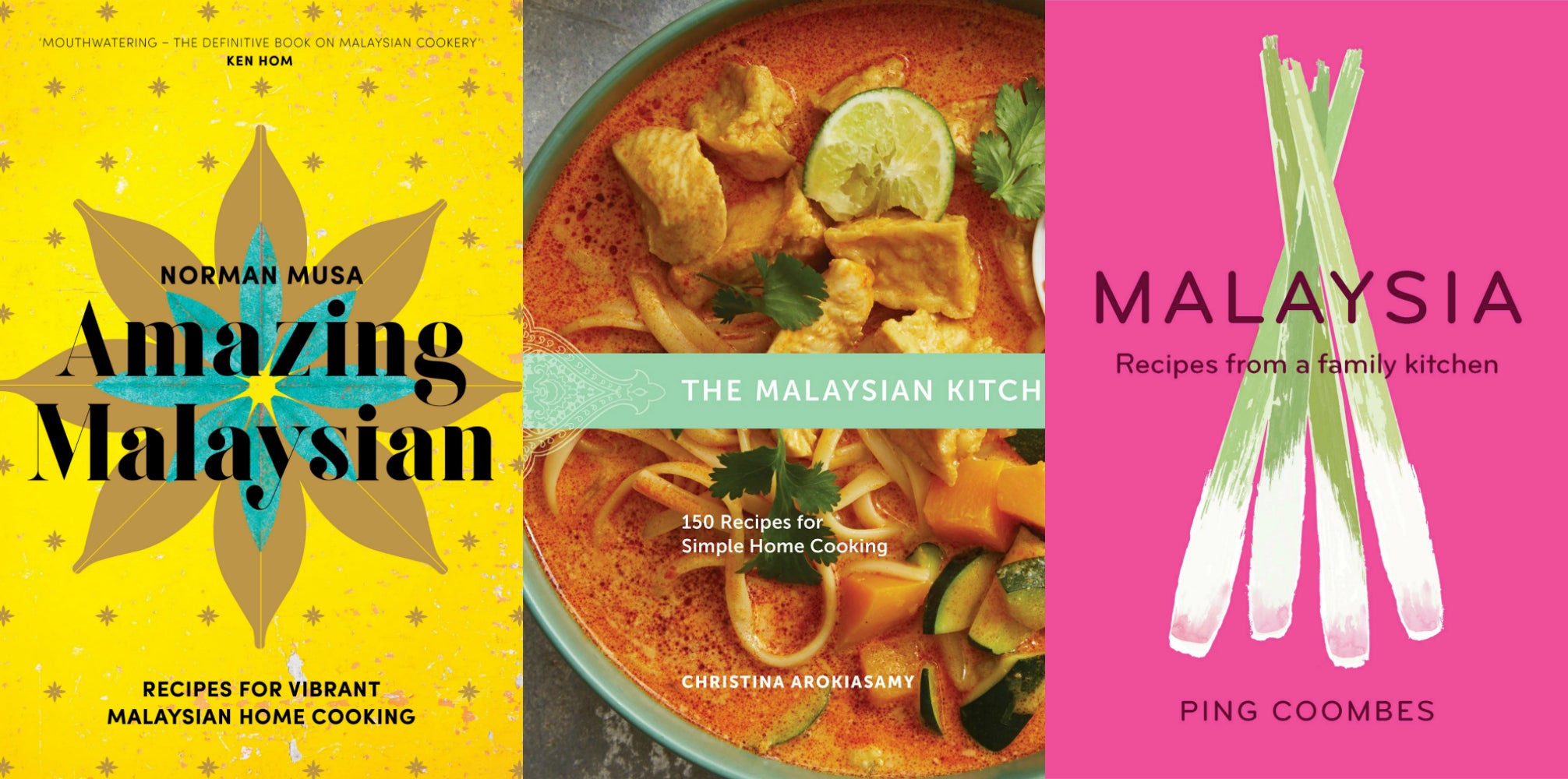

A trifecta of new books authored by a diverse cast of cooks who identify as Malaysian.

When I was two years old, my family emigrated from Malaysia to Arizona. Both places were hot, but that was where the similarities ended—especially when it came to food. Where Arizona was all big-box grocery stores and fast-food chains, Malaysia was wet markets and street stalls. Everything was outside instead of in. Every few years we would travel to Kuala Lumpur and Penang, where my dad and mom were from, respectively, to visit our relatives.

But for me, the visit was really to eat: I adopted my mother’s favorite foods as my own, laksas and curries and satays and noodles and parcels of rice or fish pastes wrapped in banana leaves. I even loved Malaysian desserts, particularly ice kacang, which is a mound of shaved ice with syrup and condensed milk and weird-to-Americans miscellany like beans and corn. And assam laksa, still my favorite food today, and the only food I dream of with regularity—a sweet-spicy-sour and fishy soup with slippery round rice noodles. Eating these dishes outside, seated on plastic stools, everything tasted better there.

“Makan” means “eat” in Malaysia, and if you visit, that’s a word you’ll hear often. “Dah makan?” people ask, which means, “Have you eaten?” That’s the main thing to do. And yet, Malaysian food isn’t entirely easy to describe or put your finger on. It’s a mélange of influences from so many cultures that it’s hard to reduce to a single definition. At its core, Malaysian food means diversity. There are three main ethnic groups making up the population of Malaysia: the native Malays, Chinese, and Indians (mostly from Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka). There are also curries from neighboring India, Chinese dishes brought by immigrants, and Portuguese, British, and Dutch influences leftover from the days of colonialism.

And Malaysian food is that coming together of all these different cultures, unified by shared local ingredients, like coconut and banana leaves and chile peppers. There’s the omnipresent Chinese Hainanese chicken rice—poached chicken served over chicken-fat-infused rice, the cousin of the Thai dish khao mun gai—and street foods cooked in woks over charcoal, like char kuey teow (fresh flat rice noodles tossed with dark soy sauce, Chinese sausage, and shrimp). Traditional, ethnically Malay dishes include rendang, a drier style of curry that’s hairy-looking and sweet with coconut; Indian curries are found all throughout Malaysia. And there’s a small “Mamak” community of Muslim Indians, whose signature dish is the flaky, slapped-by-hand bread called roti canai, which is delicious with condensed milk and banana.

But a good Malaysian restaurant in the U.S. is hard to find—at least, that’s been my experience. Even in California, where I live and where there’s an increasing availability of ingredients like pandan leaf and shrimp paste, Malaysian dishes in so many restaurants imperfectly mimic the food I remember—lacking punch, lacking that perfect balance. My own attempts to cook Malaysian food, guided by online recipes or phone calls with my mother, are no exception. Though I can arrive at a pretty close approximation, it’s never quite the same. It’s always missing something.

So I was excited to see three Malaysian cookbooks released this spring: Norman Musa’s Amazing Malaysian: Recipes for Vibrant Malaysian Home Cooking, Ping Coombes’s Malaysia: Recipes From a Family Kitchen, and Christina Arokiasamy’s The Malaysian Kitchen: 150 Recipes for Simple Home Cooking. Finally, I could learn the secrets to cooking the food I remembered. And I was excited to see that all the books’ Malaysian authors have different ethnic backgrounds: Arokiasamy’s background is Indian, Coombes is Chinese, and Musa is Malay. Multiculturalism defines Malaysian cooking, and so it seems appropriate that this trifecta of books is by a diverse cast of cooks who identify as Malaysian.

In Amazing Malaysia, Norman Musa, who is ethnically Malay, credits his late mother with his cooking. Cooking runs in the family: They sold food from a stall in Penang. In the morning, the dish of choice was nasi lemak, coconut rice wrapped in banana leaves, served with hard-boiled eggs, peanuts, and little anchovies tossed with sambal, ikan bilis. A truly portable breakfast. At night, mee rebus, a noodle dish with a soupy, potato-based gravy, was on the menu. Stalls like the Musa family’s are what Malaysia runs on. Appropriately, his cookbook’s first chapter is titled “Street Food and Snacks” and is filled with the street snacks I miss and fantasize about often.

Ping Coombes is a Chinese-Malaysian chef who competed on the show MasterChef and is now based in the U.K. Her book, Malaysia: Recipes From a Family Kitchen, brims with the sort of Chinese-Malaysian stir-fries and soups my mom would cook at home, too. But first things first, she lays out foundational Malaysian pastes: curry paste, laksa paste, and sambals, which get mixed into soups (think curry laksa) and stir-fries (think sambal prawns). Aromatics get painstakingly pounded in a mortar and pestle, and these pastes lend depth and earthiness to dishes.

Then there’s Christina Arokiasamy’s The Malaysian Kitchen, which approaches Malaysian food with a collection of “simple recipes,” as her subtitle announces. That’s not to say she dumbs anything down: She gives an overview of common Malaysian ingredients and devotes time to demystifying the spices and aromatics that make up Malaysian cooking. Arokiasamy writes: “You never need to feel intimidated by the strangeness of an ingredient. It is as close as your laptop.” Her approach is easygoing and her voice friendly; her recipes are both recognizably accessible.

Each of these three authors offers overlapping recipes, especially when it comes to our common street foods. In each of the books, you’ll find recipes for beef rendang and curry laksa; there are multiple roti canais and slightly varying recipes for satay. But there are also, in all the books, recipes unique to home cooks of different cultures—the meals that get eaten in the family home. I didn’t know much about Malay home cooking, but Musa’s book gives me a glimpse into that world; Arokiasamy, too, gives me a window into Indian home cooking.

Not only are the books an accurate representation of the myriad cooking styles that exist in Malaysia, but they also show the ways in which Malaysian cooks are eager to try whatever is delicious: All the books’ authors include some out-of-left-fielders—meals that don’t appear recognizably Malay.

In Coombes’s Malaysia, there’s a recipe for a hamburger from a Malaysian chain, and a “grilled curry chicken salad” that gets served over quinoa. Arokiasamy offers a recipe for Malaysian-ified American skirt steak. Musa is a professional chef, so he includes recipes of his own invention—especially salads. But that’s sort of the point, too: Malaysian cooks are always open to any new delicious idea.

Growing up, my mother took to making tuna sandwiches with cucumber and white onion for our beach picnics. It reminded me of laksa, which of course it was nothing like. And yet the way she made it, with care and the crusts cut off and the mayo mixed in in just the proper ratio, it was. It’s more the spirit of things—taking different cultures’ cooking techniques, not being afraid to put your own spin on things, incorporating the best of all worlds.

And that’s also the beauty of these three books. They capture that ethos; they reflect that attitude. Though they won’t teach you to cook perfect replicas of hawker fare—that’s some alchemy of charcoal and magic and having to be there, eating while standing in a street in Malaysia—they’ll teach you to cook with openness to whatever it is that makes good food good…wherever you happen to be making it.

If you do try your hand at Malaysian cooking, remember what Arokiasamy says, and don’t be apprehensive about all the unfamiliar ingredients: Things like banana leaves and coconut are now easy to find. Though shrimp paste, which is incorporated into lots of chile pastes, smells scary at first (especially when it’s toasting), it really seamlessly blends into dishes and offers incredible depth and umami.