The incredible story of how chef Kwang Uh opened one of the most celebrated Los Angeles restaurants. And then walked away from it all.

Korean chef. Fermentation lab. Strip mall. Noma. These are the seven words I overheard people using to describe Baroo when it first opened in August 2015. Seven words that would titillate the imagination, capture hearts, and captivate Los Angeles diners—up until its very last day of service, on October 27, 2018. For chef Kwang Uh and his business partner, Matthew Kim, this dream of theirs, built with a meager budget in a Los Angeles strip mall, would set the stage for something extraordinary and beyond their expectations.

ACT 1

Rewind to exactly three years ago. My wife and I are standing outside of a Hollywood plaza featuring a 7-Eleven, a hair salon, an herbal botanica, and a Salvadoran restaurant. We’re looking for Baroo, which has been open for three months, and we’re not the least surprised that it’s in a strip mall. This is Los Angeles, after all, and these nondescript retail hubs are the lifeblood of the city’s restaurant scene—international micro-bazaars of eclectic offerings dotted throughout the sprawl of the city’s 500 square miles.

With affordable rent and decent visibility, strip malls offer entrepreneurs and immigrants the opportunity to realize the American dream. You have driven by them a million times in your own hometown, likely with little regard. But in Los Angeles, if you dig a little deeper, you will eventually find hidden gems, like Baroo.

We finally find it obscured underneath a sun-singed sign with the fossilized typographic remains of a forgettable Thai noodle restaurant once called Joe Noodle. If you didn’t know you were looking for Baroo, you would likely keep walking—unless you were on the hunt for a lottery scratcher, a Latino-style faux hawk, palo santo to burn, or a chubby pupusa.

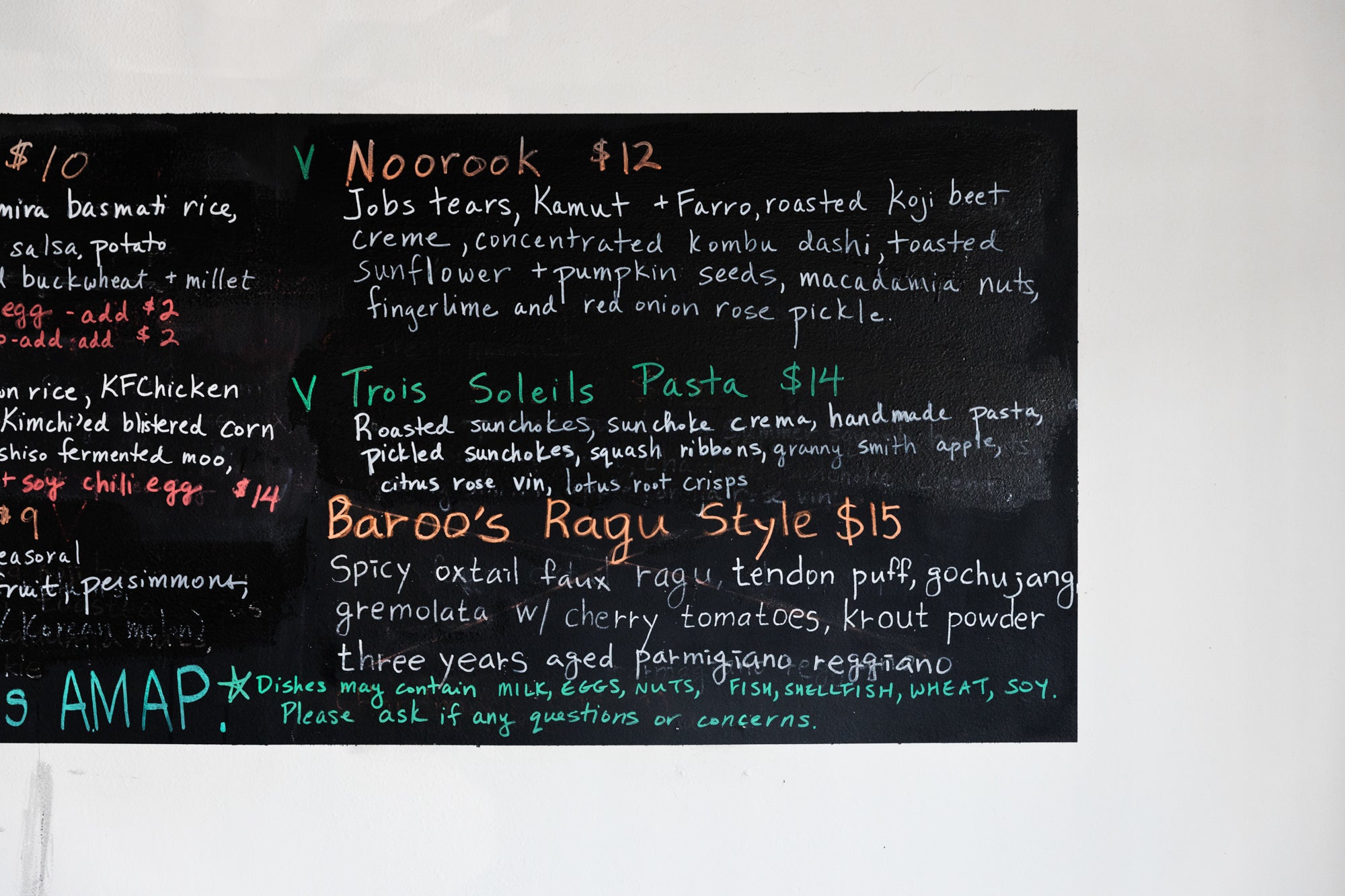

We’re the first patrons to walk into Baroo. No one is dining; no music is playing. There’s not one restaurant employee in sight, only the quiet drone of the kitchen’s overhead fan. The restaurant space is minimal, yet set up with purpose. The furniture is unfashionable yet functional. The new owners apparently wasted no time in opening up shop. We wait patiently and scan the menu etched neatly onto a blackboard. A white shelf showcases various containers of electric-colored pickles, invisibly fermenting.

We tilt our heads, skimming the most eclectic cookbook collection ever curated, noting volumes from France, Korea, Italy, the Basque region, the Middle East—cookbooks that could only belong to an inquisitive mind. We glance back at the blackboard and decide on the pickles, kimchi fried rice, and celeriac pasta. After a few minutes of waiting with no one to attend us, I inch toward the kitchen, looking for any sort of human life. Suddenly, leaning out from behind a wall, we see a smiley Korean guy with short hair tucked underneath a canvas dad hat and thin-framed glasses blinking back at us.

It’s almost 30 minutes past the opening hour, and the sweat on his forehead and upper lip suggests he is in the weeds. He waves at us, from the weeds, with an embarrassed smile, and says, “Just one moment!” And now we notice that there’s another smiley gentleman cooking in the kitchen. He, also bearing a thin glaze of sweat on his face, waves gleefully and bounces back into duty.

We would learn later that these two men, Kwang Uh and Matthew Kim, met in hospitality school and dreamt of opening a restaurant together someday. And that someday has arrived. In a signless but not nameless two-employee restaurant in a strip mall, with no front-of-the-house staff tending to the line of patrons slowly building up at the counter.

Before our impatience starts to bubble over like a pot of boiling water, Uh emerges from the kitchen, chef clogs shuffling hastily across the floor. He takes our order and makes his apologies in the form of house-made kombucha tea to hold us over. Sigh…delicious—tart, as expected, and alive with effervescence. One by one, each dish comes out, starting with the pickles, the kimchi fried rice, and finally the celeriac pasta. Our hangriness subsides as we are about to see why the food has taken so long to arrive.

For those who have not eaten at Baroo, an extraordinary thing happens as you prepare to dine. You are suddenly absorbed into a Being John Malkovich moment; Uh actually gets inside your head and assumes full control of your palate and motor control. Take the kimchi fried rice, which seems like it was born of a wonderful, hallucinogenic trip and is clearly a mislabeled version of the spicy and pungent Koreatown classic. It consists of nearly a dozen unique components.

The “kimchi,” in fact, is made not of napa cabbage but of finely brunoised and fermented pineapple. The crisp, sunny-side-up fried egg that usually crowns kimchi fried rice, is now a 62.5º sous vide egg. The rice is not traditional Korean short-grain white rice, bak mi, but basmati. As a gratuitous bonus, there’s a blossom of Peruvian potato chips, aromatic quenelle’d gremolata, and shiny strips of chewy bacon. Before you can visually process everything in front of you, Uh makes you pierce the egg, mix up the components, and shovel everything onto the spoon in one swift drag.

Widened eyes. Furled eyebrows. Aroused palate. It is utter confusion in the best possible way. The sweetness of the pineapple “kimchi” melds with the bacon fat that has seeped into the basmati rice. The oozy 62.5° egg bursts with no resistance and melts over the thin and crispy Peruvian potato chips like golden lava. No matter which direction Uh makes you drag your spoon in, the textures and flavors work together harmoniously. This overstimulation of taste continues until the very last grain of basmati, and you yearn for more.

Then a nest of gracefully entwined noodles topped with something crispy arrives. Uh, who is still in your head smiling, makes you reach for the empty water glass containing spoons, forks, and wooden chopsticks. You surprisingly grab the latter and begin to fish out strands of al dente, house-made fettuccini lathered with a finger lime cream, crispy celeriac chips, and pickled celery and apple matchsticks. The acidity of the finger lime cream, the crispy, earthy flavor of the celeriac chips, and the firm and toothsome pasta are unbelievably balanced. The pasta, which Uh learned how to make while working at the Michelin-starred restaurant Piazza Duomo Alba in Italy, was never meant to be eaten with chopsticks. Sacrilegious as it may seem to pasta purists, it is an enjoyable and unconventional method of eating that just works. You wonder why you haven’t eaten pasta this way before.

You realize then that Uh has basically taken you on an international carnival ride. There is nothing really Korean about Baroo at all, save for Uh’s ethnicity and select ingredients. Nor is it the cuisine of Spain, Italy, or Denmark—countries where he had worked and developed his palate in. Each dish is its own canvas, constructed unexpectedly and thoughtfully with such attention to detail that it is too beautiful to desecrate with utensils. It is at this moment that I recognize that this restaurant in a strip-mall-turned-food-laboratory in between Hollywood and Little Armenia is culinary genius.

When the late culinary poet and unofficial cultural mayor of Los Angeles Jonathan Gold proclaimed Uh’s food the “Food of the Future” in his 2015 review, the statement unleashed a “gold rush” from all directions. When Bon Appétit named the restaurant one of America’s best, Baroo suddenly found itself completely inundated with the curious and hungry. It seemed as though things could not be any better for Uh and Kim, yet I worried for them. I didn’t get the sense that money was their main objective as much as being creatively free. As months went by, I drove by numerous times, seeing lines out the door—and visually saw them both exhaustingly prepping late into the night for the next day’s service. And I wondered if this was what they even wanted.

ACT 2

Without notice, and when he was needed the most, Uh decided to return to his native South Korea in late 2016. Through the grapevine, we heard that he wanted to dedicate his time to practicing at a small Buddhist temple in South Jeolla province. During his hiatus, Kim would successfully hold Baroo down while fans wondered if Uh would ever return. Before pursuing a career as a chef, Uh had had ambitions of a life devoted to Buddhism. His love for cooking gradually took precedence, but he remained curious about the Buddhist path. Months later, when I made my own trip to South Korea, I wanted to find out for myself what Uh was searching for.

Within 18 hours of landing in Seoul, I was on the high-speed SRT train down to the temple at Baekyangsa (White Sheep Mountain), about three hours south of Seoul. The backdrop quickly gradated from the concrete sprawl and big-city chaos of Seoul to a blur of green brush and blue skies in the countryside—and right away I felt at peace. Uh had told me I could stay at the temple he was working for; I later learned that it was the same temple run by Jeong Kwan, the Buddhist nun and chef first sensationalized by Netflix’s Chef’s Table.

On a cold morning, I was met by Uh at Jeongeup station. He was wearing traditional Buddhist garb (the equivalent of hospital scrubs and monkish sandals), plus his signature canvas dad hat and wire-thin glasses. He looked thinner, possibly due to the absence of late-night ramen and taco-truck adventures in Los Angeles, but his jovial spirit remained unchanged.

We drove in the temple’s utility van through the most serene mountains as Uh pointed left and right like a tour guide. We ascended the main highway and snaked through tunnels for miles. “Down that highway is Jeonju, where the best bibimbap is from,” he said. We weren’t in the chaotic sprawl of Seoul anymore, for sure. I looked over at Uh, who was wearing a tranquil smile; he was in his comfort zone.

The Korea most people might see on TV is a long series of dramas involving young, glamorous, pale-powdered men and women full of life from cosmetic surgery, clothed in the finest designer threads, erratically driving neon McLarens, playing an infinite game of love’s tug-of-war, all to the deceptively addicting soundtrack of Korean R&B and melodramatic pop. But we were near none of that materialism and fabricated drama. The other side of Korea, unbeknownst to many people, is a simple, slower-paced, spiritual side that involves Buddhist monuments, sporadic run-ins with furry creatures, rural villages abundant with giant earthenware—idyllic scenes of nature. And it is something I myself wished I was more exposed to.

“Kwang, L.A. misses you,” I said. “Matthew is doing a good job and everyone loves your food as usual.” Uh smiled humbly.

We drove by a pond, and I recognized from Chef’s Table the string of large stones for crossing, strewn across it like the spine of a dragon. Only there was no Jeong Kwan sitting cross-legged, hands pressed in front of her, engaged in deep meditation. We arrived at the temple, and before I could get out of the van, Uh was already running up some stairs with my luggage into the temple quarters I would be staying in. I arrived to find my carry-on neatly set in the near-bare room beside a rolled-out futon, electric blanket, pillow, and towel. It was November, and we were in the mountains of South Korea—there would be freezing nights for sure. But Uh was nowhere to be found.

Out of the corner of my eye, I spotted him across the temple courtyard peering into various onggi, large Korean earthenware used for preservation. He removed each lid, peered inside, and recovered it, going resolutely down the line of 20 or so. I caught up to him.

“I’m looking for an aged soy sauce for Sunim. We have various ages.”

“Sunim?”

“Jeong Kwan. It’s what we call her. She needs some more soy sauce to prepare our lunch. Try some.”

I dipped my pinkie finger into the murky unknown—so rich with umami, thick like ink, filled with life. The soy sauce (called ganjang) is made at the temple by Jeong Kwan, one of the trifecta of Korean mother sauces, along with doenjang and gochujang. Kwang urged me to remove the lids and taste the other jang, and it was unlike anything I’ve tasted before. Jeong Kwan’s whole cooking philosophy involves working with ingredients grown, foraged, brewed, or fermented on temple grounds. The allium family is banned from her cuisine for its strong flavor and aroma. She believes that cooking should set the mind free and that garlic, onions, and leeks cloud the mind.

I followed Uh into the main house and halted in front of a bald woman dressed in gray, no more than five feet tall, standing still as a deer in the center of the room. Her hands pressed together, she bowed, and I mirrored her. A bit of excitement warmed my neck as I realized she was Jeong Kwan, just like I remembered her from the show.

I introduced myself and shook her tiny hands. She responded with a smile and continued preparing lunch in the kitchen. Standing in the dining room were a dozen or so other people—mainly Koreans in the restaurant industry and a curious cook who’d wandered all the way from Spain, all here for Jeong Kwan’s tutelage of Zen Buddhist culinary philosophy. The team has just prepared a lunch of freshly made tofu, squash soup, porridge and a myriad of foraged vegetable banchan seasoned with the delicious ganjang Uh retrieved just moments before. Simple, motherly, and comforting, and unlike anything you’ve seen in Los Angeles’s Koreatown. I’d only been there for 30 minutes, and already I was starting to understand the angelic allure of Sunim.

Over the course of three days, this collective of various volunteers from Korea and abroad offered their time and labor to learn from Jeong Kwan. Uh and his friend Mingoo Kang, chef-owner of the Michelin-rated Mingles in Seoul, were doing most of the kitchen prep along with the Spanish cook. There was a team of writers, recipe testers, and video crew from Sempio, Korea’s oldest soy sauce and condiment manufacturers, there to research and document Jeong Kwan’s methods of making her jang.

The last day of my stay would be one I would not forget. Uh had asked me earlier what I wanted to eat, and I named kalguksoo—one of my favorite Korean soup noodles. Before we knew it, she was hand-mixing ground vegetable powder with flour to make a vegetable-based dough, rolling it out with a large dowel, hand-slicing the noodles. She happened to sit directly beneath a skylight window with the sunlight beaming over her, almost reasserting her holy presence and dedication to Buddhism.

Everyone was huddled and hovering in between Sunim, trying to document her as well. We quickly learned she is anything but the stoic and pensive nun seen on TV, as she placed some freshly cut noodles over her cleanly shaved head like a lock of hair. She’s quite vivacious, with an innocent sense of humor; the influence she has over everyone is convivial and contagious. The kalguksoo we had was enriching, comforting, and laboriously prepared by the pure hands of a nun. We all slurped and nodded in elation. No one, including Sunim, seemed to mind a bowl of seconds.

To be honest, Uh and I didn’t talk much, nor did I expect to. I made it clear that I would be on the sidelines. There was no need to ask him why he decided to return to South Korea, for I could see how happy he was serving Jeong Kwan. Maintaining spiritual balance, as Jeong Kwan preaches, is key to Buddhist philosophy, and he had found it at Baekyangsa Temple. Witnessing all of this was gratifying for me, and I understood his much-needed detachment from the societal grind.

According to Uh, Baroo was intended to be a free-style experimental kitchen. It was, in a sense, his own temple for spiritual freedom and expression, one that you could actually taste. Uh relates the existence of Baroo to a quote by Zhuangzi, a famous Chinese, Daoist philosopher from the 4th century. Zhuangzi had a dream about being a butterfly. When he woke up, he wasn’t sure if he was a man who’d dreamt of being a butterfly, or if he was actually a butterfly who’d had a dream that he was a man. This quote exemplifies a philosophical issue stemming from the relationship between illusion and reality. Uh believes the first iteration of Baroo was a butterfly dream and even named one of his final dishes after it. Uh is grateful for the media recognition, but it was more in line with a dream than his own reality.

On my last day, we took the train back to Seoul together, and I thanked him for his time. We expressed a mutual hope of seeing each other back in Los Angeles sooner rather than later, but I knew it was really not something for me to decide on.

ACT 3

It’s October 2018 and Uh had returned to Baroo months prior; he and Kim had parted ways to follow new endeavors. The truth about Baroo is that it was unsustainable and merely a temporary culinary experiment between Kim and Uh. I’m standing inside Baroo while Uh, his fiancée, Mina Park—a Korean lawyer-turned-chef—and his team are prepping for their final day of service. A queue of eager guests has already formed, both new and returning, 90 minutes before opening. I swivel around slowly and reminisce about the first time my wife and I came here. The outside “Thai Noodle” sign is intact. The furniture unchanged. Where the cookbooks once were, now an empty void. The blackboard lists a portion of his classic dishes, such as the kimchi fried rice, celeriac pasta, oxtail pasta, noorook and Asian fever. The other menu items crossed out into nonexistence.

A somber yet hopeful Korean song you would hear at the end of a feel-good movie comes on, almost perfectly timed with my bittersweet emotions. The food, first and foremost, was what lured us all here. But it was the humble character of Uh and Kim and unpretentious, unlikely space that kept us returning. Baroo consistently aroused the diner’s palate for three years straight, even while Uh was away. I realize that Baroo was like a traveling circus, a three-year-long one. They set up their camp, people ooh’d and aah’d, and like a dream it suddenly disappeared into the night.

But Uh isn’t as upset as his fans and patrons are. The dream of Baroo has withered away into oblivion, but an unhatched cocoon is set in place for something that will allow Uh to be even more creative. Now accompanied by his fiancée, they’re both concepting the return of a reimagined, rehatched Baroo.

It requires humility to walk away from something even when you’re ahead, and I respect that. We thank Uh, Kim, and the entire Baroo team for creating a time and place with many memories. A vape shop or foot massage parlor will likely fill the void, as they usually do in strip malls in Los Angeles, but we’ll always remember Baroo as a dream we wish to relive. Someday when you’re eating a plate of pasta at home or in a restaurant, you might catch yourself eating it with a pair of chopsticks. And you will smile.