Mastering riz à l’impératrice is a rite of passage for modern pastry chefs. That doesn’t mean you can’t make it at home.

If Kozy Shack is the Hyundai Elantra of rice pudding—dependable, accessible—then French empress rice is something slightly more extravagant.

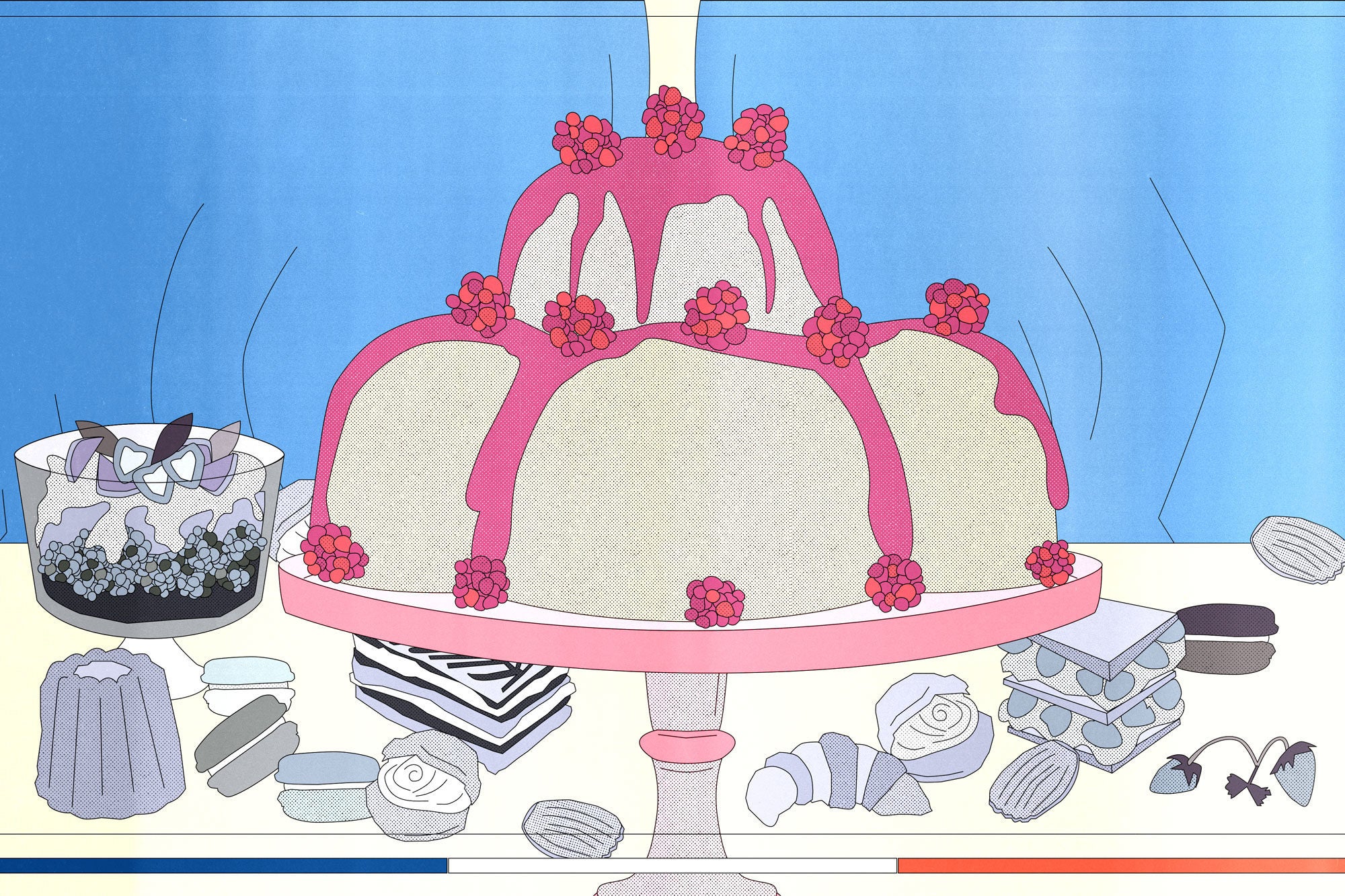

Traditionally, it’s a rice pudding suspended inside a Bavarian, which is a type of cold custard set with both eggs and gelatin that’s lightened with whipped cream. Yes, this does sound weird. Generally, cooks want rice to be either saucy (as in the case of risotto, paella, or congee) or fluffy (pilaf, biryani, or arroz con gandules). But here is a rare case when congealed rice is not only OK, but desired. Imagine a silky rice pudding the color of ivory, in the shape of a Bundt pan Jell-O mold, partially glazed in red, and bejeweled with candied fruit. Molded in place, sliceable or spoonable, the custard allows each grain to stand on its own. Here’s a rice pudding that can be made ahead of time. Here’s a rice pudding that stands the test of time.

“It has this old-fashioned history, but it is one of my favorite things to make,” says Michelle Palazzo, the pastry chef at New York City’s Frenchette. A version of empress rice often makes it onto her menu, usually nestled into a tart shell and covered with fruit—huckleberries, or maybe poached pears. Charmaine McFarlane, the corporate pastry chef for the Terra Momo group in New Jersey, agrees. “Empress rice is a blast from the past. It’s such an underappreciated dessert,” she says.

Even its name is a mouthful: Riz à l’impératrice was named for the last empress of France, Eugénie de Montijo, wife of Napoleon III. The royal couple’s chef, Jules Gouffé, included the recipe in his book, Le livre de cuisine, published in 1884. In his seminal 1903 Le guide culinaire, Auguste Escoffier included a version which he described (in French) as “a Bavarian rice and fruit mold, with a tall jacket of red currant jelly.”

Empress rice waned in popularity in the early 20th century. The American food writer M. F. K. Fisher included a recipe for it—laden with irony and a touch of disdain—in her 1942 manual for smart rationing, How to Cook a Wolf. She calls it “dainty” and “a costly trifle” before admitting that “in spite of its bland intricacy,” it’s “a very gentle dish…somewhat like a notorious actress who is still naive.” Postwar cooks put the starlet back in the spotlight: It reemerged in the 1950s as instant gelatin and became a common ingredient in home pantries. A recipe for it appears in E. Pasquet’s Patisserie Familiale (published in 1958), and another in La Mère Brazier (1977) by chef Eugénie Brazier. It found its way into fancy dinner parties Stateside, thanks in part to a recipe printed in Gourmet in 1951. An illustration of it, tall and glittery as a crown, graced the magazine’s cover that April. The magazine printed another recipe and full-color photograph of it in 1972.

Several decades later, empress rice was reimagined in Desserts by Pierre Hermé, written by Dorie Greenspan. Hermé’s rice tart l’impératrice is a multilayered creation: A Thai jasmine or Arborio rice custard dotted with golden raisins sits inside a buttery tart shell. It gets a slick of red currant jelly and a topper of strawberries, which are seasoned with chopped mint and freshly ground black pepper. It’s no less striking than the dessert Empress Eugénie was served but looks much, much sexier.

Though it lives in the fringes of dessert history, most pastry chefs have heard of it and sometimes serve it, often under different names, because it’s been a mainstay in culinary school curricula practically since Escoffier’s heyday.

In 2004, pastry chef Pichet Ong put a riz à l’impératrice riff on his menu at the (now closed) Spice Market in New York City. “It was a mixture of cooked rice with dried fruit, coconut, vanilla, cinnamon, and instead of the usual pastry cream or gelatin, I folded in whipped cream and then molded it,” he recalls of the dish. It was brûléed before being gilded with fresh passion fruit sauce and seeds. Ong is now the pastry chef at Brothers and Sisters in Washington, D.C., where he pulls ideas from all over the globe. “I have been thinking of revisiting a more traditional variation of impératrice but, you know, with a lot of flavor,” Ong says.

Pastry chef Sebastien Rouxel made a version of empress rice in 2005 at Per Se in Manhattan’s Time Warner Center. When Le Coucou opened in New York City in 2016, pastry chef Daniel Skurnick put a modernized, Jackson Pollock–style riz à l’impératrice on the opening dessert list.

Julie Elkind, the pastry chef at Bâtard in New York City, is also a fan of the holdover dish. She occasionally plays around with rice-based custards, and she loves that the original version is so colorful. “Sour cherries, salted toasted Sicilian pistachios, saffron, lemon…I love pulling in influence from other cultures in decorating it since so many cultures have a sweet rice dish, but I also want it to pop with color and texture,” she says, imagining a modern version.

McFarlane likes riffing on rice puddings, too. She’s done sweet rice risottos, warm rice cakes, and chilled rice custards. “I love the idea of using fresh rice and cooking that in coconut milk. The starch from the rice and fat from the coconut milk add enough structure so you don’t need to add gelatin,” she says.

Taking a note from Palazzo, who often plates hers inside a tart shell à la Hermé, I like to bake a few small rounds of pastry dough as a base for mine. The rice gets rinsed and then blanched in water before it’s cooked in milk scented with a vanilla bean. Once the rice is soft, the milky mixture is folded into a quick custard with a bit of gelatin and some whipped cream.

After letting them set for a few hours in ramekins, I finish them with candied citrus rind, fresh mango, or a spoonful of lemon marmalade and a Luxardo cherry—a bit of gold and royal ruby red, in honor of their regal namesake.