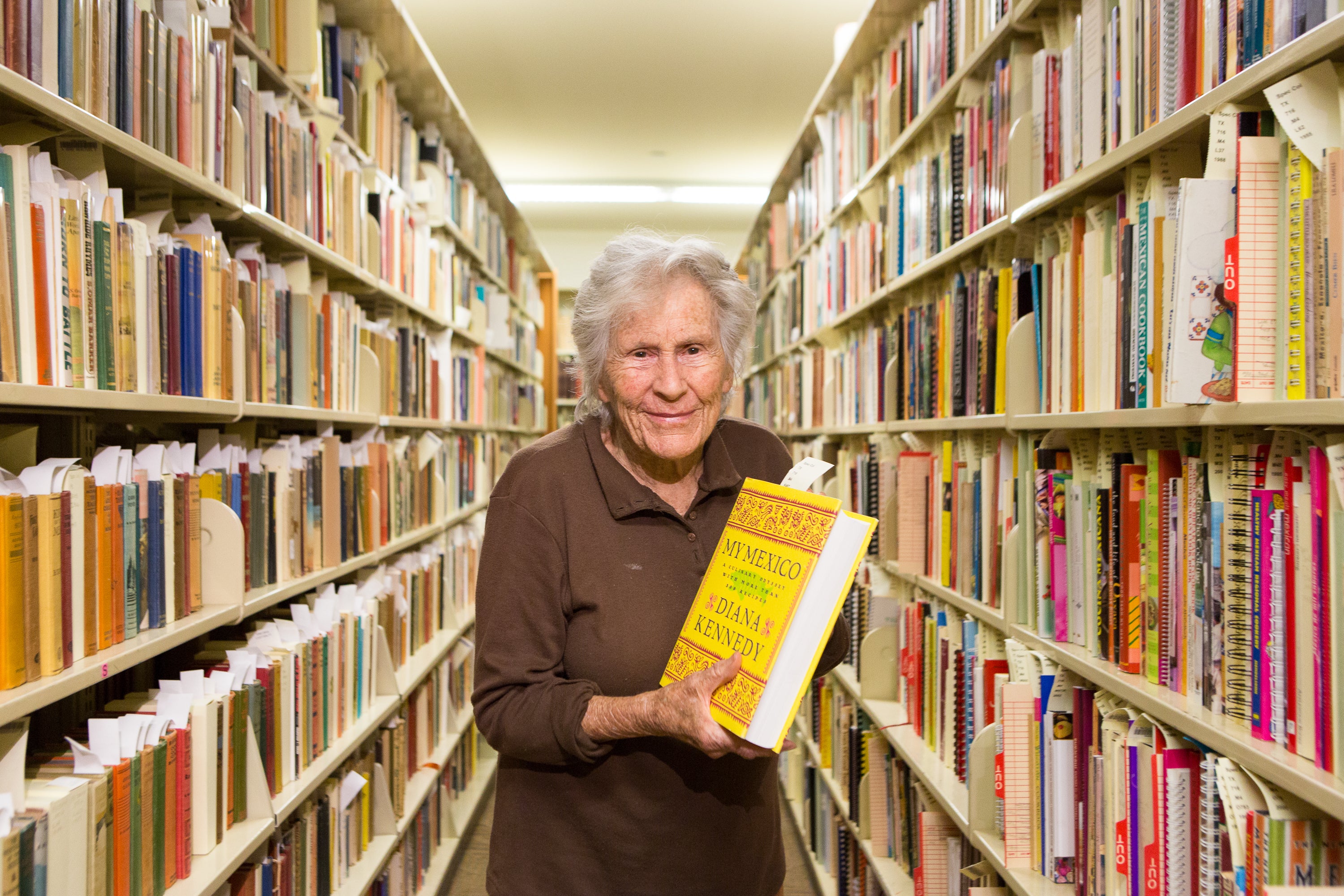

She’s brilliant, terrifying, and a master of Mexican cooking. The 96-year-old writer ends an 840-mile trip from Michoacán to San Antonio with a very special delivery, and some thoughts on a cook’s pickled nopales.

Criticism from Diana Kennedy cuts like a saca tripas fighting blade when the pico de gallo placed before her isn’t correct. But she’s doing the table a favor when saying the acidity is fucked up. No one alive rivals the encyclopedic knowledge of this forceful 96-year-old who, for more than half a century, traveled every region in Mexico while documenting its complex cuisines, camping in her truck, inviting herself into kitchens, hunting flea markets for pre-Columbian ceramics, and most crucially, always crediting recipes to her sources.

We’re together in San Antonio on a recent spring day to pay respect to her treasures. She doesn’t want help getting out of the car. Detests admitting to a cane. (At 18, she joined the British Women’s Land Army in the forestry division during World War II and cut trees for four years. So instead of being killed by a bullet, as she tells it, she developed rheumatism and wound up with two artificial hips.) She presses on, regardless.

If Kennedy has any weakness, it’s for her pit bull mutts, a weekly shot of Dewars, and the Metropolitan Opera matinee broadcast she listens to at home in Zitácuaro, Michoacán, on Saturday afternoons. When something funny strikes her, she has an alto laugh and a wicked grin. Her most sensible pair of shoes are so worn the brown leather has been scuffed off the toes completely. Her Capezio handbag is a tattered mess, full of crumpled tissues and lipstick melting in the Texas heat, but it’s a calculated ruse: Who would pickpocket that?

“Is it true that you keep a pistol under your pillow to ward off intruders?” I ask.

“A .25 caliber,” Kennedy says, her British accent still staccato. “Because, you see, if you shoot them in the foot, they can’t run far, then they have to go to the hospital, and that’s how you pinpoint them.”

Una fiera. A fierce woman.

Her palate is equally terrifying. In My Mexico, the most personal book about her adopted country, she writes, referencing an earlier text: “While the faculties and senses are generally weakened in old age, the palate is strengthened and becomes more sensitive. Because of this, old people lean towards gastronomy.”

She has published eight more books, including the deep dive Oaxaca al Gusto, An Infinite Gastronomy; she’s been awarded the Order of the Aztec Eagle and inducted into the James Beard Foundation’s Cookbook Hall of Fame; and a new documentary on her daily routine in Michoacán titled Nothing Fancy: Diana Kennedy won a special jury prize at SXSW in March. When she’s gone, we will lose Diana Kennedy’s memory of taste. Corn before GMO. The fragrance of wild oregano. The sear of tomatoes roasted on hot stones in a Mayan village. The difference between chile de agua and chile manzano when charred and marinated in lime. Pico de gallo with powdered chile piquín, never cayenne.

Sitting at the same table in 2M Smokehouse is a humbling lesson in rigor as she argues—brown eyes piercing with inquisition—the merits of burnt ends and the inaccuracy of botanas with San Antonio–born pitmaster Esaul Ramos. (She does the same thing with Diego Galicia and Rico Torres of Mixtli when they prepare a spice rub of guajillo chiles not sourced from Zacatecas.) She can’t help herself. Mortality presses, perhaps. Kennedy has always been precise, in both language and recipes, but the urgent conveyance of expertise suggests legacy. Fingers smeared with beef cheek barbacoa, she preaches. In Spanish. For an hour. Mostly about pickled nopales. His jaw drops. Takes an old lady to set a macho on the righteous path, verdad? (Later, Ramos calls me to say he’s going traditional with pico de gallo al Diana.)

“I’m not a Catholic, and don’t believe in the afterlife,” she says with conviction.

What does she believe in? Sustainability. Not just personal but planetary: Childless herself, and a widow since 1967, she advocates for the next generation. This pragmatism has driven Kennedy to finally relinquish her private archive: correspondence with Craig Claiborne and Prince Charles, a massive collection of 35-millimeter slides shot on her old manual Nikon in remote territories during research trips, 12 matchless volumes on 19th century Mexican cooking scavenged over the years in street fairs and other odd places around the country’s 31 states. The earliest is so rare, only one other known copy has surfaced at auction. It sold for $10,000.

Before entering the Special Collections vault in the John Peace Library at University of Texas, San Antonio campus, we stop to sanitize our brisket-smoky hands in the ladies bathroom and she rams down paper fluffed to the brim in the trash receptacle. “No one thinks to do this,” she says to her audience of one. Her own papers will become part of the university’s growing Mexican Cookbook Collection, one of the largest of its kind, with more than 1,900 at present.

From Kennedy’s home among the mountains of the Sierra Madre Occidental, she transported her archival material overland on an earlier trip of 800 miles (one way), chauffeured by a trusted taxi driver to the border town of Nuevo Laredo on the banks of the Rio Grande, where the stacks of papers and memorabilia transferred to a Texan friend’s pickup for the rest of the ride to San Antonio. (Kennedy doesn’t trust the mail.) The working library of 600 books, including copies of her own heavily annotated editions, and other works autographed by such friends as Jacques Pepin, Alice Waters, and Elizabeth David, will come last. She’s not done with those yet.

Her antiquarian books, cradled by foam cushions, wait for us. Head of Special Collections Amy Rushing took Arte Nuevo de Cocina y Reposteria Acommodado al Uso Mexicano to Boston for repair several weeks before. (The university is raising $30,000 to preserve the others.) Published in 1828, it is the first known volume devoted to Mexican cooking. A woven turmeric yellow wool thread was discovered between pages 32 and 33 by the restorers.

“How mysterious,” says Kennedy softly, bending over the little book.

Diccionario de Cocina by Mariano Galván Rivera (1845), published right as Texas was annexed by the United States and the pissed-off Presidente General Santa Anna subsequently declared war, reflects a colonial gastronomy; in this case, menus tracing outside influences in Mexico’s culinary language of the time to France, Italy, Spain, and even England. (Plum pudding with Málaga sauce and the cheesy pastry called conejos galeses or “Welch rabbit.”) Antoine Beauvillers and Marie-Antoine Carême are credited on the title page. The dictionary also contains ephemera—several flowers pressed between its pages. A pansy, faded yellow and dark purple, found in the pescado chapter fascinates Kennedy.

“Pressed flowers! I didn’t know there were pressed flowers. I would never put anything in a book like this, you see. How did I not notice them, I’ve used these books for years. Must have been in there already. I’ve never lent it to anyone. Never lend your valuable books. Ever!”

La Cocinera Poblana (1877), a handsomely tooled red leather volume stamped in gold, is the book Kennedy accredits most in her own writing. A recipe for arroz con chile ancho has a passing mention of saffron, and that sets me to daydreaming how this ancient spice arrived in Spain during the Moorish Caliphate of Córdoba, and then journeyed to the New World, to wind up in the pantry of a wealthy Puebla housewife who possibly missed the wood-fired paellas of her ancestral homeland.

The climate-controlled vault where these books await future researchers of Mexican culinaria is maintained at 58˚F. Kennedy, chilled, cradles her favorites one last time. Fatigue turns her voice raspy.

“They were my companions for life, I hate giving them up, but recognize they have to be under special care, where also they can be used,” she says. “I wanted them to be in a library, I didn’t want them to get to some mediocre chef or certain cookbook authors I do not admire.”

What would una fiera be without her blood feuds?