For 33 years, Cooking Papa creator Tochi Ueyama has taught the comic’s readers that spending time in the kitchen is fun—while quietly subverting Japanese gender dynamics.

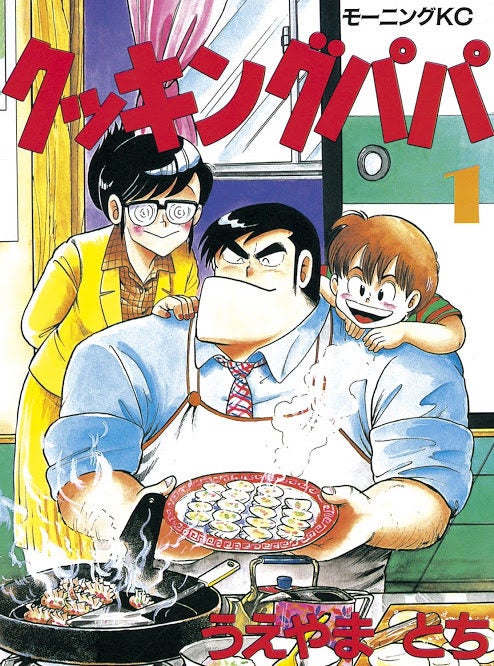

In 1985, the yen was stronger than the dollar, Queen played in Tokyo, and a square-jawed, broad-shouldered businessman named Kazumi Araiwa cooked a stovetop casserole of cabbage and cheese in the first installment of a comic called Cooking Papa. It was a hit from the start, and for more than three decades now, Araiwa has been preparing meals for his children and hardworking journalist wife in the pages of Morning, a popular weekly comics magazine. Each of the comic’s episodes—a dozen or so pages of feel-good narrative, plus a recipe—have been compiled into volumes that have sold over 26 million copies in a nation of 127 million people.

Cooking Papa‘s appeal went far beyond the salarymen it was intended to entertain on their train ride home. It reached an entire generation of readers who had few role models of women working outside the home or men cooking for their families. To this day, gender dynamics in Japan can feel stuck in the 1960s, but Cooking Papa’s creator, Tochi Ueyama, claims he had no progressive agenda. His message is and always has been simple: Cooking is fun.

Comics in Japan are nearly as ubiquitous as TV is in the U.S., with genres encompassing sports, fantasy, nature, romance—pretty much any interest you can think of. There are close to 1,000 so-called gourmet manga—comics dedicated to cooking and eating—and they are often precursors to actual TV shows, like crossover hits Midnight Diner and Samurai Gourmet. Cooking Papa, one of the longest-running gourmet manga, has been translated for Korean and Taiwanese readers and made into a television show that aired for three years. Last year, it was given a retrospective at the Kyoto Manga Museum, complete with a Cooking Papa menu in the cafeteria. It’s a little like The Simpsons is in the U.S.: People know it even if they don’t follow it.

The comic itself reads like a sitcom: a story about family or office life that is quickly resolved. In the comic’s early issues, Araiwa’s boss assumes that his wife prepares his elaborate bento lunches—full of things like grilled fish, neatly cut vegetables and slices of rolled omelet over rice—all wrapped neatly in a furoshiki cloth. Araiwa, not wanting to humiliate his boss or draw attention to himself, doesn’t correct him. He cooks for pleasure and to feed his family and friends, secretly making ice cream in his office and bicycling home each day to prepare dinner while his wife is obligated to stay out late drinking with colleagues. Eventually, as times change, Araiwa does come clean with his boss.

Cooking Papa receives fan mail from readers across genders and generations: stay-at-home mothers, families who read it together, and young adults who bought their first kitchen utensils because of the comic. “Cooking Papa made a large contribution to the culinary industry,” Japanese chef and Iron Chef regular Masaharu Morimoto tells me over email, explaining that he’s seen its influence on the culinary students he teaches in Japan. “It’s fun to read,” he says, “compared to some traditional cookbooks.”

Cooking Papa’s creator has been writing a recipe nearly every week for 33 years. After six months of back and forth with Ueyama’s publisher, they agreed to an interview—the first for an American journalist. I headed to the southern city of Fukuoka, where Ueyama lives and works, bringing my Tokyo-born husband, Hiroshi, to translate (and reassure them I wouldn’t make any cultural blunders). Early in Cooking Papa’s run, Hiroshi was a young reader picking up salarymen’s discarded copies of Morning on the subway and making the potato-chip donburi concocted by Araiwa’s son, Makoto. Araiwa’s family has grown up in the pages of Cooking Papa, but at about half the rate of readers like Hiroshi—Ueyama slows down time so they don’t age too fast.

The entire city of Fukuoka, where Cooking Papa is set, feels like a theme park for the comic’s fans. We rode swan boats in the park where Araiwa jogs and drinks beer with his friends, and ate adzuki ice pops on a side street where some minor characters attend a summer festival. But the biggest attraction for us was Ueyama’s (usually off-limits) studio, a former restaurant that had been built to look like a castle, perched at the edge of the sea.

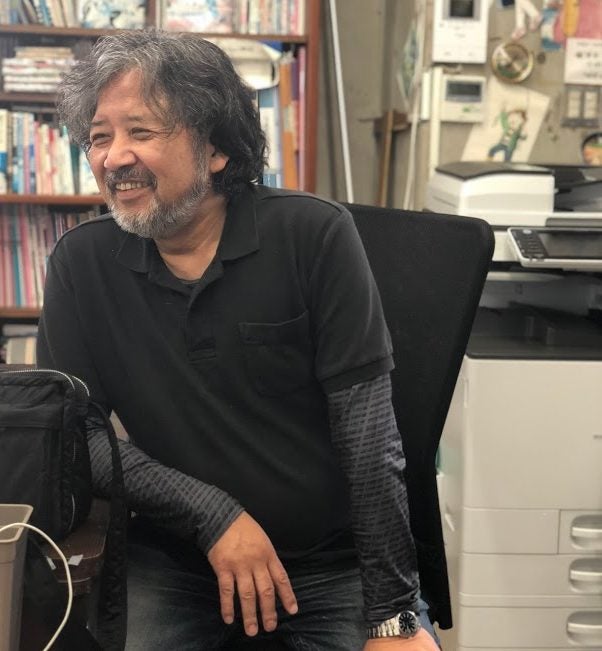

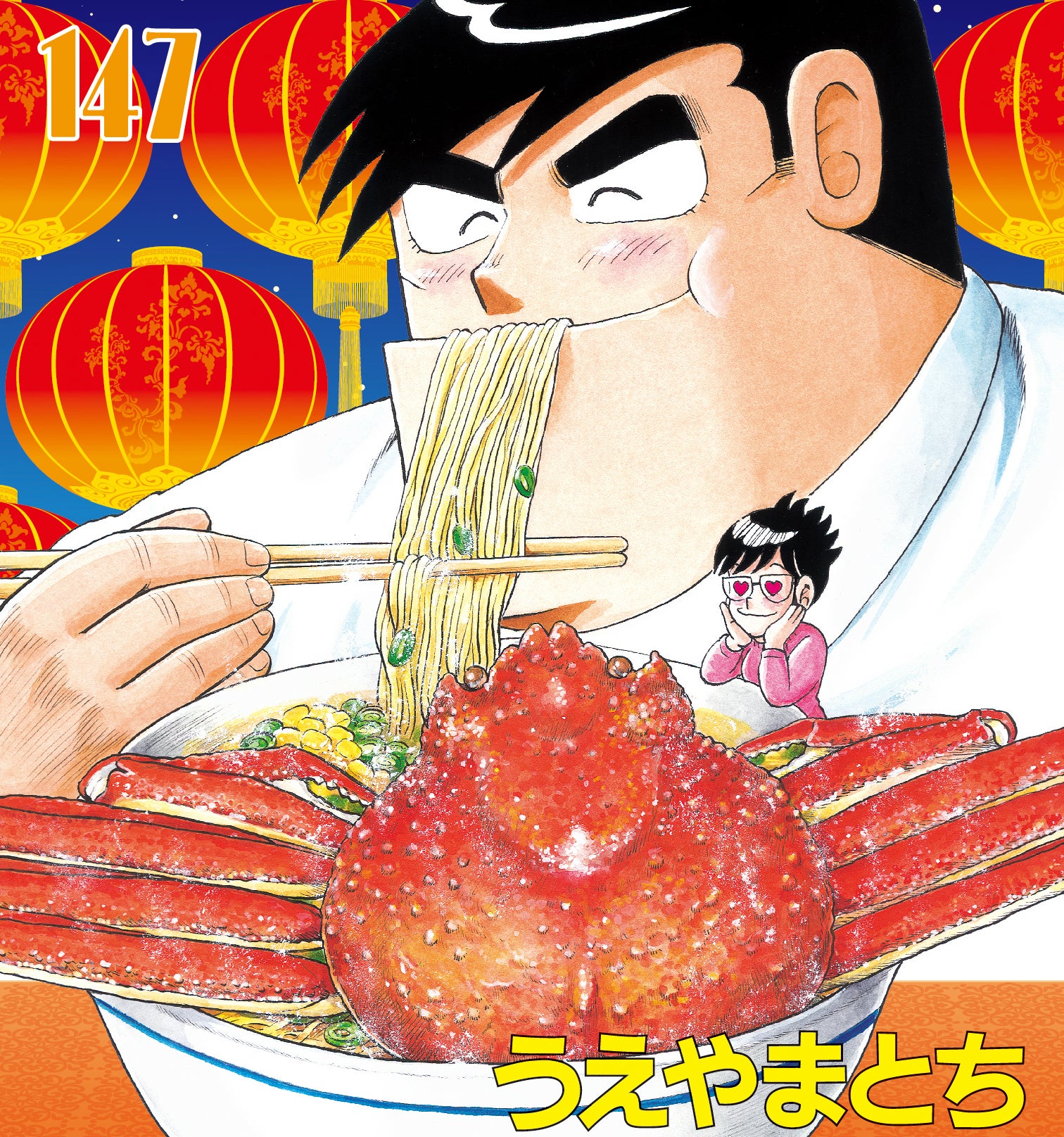

Hiroshi and I were escorted by three people from Morning who’d flown down from Tokyo to supervise the interview. Ueyama descended from his studio at the top of a turret to greet us, down a spiral staircase lined with back issues of Cooking Papa. The 64-year-old author was welcoming but guarded, even verging on grumpy (perhaps bracing himself for the same questions he’s answered a million times). He wore a close-trimmed beard, and wire-rimmed glasses peeked from the pocket of a black polo shirt that hugged his generous belly, which he blamed on too much Hakata ramen (there’s a recipe for this local specialty in episode 9).

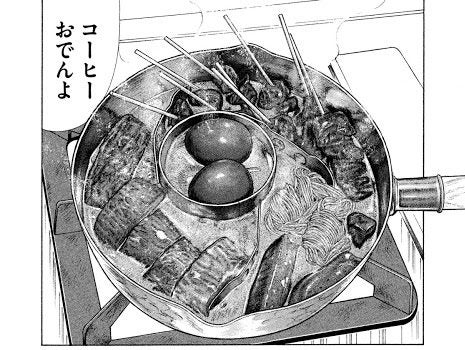

Rows of shiny purple onions and paper-white elephant garlic dried on a table by the entryway. “My wife grows them to sell at the market,” Ueyama explained. I asked him where he got the ingredients for his recipes. “From the supermarket up the street,” Ueyama said. “I want anyone to be able to make the recipes, so I don’t use anything special.” I’ve cooked a handful of these recipes. Like the stories that accompany them, they are egalitarian and consistently satisfying. With some 1,500 recipes, repetition is inevitable. Ueyama estimates he’s done 45 to 50 versions of curry rice, that unglamorous comfort food synonymous with Japanese youth. He does oden every year—in one iteration, the dashi-simmered vegetables and meat are spiked with coffee after Araiwa spills it into the pot, then he decides it’s good.

Ueyama still uses a flip phone; he built his success long before we all had smartphones in our pockets, and his hearty recipes didn’t need to be photogenic.

But onigirazu, Cooking Papa’s mash-up of a rice ball (onigiri) and a sandwich—imagine colorful fillings framed by white rice and black nori—was ripe to become a social media sensation. A few years ago, a fan posted the 1990 recipe on the popular Japanese recipe site Cookpad. Soon it showed up on Instagram, in the pages of Candice Kumai’s latest trendy wellness cookbook (she calls them sushi sandwiches), and on the shelves of Asian delis from Oregon to New Jersey.

In other gourmet manga, food sparkles with fantasy but recipes are vague or unrealistic (a bit like those aspirational videos on social media). For Ueyama, the recipes come first. He begins working on each installment by cooking—photographing every step so his assistants can illustrate the recipe. The story that precedes the recipe emerges from the food itself. Black-and-white drawings—though they’ve become more detailed over the decades—free Ueyama from the tyranny of pretty food. He still shades his illustrations with old-school screen tones cut and placed by hand, rather than using a computer to speed up the work.

Ueyama has a staff of six who work five days a week, from 10 a.m. to midnight, drawing backgrounds and food at desks cluttered with drawings, pens, and brushes. There are bunks for when they have to work through the night. Ueyama still draws all the faces and creates the stories—narratives of Araiwa teaching friends to cook, going on a fishing trip, helping his boss lose weight by eating better, taking his kids to check out local food on vacation, or feeding his tipsy wife when she comes home after a long day. He claims never to get writer’s block. The relentless pace doesn’t bother him, he says. “I decided a long time ago that this wouldn’t be stressful, so it’s not.”

Like his protagonist, Ueyama learned to cook for his younger sibling when they were left at home alone, something that was common in Japan in the 1970s and ’80s. He cooked a rotation of cream stew, miso soup, and curry. “It’s all the same ingredients”—carrots, onion, potato. and meat—“but with different seasoning added at the end,” he recalls.

The similarities between creator and character end there; Ueyama was too busy making comics to cook much for his own family. The few times he made his kids’ bento—slices of steak, or an omelet filling the whole box—they were embarrassed by the odd lunches. So he left most of the cooking to his wife, whom he credits with inventing the viral hit onigirazu.

After our official interview was over, we went to dinner at a seafood restaurant where the conversation turned to Cooking Papa‘s gender dynamics—a dad who cooks dinner and a mom who works late. Unconventional when the comic began, this arrangement remains uncommon in Japan. Ueyama and his current Morning editor, Chika Ichimura, a riot-girl feminist with bits of orange and green peeking out from the edges of her neat bob, talked about the characters as if they are real people. “Nijiko was ahead of her time,” Ichimura observed of Cooking Papa’s wife.

But Ueyama claims he didn’t think much about that. “I made comic strips for newspapers before I started Cooking Papa, and there were lots of women editors and journalists,” he said.

Ueyama refuses to be prescriptive about cooking or gender. Still, his untamed hair and the drum sets and motorcycle helmet back at his studio belied some countercultural tendencies. “If you like cooking, you should cook. If you like working, you should work,” he says plainly. “If you make more money, are you more important? It’s not like that.” Perhaps the most radical thing about Ueyama, and about Cooking Papa, is the attitude that this is nothing special.

With additional reporting by Hiroshi Kumagai and Takuya Kodama. Image Copyright: Tochi Ueyama / KODANSHA.