The bean pie is sweet, custard-like, and a foundationally humble foodstuff. It’s also a culinary icon of the controversial Nation of Islam and of revolutionary black power.

The bean pie’s basic ingredients are simple: navy beans, sugar, eggs, milk, some warming spices, and a whole-wheat crust.

The execution is also straightforward, no different than any other custard-style pie, be it sweet potato or chess.

But the deceptively simple pie is one of the most enduring symbols of revolutionary black power that dates back from the civil rights movement. It has been sold on street corners and in high-end restaurants. It has been referenced in television shows and rap music, and Will Smith feasted on it with friends on The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. Boxer Muhammad Ali even blamed one of his most famous losses on it.

The bean pie came to prominence through the Nation of Islam, a black nationalist and social reform movement founded in 1930. Based on beliefs that included black supremacy and self-reliance, the Nation represented a profound shift from the collaborative social-reform strategies of groups like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Led by controversial figures like Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad, the Nation preached a separatist movement that rejected all enforced doctrines of white society, from clothing to surnames to religion.

Instead, it advocated for a new black identity free from the legacies of enslavement. Christianity, for example, was abandoned in favor of Islam, and surnames given by slave owners were replaced by an X.

Elijah Muhammad addressing a convention in Chicago in 1967. Muhammad Ali sits on the left.

A follower’s diet, methodical and inflexible, was one of the pillars that supported this new identity. The Nation’s leaders argued that many dishes and ingredients traditional to black foodways, particularly soul food, were relics of the “slave diet” and had no part in the lives of contemporary African-Americans.

They also drew a line from soul food—specifically its elevated salt, fat, and sugar content—to the medical woes that disproportionately affected the black community, including high cholesterol, high blood pressure, hypertension, and obesity. Soul food, the Nation’s leaders believed, was just another means through which whites attempted to control and destroy the black population. As Elijah Muhammad, who led the Nation from 1934 to 1975, wrote in his two-book series How to Eat to Live, “You know as well as I that the white race is commercializing people and they do not worry about the lives they jeopardize so long as the dollar is safe. You might find yourself eating death if you follow them.” As a result, the Nation of Islam created its own radical—and somewhat idiosyncratic—new diet for his followers to adhere to, one influenced by both health and identity.

In How to Eat to Live, which was published in 1967, Muhammad emphasized vegetarianism, consuming whole grains and vegetables, and limiting sugar, processed grains, and traditional soul food ingredients, like sweet potatoes, corn, collard greens, and pork—the latter of which was vehemently forbidden to Nation members in accordance with Muslim law. Alcohol and tobacco were also prohibited. In their stead, black chefs cooked with ingredients like brown rice, smoked turkey, tahini, and tofu—which, as black culinary historian Jessica B. Harris writes in High on the Hog, “appeared on urban African American tables as signs of gastronomic protest against the traditional diet.”

The navy bean emerged as one of the Nation’s most important new ingredients; according to Muhammad, all other beans were divinely prohibited. “Do not eat any bean but the small navy bean—the little brown pink ones, and the white ones,” he wrote in How to Eat to Live. “Allah (God) says that the little navy bean will make you live, just eat them…. He said that a diet of navy beans would give us a life span of one hundred and forty years. Yet we cannot live [half] that length of time eating everything that the Christian table has set for us.”

The navy bean was used in a number of new Muslim recipes published in cookbooks and pamphlets, including soups, salads, and even cake frosting. But it was via the bean pie that it truly rose to prominence. The pie’s origins are unclear. Lance Shabazz, an archivist and historian of the Nation of Islam, told the Chicago Reader that the pie allegedly came from the Nation’s original founder, Wallace D. Fard Muhammad, who supposedly bestowed the recipe upon Elijah Muhammad and his wife, Clara, in the 1930s. This claim, however, has never been fully substantiated.

Although Muhammad never explicitly mentioned the bean pie in How to Eat to Live, it quickly rose to prominence in the black Muslim community. With a rich, custard-like filling from starchy mashed navy beans, the pie was generously spiced and pleasantly sweet—a true dessert, despite being full of beans. The beans’ nuttiness, combined with the warming kick of nutmeg and cinnamon, proved an irresistible dish, and soon, as Harris writes in High on the Hog, it could be found “hawked by the dark-suited, bow-tie-wearing followers of the religion along with copies of the Nation’s newspaper, Muhammad Speaks.” Muslim bakeries in cities from New York to Chicago offered it to customers, and “that’s where you would go to buy it, like going to get bread,” says black food historian Therese Nelson. It soon become a staple on the menus of restaurants owned by Nation members.

Lana Shabazz, Muhammad Ali’s personal chef, was renowned for her bean pie, and she included a recipe for it in her cookbook, Cooking for the Champ. As Shabazz wrote, the boxer so loved the pie that he even blamed it for his loss to Joe Frazier in the 1971 heavyweight title fight, having been unable to resist slices during his training.

Eventually, the bean pie became one of the defining hallmarks of the black Muslim diet—a “juggernaut,” to use Nelson’s term, that was a mainstay on dinner tables and in bakeries, and a fund-raising tool to support the initiatives of the Nation in communities across the United States.

One theory behind the bean pie’s potent symbolism is that it not only uses Muhammad’s beloved navy beans but is also believed to use them as a replacement for sweet potatoes, one of the most prominent symbols of traditional black cooking and a direct relic of the so-called “slave diet.” In some ways, swapping sweet potatoes for navy beans in a pie was akin to replacing one’s slave name with an X, as Muslim American historian Zaheer Ali has proposed. By baking the pie, Muslim African-Americans rejected the social bonds imposed by white society and instead created a new identity, in the process establishing their own foothold in American culinary traditions.

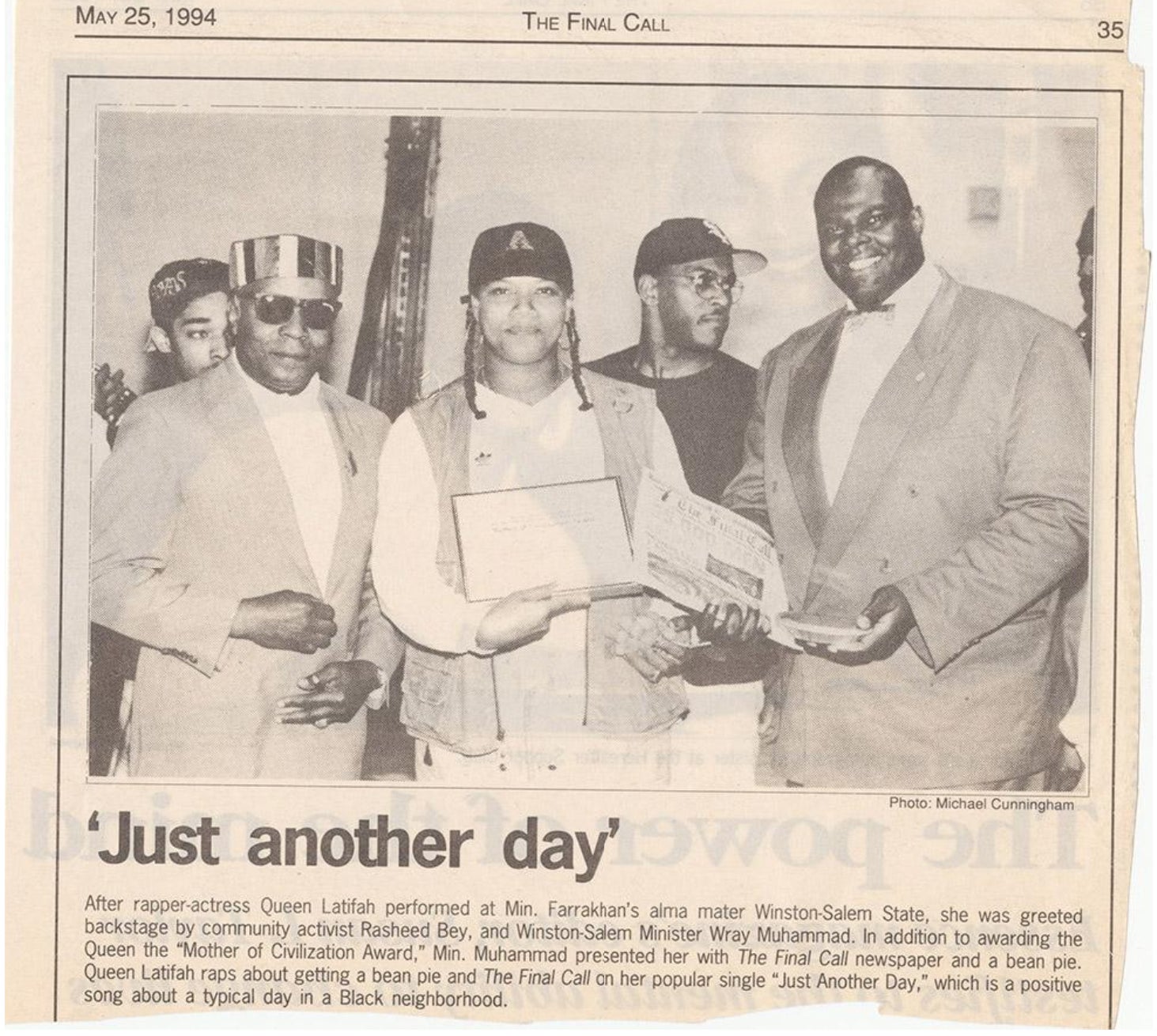

Queen Latifah being presented with a community activism award in 1994, along with a bean pie and a copy of The Final Call (from the Cornell Hip Hop Collection: Bill Adler Archive)

The bean pie has since become a fixture in African-American culture, referenced in rap, comedy, television, and movies, from Queen Latifah’s song “Just Another Day” to In Living Color. It continues to be served after mosque services and sold on street corners both whole and in smaller, snack-size portions, typically with a copy of The Final Call, the Nation of Islam’s newspaper. And of course, the bean pie is on the menu at landmark Muslim bakeries, such as Your Black Muslim Bakery in Oakland and Abu’s Bakery in Brooklyn.

Idris Braithwaite, who runs Abu’s Bakery, says that the bean pie is, in fact, more American than apple pie. Apple pie, he points out, has origins in England, whereas bean pie originated in America. And as Braithwaite tells me, it exists “along the lines of being creative, being innovative, taking sort of what you’ve been presented with and making something unique and awesome.”

It’s a lot of potent symbolism to ascribe to a humble pie, Braithwaite is quick to admit. And despite its powerful legacy, he says, the bean pie “happens to be a great dessert. It tastes wonderful, it looks nice, it smells wonderful. And so, it’s all that and then some.”