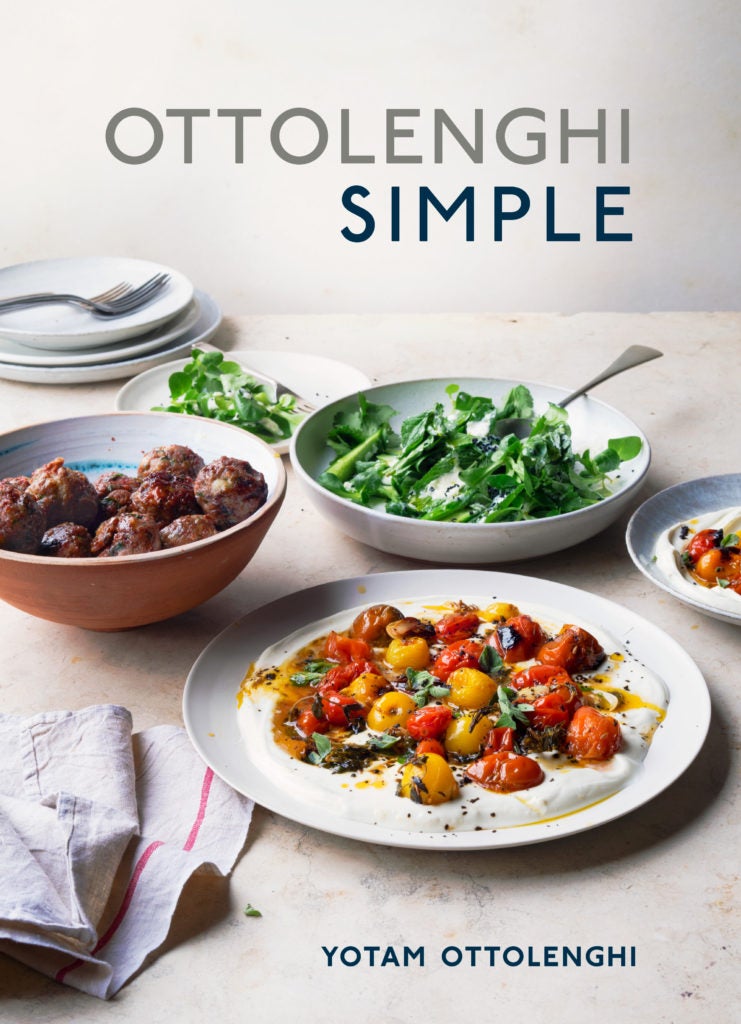

After rewriting the rules of vegetarian and Middle Eastern cooking, the chef is now paring down with a new book: Ottolenghi Simple.

Yotam Ottolenghi is known for many admirable feats. He’s the chef who “sexed up veg,” according to the London Evening Standard, inspiring a generation of home cooks here and in the U.K. (and many other locales) with bright, bold, vegetable-centric recipes that vibrated with both creativity and healthy-ish virtue. He’s the guy who—alongside his business partner and coauthor Sami Tamimi—changed how many of us thought about Middle Eastern cooking and ingredients, with his blockbuster 2012 cookbook Jerusalem inspiring the addition of harissa, za’atar and tahini to kitchen pantries and grocery stores. He’s the owner of five London restaurants and delis that have changed the way London eats, more or less creating a trend around modern Israeli and Middle Eastern food that has made dishes like shakshuka and roasted eggplant with pomegranate seeds part of the city’s diet. He’s the author of six critically and commercially successful cookbooks.

But one thing Ottolenghi is not known for? Simplicity, at least in the easy-weeknight-cooking sense.

That, however, is set to change in October with the publication of Ottolenghi Simple, a cookbook that is built around the idea, Ottolenghi explains, that “there’s more than one way to get a meal on the table and that everyone has a different idea of which way is simple.” As such, the book’s 140 or so recipes are organized and coded according to the kind of simple they are: S—for example—stands for “Short on time,” meaning they take less than an hour to prepare, while I means 10 or fewer ingredients and L means lazy, or the sort of slow-cooking, long-marinating meals that make themselves while you’re off doing something else. E—or “Easier than you think”—could sum up many of the recipes in the Ottolenghi oeuvre—subtract the long lists of occasionally rarefied ingredients and lengthy preparation times and you’re left, essentially, with dishes whose greatest complexity lives in their flavors.

How to best accommodate the highly subjective perception of both simplicity and complexity is something that Ottolenghi has pondered quite a lot over the past few years. “My idea of simple is not your idea of simple, and then a third person might have their own idea,” he says from his home in London. “So you never cook for one particular person; you cook and create recipes for a collective.”

The book, he explains, arose a few years ago when editors at The Guardian, for whom Ottolenghi writes a weekly cooking column, asked him to do a special seasonal booklet of simplified recipes. “I was slightly concerned,” he recalls, “because, you know, I love my ingredients and the processes involved, and looking for things that are special and a little bit exotic.” When he started getting feedback about what “simple” meant to different people, he realized that he could still deliver his flavors “and what people find exciting and exhilarating about [Ottolenghi recipes], but in mind with what would make it doable and achievable for different types of cooks.”

Making recipes more approachable for busy home cooks reflects the publishing industry’s recognition that while fancy, chef-y cookbooks have their uses, titles that marry accessibility with innovation are ultimately what appeal to the greatest number of consumers: Despite our ever-growing sophistication when it comes to dining out, many of us still don’t have the time or the skill to prepare ambitious meals. But at the same time, we don’t want simplicity to equate to a dumbing-down. And in some ways, Ottolenghi himself has broadened our concept of what qualifies as accessible, be it caramelized beets with orange-saffron yogurt or jars of tahini.

“Since I’ve been in the world of publishing cookbooks, people’s pantries have expanded so they’re more comfortable with a wider variety of ingredients. That puts me in a good position, but I never take it for granted,” Ottolenghi says. He knows that not everyone can afford to stock up on, say, harissa or dried Urfa biber, much less find those things at their local grocery store. And he knows that his book’s version of simplicity won’t resonate with every single cook on the planet. “I’ll always have those people who are like, ‘What are you talking about?’” he says. “But once you’ve opened your mind and heart and realize you can get these things online and get back delicious results, then people are happy to cook.”

Photo: Peden + Munk (from Ottolenghi’s 2017 book Sweet)