A botanist, chemist, professor, and tireless advocate for African-American empowerment, he was the Beyoncé of the early 20th-century scientific community.

I have a long-standing crush—of a culinary-history nature—on Dr. George Washington Carver. To be fair, I have many culinary crushes, from Questlove and Eric Ripert going all the way back to James Hemmings and Carson Gulley. But Carver has a special place in my heart for so many reasons, and when I’m done I bet you’ll be as smitten as I am.

When I mention his name—if he even registers with you—I bet your main reference point will be a long-forgotten Black History Month lesson from middle school. You’ll think of the sweet-faced pictures in semiprofile that the history books show memorializing him as an early 20th-century scientist. Peanuts will come up for sure, as will sweet potatoes, and his famous work cultivating them on Southern farms. The thing is: Even if farming-related innovations were his only accomplishments, which they were not, he’d definitely be worthy of a textbook mention. To really get into this man’s life and legacy is to understand how extraordinary and unlikely his story is to begin with, and how many areas—from recycling to crayon dye—his genius truly extended to.

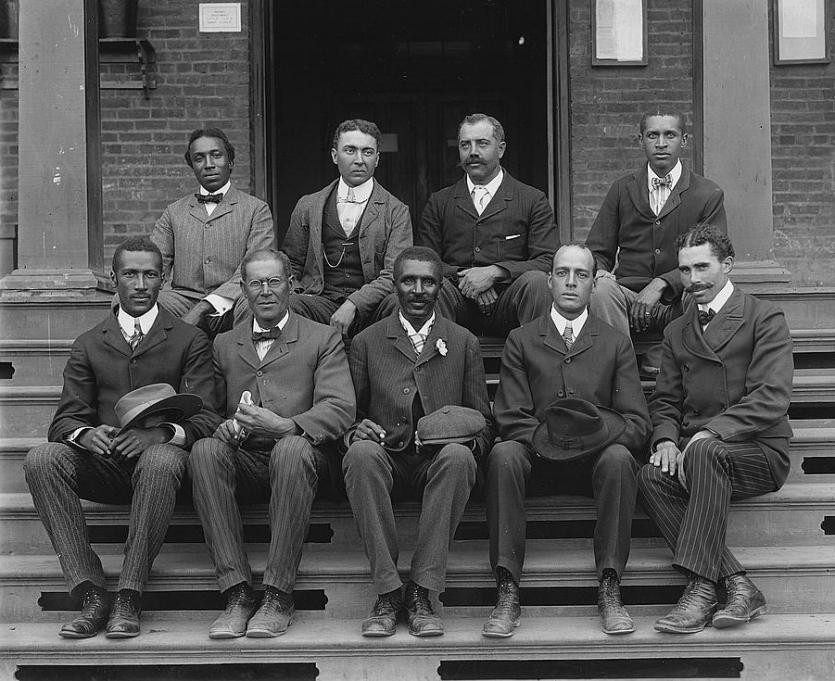

A majority of Carver’s life and career was spent at the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama. When Carver started there, it was a very new and experimental Negro agricultural college. Carver was a young upstart who was sought after by many major universities and corporations due to his wildly successful career as a botanist and chemist. He was the Beyoncé of the scientific community with many, many options. But then Booker T. Washington sent out the bat signal and the rest is history.

Washington was building a modern collective of young, thoughtful, brilliant, and woke black intellectuals to teach and innovate in this new space—and Dr. Carver wanted to be involved. This idea is so compelling to me. It speaks to Carver’s character. He could have taken any number of high-profile jobs, making tons of money and rivaling the celebrity of his mainstream contemporaries, but he felt a calling to a greater good and decided to dedicate himself to educating young people of color so that his work could have the most impact.

One of the main reasons Carver was asked to join the faculty at Tuskegee was to focus his work on helping to expand the new realm of autonomous farming in the black community. In the Jim Crow South, one of the only spaces that black people had any financial latitude was in farming. Carver, like many of his colleagues, had been born into slavery but grew up as the country waged war and the culture was shifting. Carver’s life was molded and informed by this passion for ensuring that formerly enslaved sharecroppers could now reclaim the lands they had historically worked, making this country rich. He wanted to empower these farmers to make better, more fruitful use of the land. This led to his groundbreaking work with peanuts and sweet potatoes.

Carver realized that in order for the black farmer to survive the post-slavery, multinational agricultural world of the 20th century, diversification of crops would be vital. To this end, he introduced a new crop, peanuts, to cotton farmers as a way to enrich the soil and make for stronger primary-crop yields. Meanwhile, he found that there was now potential for using the bumper peanut crop in new industries. This, in a way, saved Southern farming and gave the country a delicious new food in a larger, industrial scale. Enter Carver’s unlikely life as a culinary maverick.

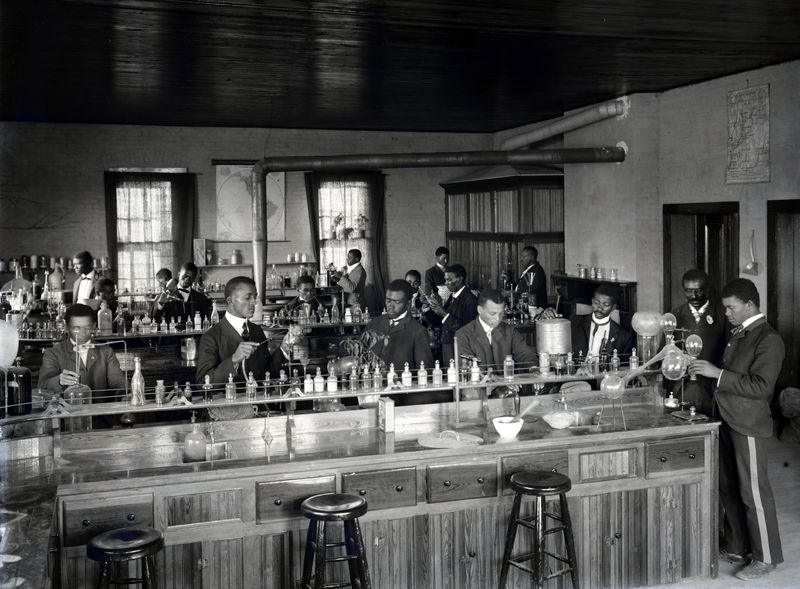

Admittedly the food aspects of Carver’s work are what drew me to him. As brilliant as all his other accomplishments were, I admired his work with food most because Dr. Carver’s understanding, even in the 1920s, of the power of food as an equalizer is still a powerful lesson in the food security and agricultural world. At Tuskegee, Carver had the run of his department with very little oversight. He built his own test kitchen, where he would develop and test recipes. Carver believed you could get people to buy into almost anything if you made solutions edible, delicious, and accessible. In my mind, his approach to cooking was a precursor to the ways we relate to food today. Did this man invent Buzzfeed’s Tasty? I think so. Tasty and other outlets like Food52 only succeed as platforms because the everyday cook is fascinated by the whimsy and the demystifying of that which they find delicious. Carver understood this and planted the seeds for this sort of culinary engagement, utilizing the most cutting-edge resources of his day.

Want proof? He had cookbooks and simple pamphlets, most notably a slim edition called How to Grow Peanuts and 105 Ways of Preparing It for Human Consumption. Buzzfeed! He did the same for sweet potatoes, publishing How the Farmer Can Save His Sweet Potatoes and Ways of Preparing Them for the Table. Food52! The recipes were quirky and relatable and made the reader think more broadly about simple ingredients. He refined recipes for syrups, baked goods, oils, and many other applications that made the farmer and consumer understand and reconsider how to use these uniquely American crops. He used mobile classrooms, traveling from town to town and sharing his research and recipes with farmers and the public alike. This sounds like the first food and wine festival or branded food tour to me.

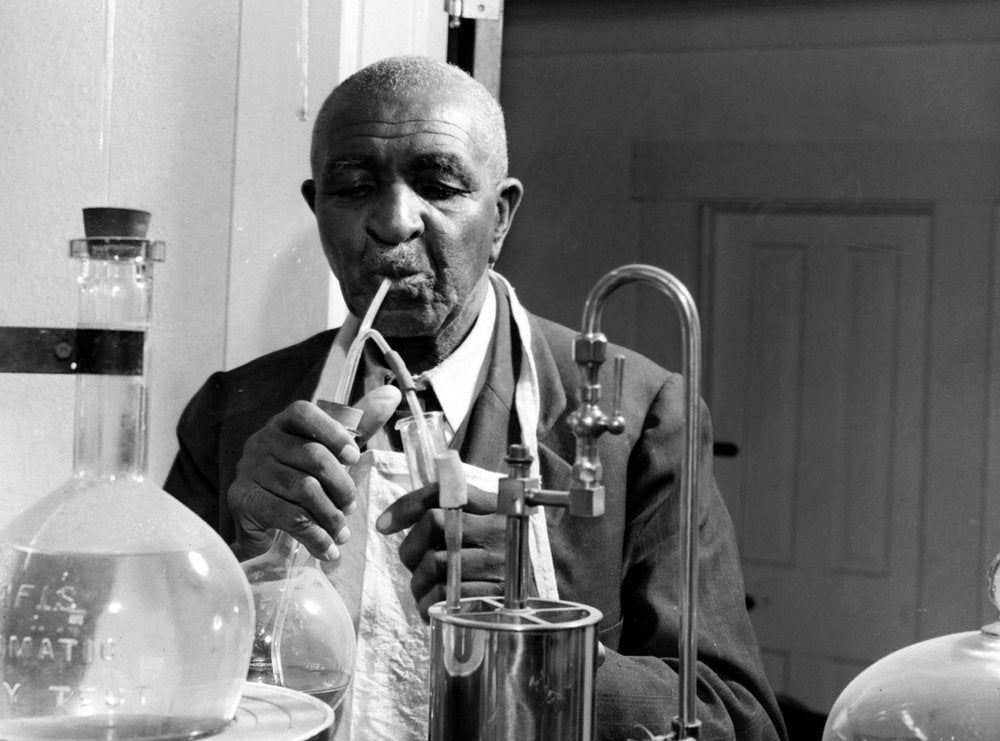

I think of Carver as an all-around creative with multiple outlets of influence. I am most drawn to his unlikely culinary life, but his work is so much broader. He innovated the dyeing industry, making food dyes more organic and affordable. He was an accomplished artist — his botanical paintings and drawing are in the same sphere of dopeness as Georgia O’Keeffe’s. His wartime innovations span three conflicts and include the beginnings of our recycling program and coming up with alternatives to products like rubber and rope that helped us maintain troop supplies. Carver was a creative beast, and yet he lived such a simple and often solitary life.

I am fascinated and awed by all things Carver, but where I am most charmed is by the simplicity of his existence. He was a rock star with public acclaim and access to all kinds of resources, yet he lived modestly in a small apartment on the Tuskegee campus. He never married and spent very little money. He was extremely religious and took almost no credit for his innovations in any monetary way, refusing to patent most of his inventions because he wanted them to remain a public trust. He believed that credit wasn’t as important as having his work be accessible to the public, where it could be of most service. He wanted his discoveries to fuel more work and didn’t want money to be a hindrance to anyone.

This generosity was also evident in how he dealt with his students. He was a passionate mentor and advocate for his students, helping them land lucrative and prestigious positions with the major companies that continually courted his attention. He paid his brilliance forward in so many ways, which to me is the truest example of how clarity of purpose in life makes for extraordinary accomplishment.

The George Washington Carver story is one of black thought and ingenuity being born from a generation that rose above slavery to lay the groundwork for free black life in this country. Carver was a genius, a maverick, an artist, and a scientist—but most importantly he was a black man whose legacy is woven deeply into the fabric of the American experience in a way that transcends race. I think the reason I’m so taken with Dr. Carver’s legacy is that he had so many gifts and found a way to use them all so beautifully. He loved art, so he painted; he was fascinated by nature, so he made his life’s work using nature to improve the lives of everyone around him. It was just that simple.

In all of his work there was a self-assuredness and a clarity of vision that was revolutionary. The combination of humility and brilliance is one of the most attractive and hard-fought balancing acts, and Dr. Carver managed it from his little laboratory, guided by a simple philosophy of decency, hard work, and a trust in his own gifts. What’s not to love and crush on?

RECIPE: Ground Nut Stew