The late Felipe Rojas-Lombardi, an immigrant from Peru, may be America’s most anonymous celebrity chef.

It was 1982 when James Beard learned that Felipe Rojas-Lombardi, a man four decades his junior who had once been his assistant at his cooking school, wanted to open a tapas bar called the Ballroom in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood. Beard didn’t understand.

“Topless bar?” Beard said, befuddled, before he let out a sigh and shrugged. “Well, if that’s what he wants.”

Rojas-Lombardi—a tiny, handsome, scruffy man with hair the color of squid ink—was used to the confusion. Back then, the word “tapas” elicited puzzled glances from most New Yorkers. The traditional Spanish style of serving small plates like the kind Rojas-Lombardi served at the Ballroom struck many as alien. These were tapas of tender, roasted eggplants drizzled with lime juice, garlic, hot pepper, salt, pepper, coriander, and olive oil; and tapas of red beans tossed with parsley and caracoles (snails) that’d been cooked in a brew of garlic, onions, olive oil, white wine, flour, paprika, cloves, cayenne, and beef stock. Some of his dishes, like bowls of a Peruvian stew called altamada, even had chewy little pearls that looked like tadpoles (it was called quinoa), virtually unknown to many Americans at the time.

The Ballroom was a noisy cabaret-restaurant hybrid where fading legends like Blossom Dearie and Peggy Lee performed and sausages and pheasant carcasses dangled from the ceiling as decorative props. The performances were as much of a draw as the food. The entertainment made the Ballroom a destination for the city’s theater crowd, a place where people would flock to see the great divas of the past in the twilight of their careers and have a good time (“rated no. 1 in NY Magazine‘s ‘Great Places to Have a Party,’” read ads plastered in the pages of New York magazine through the late 1980s).

It became one of Beard’s favorite haunts, too. Rojas-Lombardi and Beard, both gay men, were kindred spirits, though Rojas-Lombardi was born and raised in Lima and Beard in Portland, Oregon.

He was the founding chef of Dean & Deluca in 1977, where he became known for some of the earliest pasta salads America had seen.

They kept in close touch until Beard’s death in 1985 at the age of 81. Just six years later, Rojas-Lombardi died, too. He was 46.

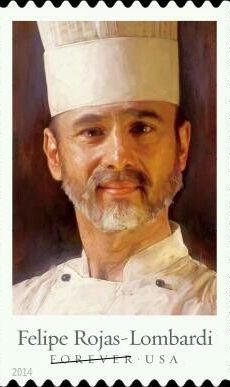

Somewhere along the way, Rojas-Lombardi’s name fell through history’s cracks. In the decades since his death, Rojas-Lombardi has drifted in and out of public consciousness, though he was included in 2014’s “Celebrity Chefs Forever” stamp collection from the United States Postal Service, along with Beard, Julia Child, Edna Lewis, and Joyce Chen. But unlike many of those lauded chefs, Rojas-Lombardi is barely a household name.

When the USPS asked food writer Ana Sofia Peláez to write a short promotional biography of Rojas-Lombardi, she hadn’t even heard his name. “He wasn’t somebody I was familiar with,” Peláez says. “But when I read more about him, it made perfect sense.”

As Peláez dug through archives and microfiches of newspaper stories, she discovered just how trailblazing Rojas-Lombardi was: He parlayed his stint working at the James Beard School into a role as executive chef at New York magazine’s test kitchen. He published a cookbook for kids, 1972’s A to Z No-Cook Cookbook (“It is a gay and light-hearted collection of assembly foods,” Julia Child wrote in The New York Times). He authored “the world’s first talking cookbook,” consisting of two 40-minute cassettes, in 1973.

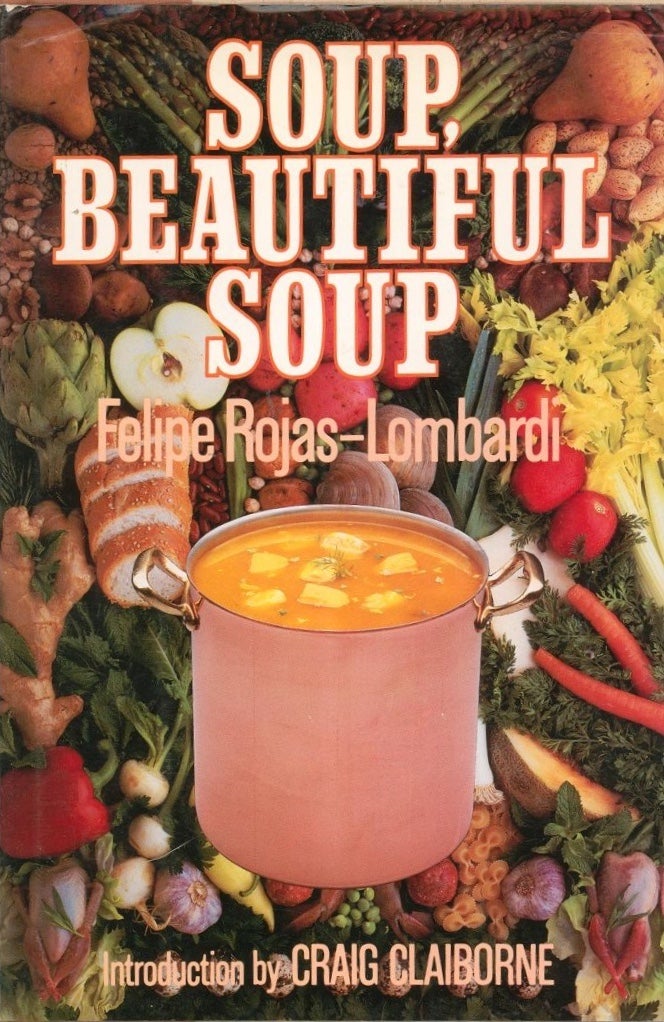

The New York Times’s Craig Claiborne, in his foreword, feted Rojas-Lombardi as “without question one of the most creative chefs in this country.”

He was the founding chef of Dean & Deluca in 1977, where he became known for some of the earliest pasta salads America had seen—and the mere act of serving pastas cold and in salad form constituted a culinary revolution for the era. He got to the Ballroom in the early 1980s, when journalists credited him with introducing tapas to America through his work at the restaurant: There, he made tapas of chicken escabeche, skinny slices of Serrano ham, fried calamari, grilled blood sausage.

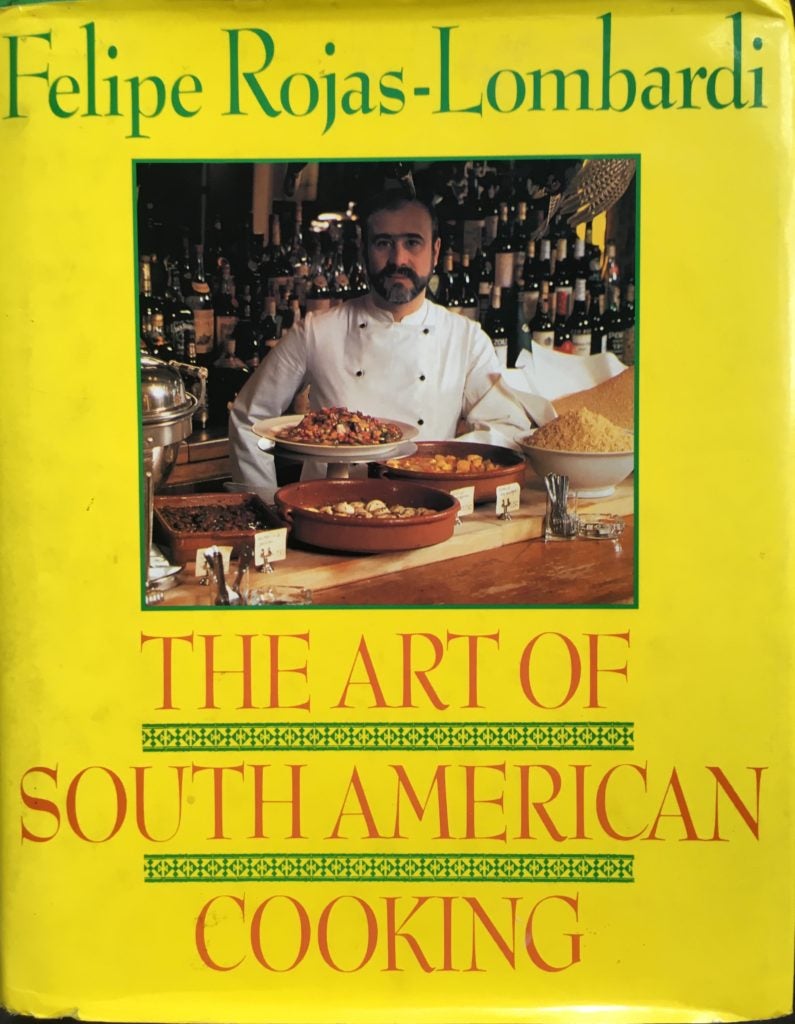

He also wrote two straightforward cookbooks, 1985’s Soup, Beautiful Soup and 1991’s The Art of South American Cooking. Perhaps it’s no wonder that The New York Times’s Craig Claiborne, in his foreword to the former book, feted Rojas-Lombardi as “without question one of the most creative chefs in this country.”

Rojas-Lombardi rose to prominence well before the Internet era, in a time when food television was just embryonic, and it’s tempting to wonder whether Rojas-Lombardi would’ve been more famous had he been around in an era when the medium was more robust. In fact, both his New York Times obituary and Peláez’s USPS biography credited Rojas-Lombardi’s one-off 1985 appearance on an episode of the PBS series New York’s Master Chefs, where he cooked a fish-and-Swiss-chard pie and a bay-leaf-flavored caramel custard, with spawning a number of copycats of his tapas in restaurants across the country.

“Only a few people, even in the food world, writers and chefs alike, know about Felipe, despite the fact that he was quite a figure in New York back in the ’80s,” Peruvian journalist Diego Salazar, who’s been at work on a book about Rojas-Lombardi for the past few years, says. “My guess is he died too soon, and he passed away before chefs truly became big stars.”

Born Edward Rojas-Lombardi in Lima in 1946 to an Italian mother and a Chilean father whose ancestral roots were in Spain and Germany, Rojas-Lombardi was the eldest of six siblings. He was different from kids his age. The other kids idolized Superman, but as Rojas-Lombardi told Gael Greene in 1975, he worshipped chefs. The other boys played sports, kicking around soccer balls in their backyards; he was more attracted to his grandmother’s cavernous kitchen.

Today, I see Rojas-Lombardi’s food as reflecting a queer sensibility in its own right, magnificent and opulent in its presentation, unconcerned with rules that governed what was within culinary bounds at the time.

Rojas-Lombardi briefly attended law school in Peru, as his father wished, before committing his life to cooking. He departed for Europe and spent his time in restaurant kitchens in Spain, Italy, and France, where he cooked with Richard Olney, the gay American food writer who spent the majority of his life in rural France. In 1967, when Rojas-Lombardi was 18, he moved to New York. There, he served as Beard’s protégé for five years. Theirs was a mutually beneficial (and platonic) friendship, according to John Birdsall, the author of an upcoming biography of Beard.

“James actually relied on younger cooks to learn about new foods, new techniques,” Birdsall says. “Someone like Felipe would bring new ingredients, new styles of cooking, new flavors, and the energy James lacked.” The fact that Rojas-Lombardi was gay “also made him family, in James’s mind.”

Today, I see Rojas-Lombardi’s food as reflecting a queer sensibility in its own right, magnificent and opulent in its presentation, unconcerned with rules that governed what was within culinary bounds at the time. This was a man who put veal kidneys on skewers made of rosemary sprigs. His food was intimidatingly exacting and technique-driven, but motivated, too, by a subtle disregard for convention.

To me, this is fundamentally queer. To borrow a page from Birdsall’s own reading of queer food in Lucky Peach, queer food is “food that takes pleasure seriously, as an end in itself,” bulging with energy and messy feeling, electric without sacrificing technical excellence. In an otherwise only marginally charitable one-star review for the Times in 1983, Bryan Miller wrote of the “stunning array of strange and wonderful foods” that greeted patrons when they entered the Ballroom, identifying Rojas-Lombardi as the “conscientious chef who strives for authenticity,” one who “does things the right way, with no short cuts.” Rojas-Lombardi’s food was colorful and unapologetically playful, and he married this sense of culinary whimsy to a dazzling, careful aesthetic. He’d developed a style entirely his own: Beard once told famed food writer Barbara Kafka that Rojas-Lombardi “had the best eye for arranging food of anyone I have ever met,” adding that he “could make anything look beautiful.”

But the matter of Rojas-Lombardi’s sexuality, at least in public, was unspoken. Even his lifelong romantic partner, Tim Johnson (who died in 1997), was referred to as Rojas-Lombardi’s “business partner” in obituaries. The silence surrounding sexuality was a condition of cultural attitudes at the time.

“Nobody thought about their personal lives,” Caroline Stuart, who worked under Beard in the late 1970s, says of both Beard and Rojas-Lombardi. “They were just thought of as chefs.”

According to Stuart, Beard visited the Ballroom often after it opened; Rojas-Lombardi treated him like a king. “When Jim would go, they would just bring him everything they could fit on the table,” she says. Beard and Rojas-Lombardi talked on the phone regularly until Beard’s death in 1985.

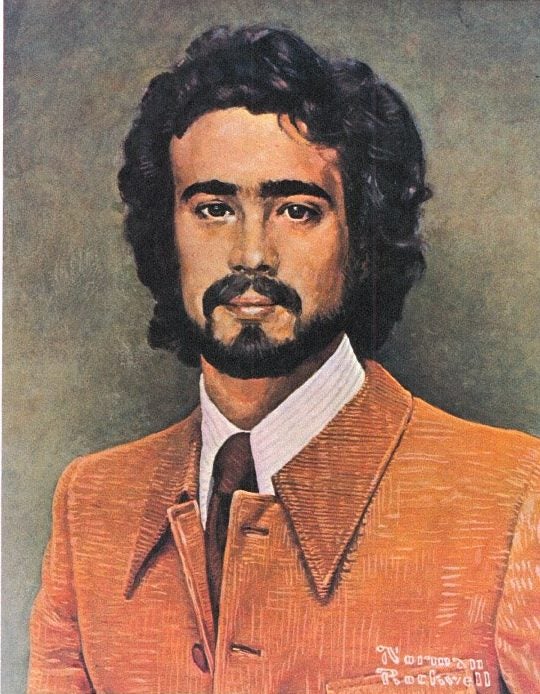

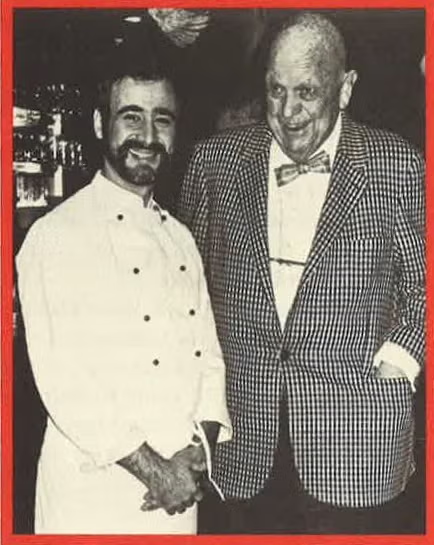

Felipe Rojas-Lombardi and James Beard (courtesy of the James Beard Foundation)

“He liked Felipe a lot,” Stuart says, mentioning that Beard kept a framed portrait of Rojas-Lombardi in his dining room. “Everybody liked Felipe.” Rojas-Lombardi dedicated his first cookbook, 1985’s Soup, Beautiful Soup, to the memory of Beard.

It was 1983 when chef, food historian, and cookbook author Maricel Presilla met Rojas-Lombardi. Back then, she was a doctoral student finishing a dissertation on medieval Spanish history at New York University; she never thought she’d work in food. The course of Presilla’s life changed when she wandered into the kitchen of the Ballroom to visit a chef friend, and Rojas-Lombardi approached her.

“He said, ‘Why don’t you wear an apron and start cooking?’” Presilla recalls. Presilla was confused, but she put on an apron and made flan. Rojas-Lombardi loved it and decided to sell it at the restaurant.

“Felipe and I immediately established a rapport, both being from Latin America,” Presilla, a native of Cuba, remembered. She agreed to work at the kitchen of the Ballroom once a week, and she stayed there for years.

Through it all, Rojas-Lombardi’s vibrant culinary personality and playful, precise aesthetic attracted patrons. “That was before the Health Department got into people’s lives and made life awful for everybody,” Presilla says, laughing. “Today, he wouldn’t be able to have those dead ducks and turkeys and codfish hanging from the bar. It looked like one of those Renaissance feasts.”

Things changed in 1989, when Rojas-Lombardi got sick with degenerative osteoporosis. He had recently begun working on a cookbook and enlisted Presilla’s help in writing recipes. The book that resulted from this, The Art of South American Cooking, is ambitious and expansive in scope, over 500 pages long, aspiring to be a definitive volume on a whole continent’s foodways.

The book came out in the fall of 1991, just after his death in September. Presilla took a proof of the book to the Cabrini Center in the East Village, where Rojas-Lombardi was staying, the night before he died.

“His death was a blow to us,” Presilla says. The Ballroom just wasn’t the same without him, she says; it closed its doors for good in 1995. “They tried to keep things the way Felipe had them, but it just did not work.”

It’s been decades since Rojas-Lombardi died, but Presilla still feels his spirit. He lurks as a textual presence within Presilla’s writing; in the acknowledgments of last year’s Peppers of the Americas, she mentions her “dear late friend chef Felipe Rojas-Lombardi.” She inherited his semi-monstrous cookbook collection and revisits these cookbooks often. She remembers her days in the kitchen of the Ballroom clearly. The chocolate tart he once made her for her birthday, topped with candied violets and gilded gold leaves. The way he moved, the way he looked.

“He was small, very beautiful, but he had this larger-than-life persona,” Presilla says. “He was a giant.”

Illustration by Natalie Nelson