Over the last several years, yogurt has taken a savory turn. Books like Yogurt by Janet Fletcher (Ten Speed Press) and Yogurt Culture by Cheryl Sternman Rule (HMH) prove just how versatile it really is. And then there’s the booming popularity of Middle Eastern food, a cuisine that uses thick yogurts as dips, for dolloping over stews, and for stuffing into vegetables.

This brings us to labneh (also spelled labne or lebneh). In some cases, the difference between Greek yogurt and labneh is slight. “Both are yogurts that are strained to remove at least 50 percent of the whey,” says Louella Hill, author of Kitchen Creamery (Chronicle Books), a book about making cultured dairy products at home. “The difference between the two is often in the application. We think of yogurt as going more sweet—with things like cherry jam—while labneh goes more savory, with olive oil and za’atar.”

Labneh is often (though not always) more strained than Greek yogurt, so it’s ultra-thick and spreadable, almost like cream cheese. Plus, labneh is frequently seasoned with salt and lemon juice to give it a more cheese-like savory flavor. “The thickness can vary from house to house, from producer to producer,” says Hill.

In parts of the eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East, including Turkey, Lebanon, and Israel, labneh with olive oil and za’atar is a typical breakfast. In chef and restaurant owner Rawia Bishara’s excellent cookbook Olives, Lemons & Za’atar (Kyle Books), she describes her mother making the labneh they ate for breakfast where she grew up in Nazareth from goat’s-milk yogurt and preserving it in olive oil.

At Middle Eastern restaurants in the U.S., you’ll often find labneh—usually made from cow’s milk—as part of the mezze menu, which features small, sharable dishes that come before the larger ones. Of course, as when any ingredient becomes trendy, chefs are taking labneh out of its traditional context and using it in new ways. At Mission Taqueria in Philadelphia, for example, you’ll find labneh blended into a calabaza (a type of pumpkin) soup. At Souk in Washington, D.C., labneh is veganized and made out of cashews.

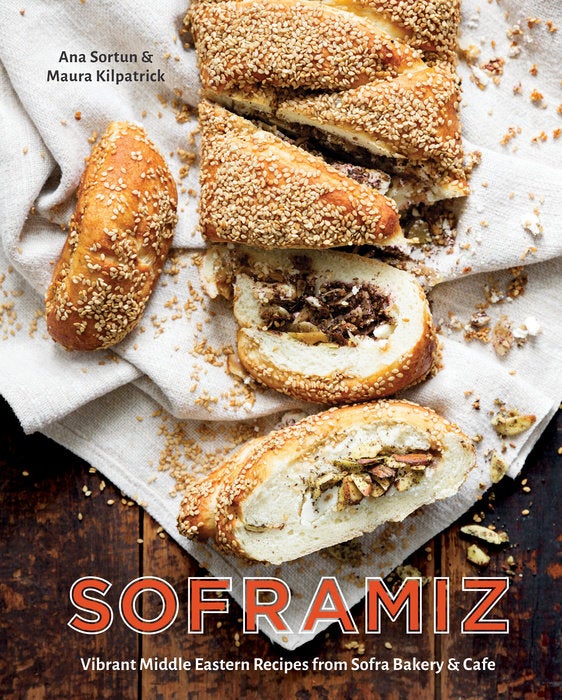

For now, it’s hard to find commercially made labneh outside of Middle Eastern markets. No matter: In their cookbook, Soframiz (Ten Speed Press), Boston-based chefs Ana Sortun and Maura Kilpatrik say cooks can use whole-milk Greek yogurt as an alternative to labneh in their recipes. It’s also easy enough to make your own (see their recipe below). If you go this route, don’t toss the whey—drink it straight or use it in smoothies, as a brine, or in baked goods instead of milk or buttermilk.

You only need one ingredient to make labneh.

DIY LABNEH

1. Line a colander with cheesecloth and place a mixing bowl underneath it to catch the liquid that drains from the yogurt.

2. Put 4 cups plain whole-milk Greek yogurt (the ingredients should include only milk and cultures and no thickeners) in the colander and wrap the cheesecloth over the top. Place a small saucer or plate on top to lightly press it down.

3. Refrigerate at least overnight, and up to 2 days before transferring to a container. Store covered in the refrigerator for up to 10 days.

Recipe excerpted from Soframiz by Ana Sortun and Maura Kilpatrick, copyright © 2016, published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.