For decades, cookbooks were primarily written for home cooks, by home cooks. And then the ’90s arrived.

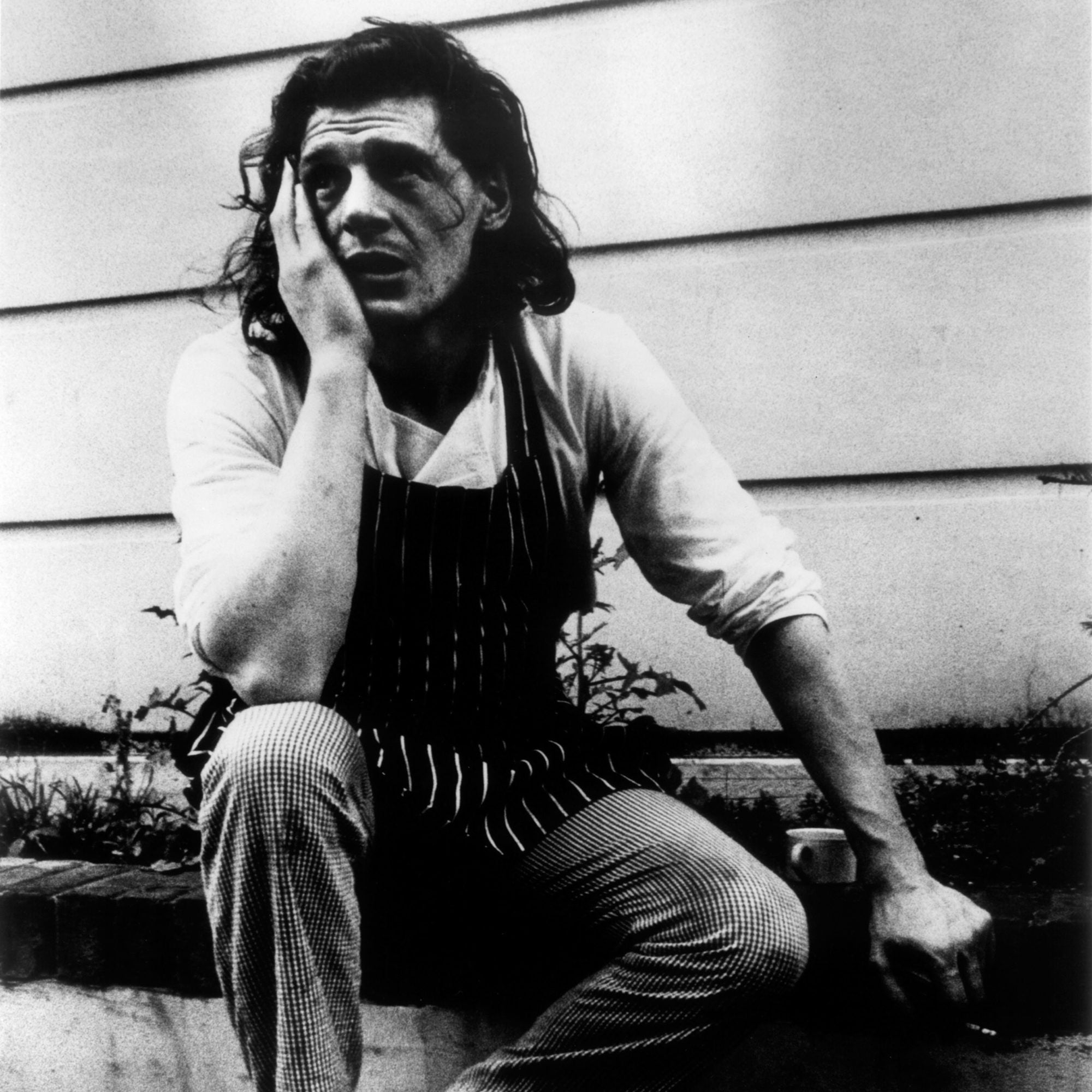

Was it a rock album or a cookbook? Was the smoldering cover character a chef or a front man? True, he wore kitchen whites, but a stringy mane flowed where his tidy toque should have been, and he faced defiantly away from the camera. And the title, which ran along the cover’s right side, was styled more like a punk seven-inch than Mastering the Art of French Cooking.

The year was 1990, and it was, of course, a book—British chef Marco Pierre White’s White Heat, a hybrid photo-journal and cookbook that revolutionized the public’s perception of chefs, chefs’ perceptions of themselves, and the notion of what a cookbook by a chef could be.

Chefs had been authoring books for centuries. Marie Antoine Carême and Auguste Escoffier were doing it in the 1800s and 1900s for an audience of fellow professionals. But the era when one might approach the cookbook department of an independent book shop or big-box chain store and lock eyes with a chef on a cover jacket was just dawning in the United States in the 1990s, stoked by a perfect storm of media coverage, a food-based cable network, and an eager pool of (mostly white and male) chefs who craved their 15 minutes of fame as much as they did a dining critic’s stars.

By the time chef-centric books by rising celebrities like Jean-Louis Palladin and Mark Miller entered the marketplace in the late 1980s, restaurant chieftains had been inching toward center stage for generations: In 1969, Fernand Point’s Ma Gastronomie (“My Food”)—based on his notebooks—shared his personal, some might say artistic, vision. Roughly a decade later, Great Chefs of France (1978), by Anthony Blake and Quentin Crewe, profiled all three-star-Michelin toques outside Paris, complete with food photographs, kitchen blueprints, and menus. And ascendant Americans such as Barry Wine of New York City’s four-star the Quilted Giraffe and Lydia Shire of Boston’s Seasons were immortalized in Cooking With the New American Chefs, Ellen Brown’s collection of portraits, profiles, and recipes, in 1985.

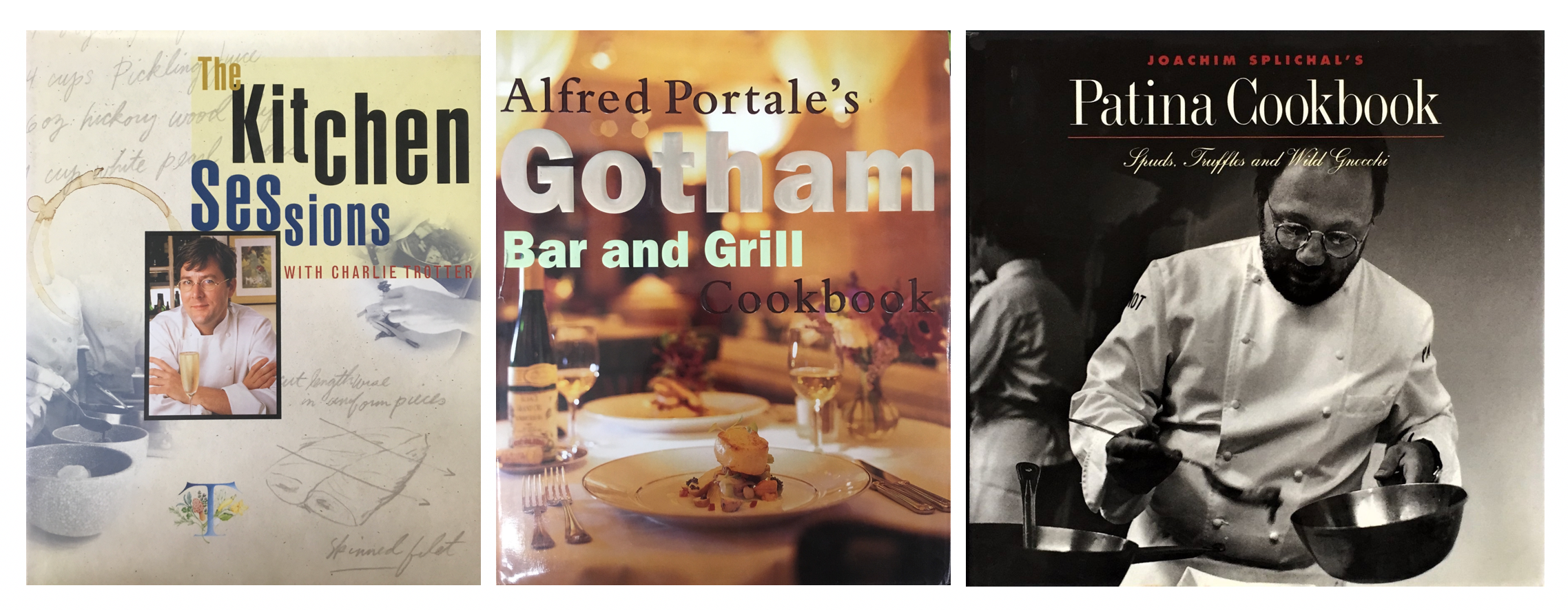

Charlie Trotter, Alfred Portale, and Joachim Splichal were key authors in the chef cookbook landscape of the ’90s.

In spite of these precedents, when American chefs began authoring cookbooks, most chose to model themselves after English-language food writers they’d come of age reading and learning from, like Julia Child, Elizabeth David, and Richard Olney—scribes who were themselves home cooks and whose writing conveyed a level of detail and nuance that was essential pre-YouTube.

In some cases, new chef-authors were also inspired by pioneering colleagues, such as Edna Lewis, who wrote two cookbooks in the 1970s. Books like Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook (published in 1982; the title itself recalls Olney’s French Menu Cookbook) and Florida chef Norman Van Aken’s Feast of Sunlight (1988) would be right at home on a shelf alongside books by those predecessors.

As chefs gained in prominence and became fixtures in splashy print ads, morning-show cooking demonstrations, and high-profile charity events, their publishing efforts gradually morphed into the supportive sheetrock of what came to be understood as a “chef cookbook.” The genre refers to monoliths celebrating chefs and their restaurants, with recipes meant to faithfully reproduce popular and innovative dishes first produced by a brigade of professional cooks who honed their preparation nightly, illustrated with lush photography and typically sold at a high price. An early release of this nature was Jeremiah Tower’s New American Classics (1986), which made repeated references to his flagship restaurant at the time, San Francisco’s Stars, and featured photo spreads depicting the chef picnicking and hunting.

A recipe for roasted cornish game hen with potato pavé from The Kitchen Sessions by Charlie Trotter

But the real big bang for the chef cookbook—the single title that changed the game forever—was White Heat. The volume, tall and lean like the chef himself, was as much about being a chef, in a restaurant, as it was about chronicling recipes. Readers were plunged into White’s restaurant galley (the book was shot at London’s Harveys in 1987), the medieval tumult captured in Bob Carlos Clarke’s black-and-white photography, which recalled the sinewy rock-and-roll photojournalism of Henry Diltz, Lynn Goldsmith, and Bob Gruen. The pages were filled with Marco-isms—little snippets that described the rigors of the kitchen life. (“A lot of people say I look like a rock star or designer punk. But I swear it’s the job that has carved my face.”) The book’s structure was revelatory at the time: Its first part depicts the raging bulls behind the fine-china shop; the second shows, in color, the exquisite food they prepared. An admiring Van Aken compares the effect to the shift from black-and-white to color in The Wizard of Oz.

“White Heat was a real shot in the arm to the idea that a chef was important as a personality,” says Matt Sartwell, managing partner of the culinary bookstore Kitchen Arts & Letters in New York City and a former (nonculinary) book editor. The book’s influence rippled across the Atlantic, stoking the self-esteem and ambitions of a growing population of American cooks and chefs.

“He looked like chefs I knew,” the late Anthony Bourdain—a knockabout New York City whisk at the time—told me in a 2014 interview. “He was the first chef who wasn’t a fat French guy. He was an English guy. Long, scraggly hair, rings under his eyes, gaunt cheeks, and he smoked in his fucking cookbook. And then you turn the page and there was this incredibly gorgeous food. Wow! That guy is capable of that? What does that mean for me?”

White Heat ushered in a decade’s worth of cookbooks in which the chef and/or their restaurant(s) shared center stage with the food; the closest variation was Joachim Splichal’s Patina—Spuds, Truffles, and Wild Gnocchi (1995), which depicted a day in the life of his Los Angeles restaurant with kitchen action in black-and-white, finished dishes in color.

“You may want to forget about the recipe specifics and use the photographs alone as your inspiration.”

If White tore down the wall between front and back of the house, Chicago’s Charlie Trotter made a no less influential commitment to faithfully re-creating upscale restaurant food on the printed page. The first of the late chef’s series of cookbooks for Ten Speed Press, simply titled Charlie Trotter’s, debuted in 1994, oversize, hefty, and featuring vivid close-up photography by Tim Turner, who framed the dishes as they’d be encountered in a restaurant, without the homey prop styling typical of cookbooks of the time. The recipes, such as Potato, Butternut Squash, and Black Truffle ‘Risotto’ with Foie Gras and Chicken Stock Reduction, were uncompromising; Trotter even sometimes called for ingredients from particular farms.

With White Heat and Charlie Trotter’s as North Stars, a number of commonalities proliferated in chef cookbooks of the era, in time almost becoming self-parody. There were vanity photographs of the chef; multiple, often-complicated sub-recipes; a call for professional equipment and ingredients that were impossible for a home cook to find. (These are not to be confused with books by the first crop of Television Food Network stars, which were pitched at a lower price point and marketed to a more mainstream audience.)

But was replicating those dishes at home ever really the chefs’ intention with their cookbooks? Were some of their editors to revisit those books now, they might feel like U.S. Customs agent Dave Kujan connecting Keyser Söze’s bulletin-board dots at the end of The Usual Suspects. The very first words of White’s introduction to White Heat are, “You’re buying White Heat because you want to cook well? Because you want to cook Michelin stars? Forget it. Save your money. Go buy a saucepan. You want ideas, inspiration, a bit of Marco? Then maybe you’ll get something out of this book.” And Trotter, in the opening pages of his first doorstopper, advised that “you may want to forget about the recipe specifics and use the photographs alone as your inspiration.”

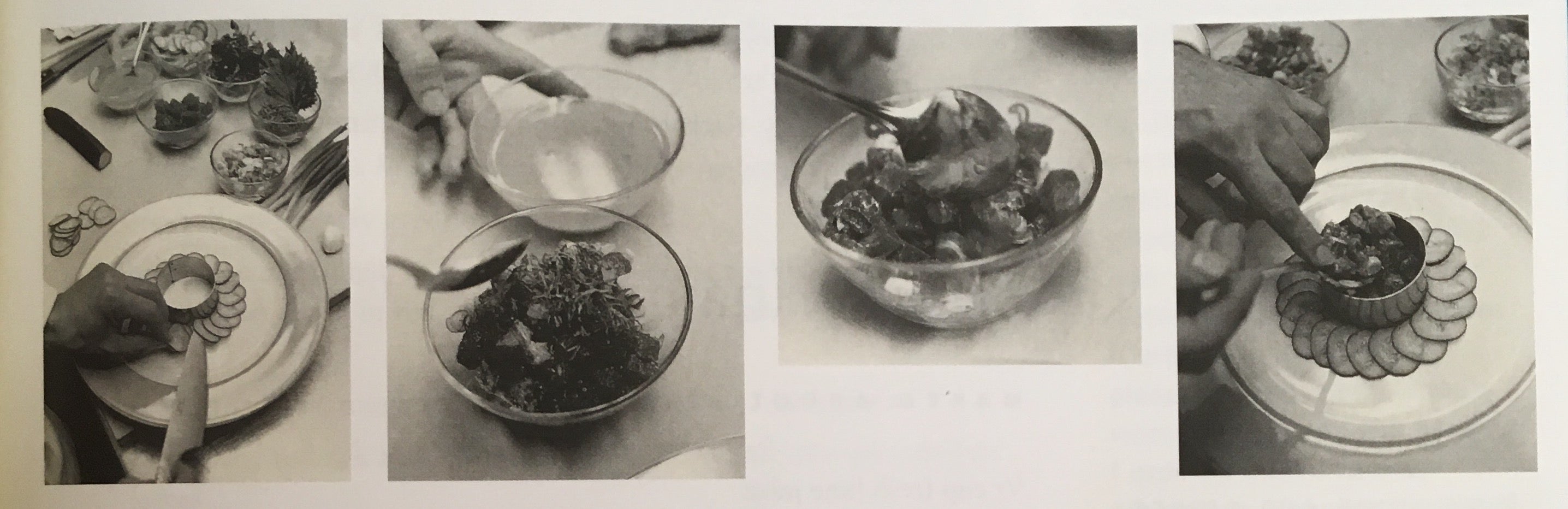

A tuna tartare recipe in Alfred Portale’s Gotham Bar and Grill provides instructions for “Everyday Presentation” for readers without ring molds at home.

The truth was that many chefs intended their books as souvenirs for their patrons or inspiration for their colleagues. Sartwell says that Trotter’s books are almost exclusively bought from his store by professional cooks, and Trotter’s close friend Norman Van Aken says that the chef was unbothered by whether or not readers hauled the books into the kitchen: “He wanted to share his passion; it didn’t matter to him if somebody went home and made a terrine of leeks.” Indeed, while the books might rarely have led to success at home, they retain a reverential place among professional cooks to this day. Bâtard’s Markus Glocker migrated from Europe to Chicago to work for Trotter because of his books, and Thomas Keller’s French Laundry Cookbook (1999) has had the same effect on generations of aspiring professionals, including former French Laundry chef de cuisine Timothy Hollingsworth.

Nonetheless, often-astronomical advances (sometimes in the low to mid six figures) created pressure for the books to perform in a manner commensurate with the chefs’ perceived celebrity. Stephen Rubin, president of Henry Holt, who in the 1990s was president and publisher of Doubleday Broadway, where he published chefs such as Alfred Portale (full disclosure: I was his collaborator) and Jean-Georges Vongerichten, believes that the decade represented a long, slow learning curve for the industry: “Just because you have a hugely successful cash-cow restaurant in Manhattan doesn’t translate into an ability to sell large numbers of cookbooks nationally,” he says.

“Those days are completely over; the ’90s were the times for those books,” says Rubin. He pauses, able to laugh after all these years: “And a time for publishers to lose money.”

Well, maybe not completely over. Many chefs publish cookbooks today, having accepted the prerequisite of bridging what they do in their restaurants with what the rest of us are capable of completing at home. But there are moments when lightning strikes, and a chef’s prominence, audience, and caliber almost demand an old-fashioned chef cookbook. These moments, however, are becoming much more rare.

Could it be that readers have also reached a saturation point? That the irresistible allure of going behind the swinging doors of restaurants has been replaced with the fatigue of too much access—not just in books, but also in competition shows like Top Chef and streaming biographies like Chef’s Table? And for those who were drawn to the “bad boy” element of some books … well, literal bad boys are divesting from their empires and retreating from public view.

In the meantime, a group of writers have reclaimed the cookbook space, combining the celebrity that first made chefs commodities with the accessible recipes we all want at home. Authors like Ina Garten, Chrissy Teigen, and Alison Roman now provide what Child, Olney, and David did before them, but they do it with quicker recipes for busier times—armed with television and social-media followings.

“I think Americans don’t want to spend that much time in the kitchen,” says Rubin. “Especially these days, but my guess is it was always that way. It just took a long time to realize that, at the end of the day, they want it simple.”