A ripe plum is rich and seductive, but also ornery. A dried plum is, well, the maligned prune. But plums have a passionate fan base, from Eastern Europe, Asia, and beyond.

As cookies go, triangular hamantaschen are generally terrible. But they’re a hell of a ritual.

The Purim story in the Book of Esther, in a nutshell: Mordecai, an adviser to the Persian king, insults a new viceroy named Haman by refusing to bow in obedience. Upon learning Mordecai is Jewish, the incensed Haman decides to kill not just him, but all the Jews in the kingdom. Mordecai discovers this plot and assists his niece Esther, the king’s bride and hero of the story, in thwarting the genocide. As recompense, Esther convinces the king to arm his Jewish subjects so they may slaughter his sons and soldiers. And Haman? She gets him hanged.

Today, Jews celebrate this victory by drinking, partying, and eating hamantaschen to spite the man who’d have us dead. In Hebrew, the cookies are called ozney Haman—Haman’s ears.

Modern hamantaschen are filled with everything from raspberry jam to chocolate, but I only have eyes for those with a nugget of lekvar in the center. A preserve made from cooked-down prunes whipped into a paste, lekvar is dense and chewy like caramel. My grandparents spread it on their morning toast and smeared it into buttery tarts; as a kid, my mother skipped the filler and ate it directly off the spoon.

Lekvar is just one of the many ways that plums fall into the Eastern European Jewish kitchen. We also stew the fresh fruit into sauces for dessert, or into braising liquid for brisket. And from our goyishe friends and neighbors we learned to bake plums into dumplings, cakes, and tortes—relishing the twangy, almost electrifying effect their tannic skins have on the tongue.

Like my ancestors, the Prunus genus of flowering plants, which includes plums and all other stone fruits, was born around Eastern Europe. And like the Jews, the plum is itinerant; dozens of varieties have laid down roots from Korea to California.

Here is the thing about plums: You can pick them in every color of the rainbow, but no matter the kind, they are a challenging fruit. A ripe plum is rich and seductive, but also ornery. Sweet, to be sure, but with an acidic spark and an astringent bite. Peaches are puppy dogs—sugary and desperate for your love. By contrast, plums are goats that won’t stop chewing on your clothes. They’re complicated fruits that take work to understand and must be appreciated on their own terms.

In synagogues and around the table, Jews learn from a young age that sweetness comes at a price: sacrifice in adversity, remembrance of the past, education for the future. Which is why I consider the plum to be a quintessentially Jewish fruit, a reminder that sweet tastes don’t come easily. But every culture learns this from the plum, one way or the other.

Technically, Prunus mume—the feisty, bracingly tart plum of China and Japan—is closer to apricots than other plums. But it’s called a plum by pretty much everyone and shares the brooding personality of its P. domestica relatives. Japanese cooks tend to salt-cure it into a piquant pickle called umeboshi, but in China, there’s wu mei, an intensely smoky and savory prune that’s at once snack, cooking ingredient, and medicine.

You can find wu mei—black and shriveled, redolent of smoldering coals—in the dry goods section of Chinese groceries and herbalist shops. And if you’re really lucky, you’ll happen on a concentrated syrup of wu mei with osmanthus, hawthorn berry, licorice, and rock sugar, made for diluting with water into suanmeitang, a cooling, salty-sweet drink served like lemonade in China and Taiwan.

Jonathan Wu, the chef of Nom Wah Tu in New York, grew up eating sour salted plums coated in licorice powder as a snack and is drawn to the Chinese plum as a source of acidity in his cooking. But his big obsession is that concentrate. “It’s like barbecue sauce,” he says in an almost conspiratorial whisper. He mixes it with hoisin, rice vinegar, and soy sauce to braise lamb until it collapses, then piles the meat over wheat noodles, which he tops with fried pickled peanuts and loads of dill. It tastes the way I always wished my grandmother’s brisket could and summons the full power of the plum: warm and familiar yet explosively multifaceted, tinged with an antediluvian darkness.

For Wu, that smoky languor is what makes wu mei taste so good. He’s not the only one who thinks so. In Szydłów, a Polish village known for exceptional plums, smoked prunes are a local delicacy, crazy good when roasted within the body of a duck or goose. And across the Atlantic, Sioux chef, educator, and cookbook author Sean Sherman has some turn-of-the-century photos of folks drying plums and other fruits by a smoldering log. “A ton of smoke flavor is going into the fruit that way,” he explains.

In plum-growing regions, Native American cooks pounded prunes into pemmican—an ancient power bar of dried fruit, nuts, and animal fat. Sherman adds prunes to the dough of toasted wild rice flatbreads, and even grinds fully dehydrated plums into a powder to use as a seasoning and flour.

Sherman’s a fan of the indigenous P. Americana that grows on Minnesota’s Red Lake Reservation, but for my money the greatest plums on the continent come from Frog Hollow Farm in Brentwood, California, where Rebecca Courchesne and her husband, Al, grow a dozen-odd plums and plum-apricot hybrids. Their Santa Rosas, a native Californian variety developed by Luther Burbank in the early 1900s, are intensely sweet with moody undertones of earth and spice, but with skins tart enough to snap your eyes and heart to attention.

“I would never skin a plum,” Rebecca Courchesne tells me. “The skin is part and parcel of the fruit. But home cooks underestimate how bitter and aggressive it can be.” As the farm’s chef, she’s learned to pay plums their due respect. Instead of blasting them with sugar, which would cause their watery flesh to weep liquid everywhere, she uses plums to add verve to other fruits, such as blueberries for conserve and nectarines for galettes.

We learn to appreciate plums in our own ways, but the ancient fruit’s greatest lesson is the necessity of reinvention. A raw plum is best transformed into something else, and it in turn transforms us. “The plum is one fruit better cooked than raw,” says Marian Burros, whose plum torte recipe was famously published every September in The New York Times from 1983 to 1989, to mark the start of Italian plum season. “And that dish is part of my DNA.” To make the classic German dessert, you nestle plum halves into a simple cake batter, then bake until the torte rises around the plums, which soften into jam.

“Better to think of [plums] in their more decadent old-world iterations,” Anca L. Szilágyi writes in a cultural and personal history of the fruit. “Dumplings, jam, brandy—the sort of products that elicit both rabble-rousing and decorous ritual.”

Szilágyi’s family came to the U.S. from Romania. Mine is mostly from Poland. And despite the plum’s many colors and varieties and global instantiations, I’m still convinced that our ancestors understood it best. They’re the ones who baked hamantaschen, and who drank plum brandy to soothe their souls. Often called slivovitz, the potent fire water is the purest expression of the plum, with the most vivid sense of place.

Slivovitz tastes best when poured from a plastic bottle by a hairy-armed guy who distilled his own in a shed. It should be a touch sweet but not sugary, expansive in the throat and warming in the belly, and vicious in its bite, both toxin and curative.

“Into her suitcase it went,” Szilágyi recalls of her grandmother restocking her supply on a trip to the Old Country, “carefully transported back to the States so that it might properly ‘disinfect’ us before each dinner.”

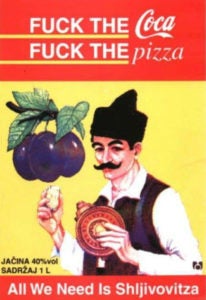

Back in the Balkans, plums and plum brandy remained a vital marker of identity. In the early 2000s, an enclave of Serbs in the city of Mitrovica rankled under a looming American presence following the Kosovo War. A slogan of resistance arose, in defiant English for all to hear, and it was soon printed with artwork on postcards, flyers, and T-shirts.

In the painted illustration, a mustachioed man in a traditional cap stands beneath a bundle of plums on the tree. In one hand, he holds a circular bottle of plum brandy. In the other he grasps a glass filled to the brim. “Fuck the Coca, fuck the pizza,” the slogan reads. “All we need is šljivovica.”