In San Antonio, a cookbook collection has plenty to tell us about a fascinating, complex, and frequently misunderstood cuisine.

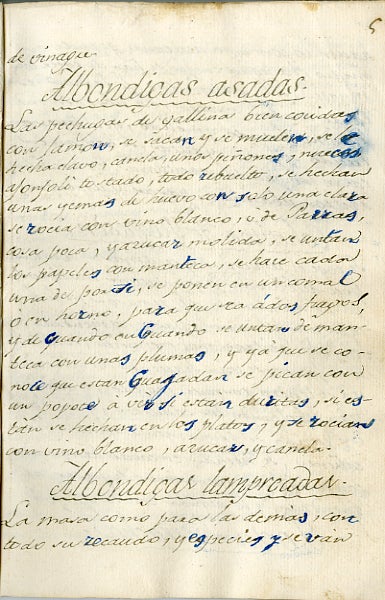

Every Mexican cook I know, including my mother, has a recipe for albondigas—meatballs, which are usually, depending on the cook, either served as a soup or something closer to a meat main dish drenched in a thick sauce. None I’d ever come across resembled those of Doña Maria Ramona Quixano y Contreras, who in 1808 wrote a Spanish-language cookbook of stews, fruit pastes, and desserts in Silao, Guanajuato.

The Mexican meatballs I know are delicious but mundane—a mix of pork or beef, salt, pepper, maybe cumin or oregano, perhaps a bit of hard-boiled egg or rice inside. Doña Maria’s meatballs were baroque, upscale, multi-step creations, bathed in wine and sugar.

“Cook hen breasts well with ham,” she writes in elegant, slanted cursive. “[T]ake them out and grind them, add clove, cinnamon, a few pine nuts, pecans, toasted sesame seeds….” Add a few egg yolks and just one egg white, she continues, then sprinkle the mixture with a bit of white wine and sugar.

To check if the chicken is done, Doña Maria advises piercing the meat to check for firmness. That advice, translated into Spanish, with its familiar diminutive—Se pican con un popote, a ver si están duritas—sounds like it could still be uttered today by Mexican tías everywhere. To finish the dish, she suggests sprinkling the meatballs with more white wine, sugar, and cinnamon.

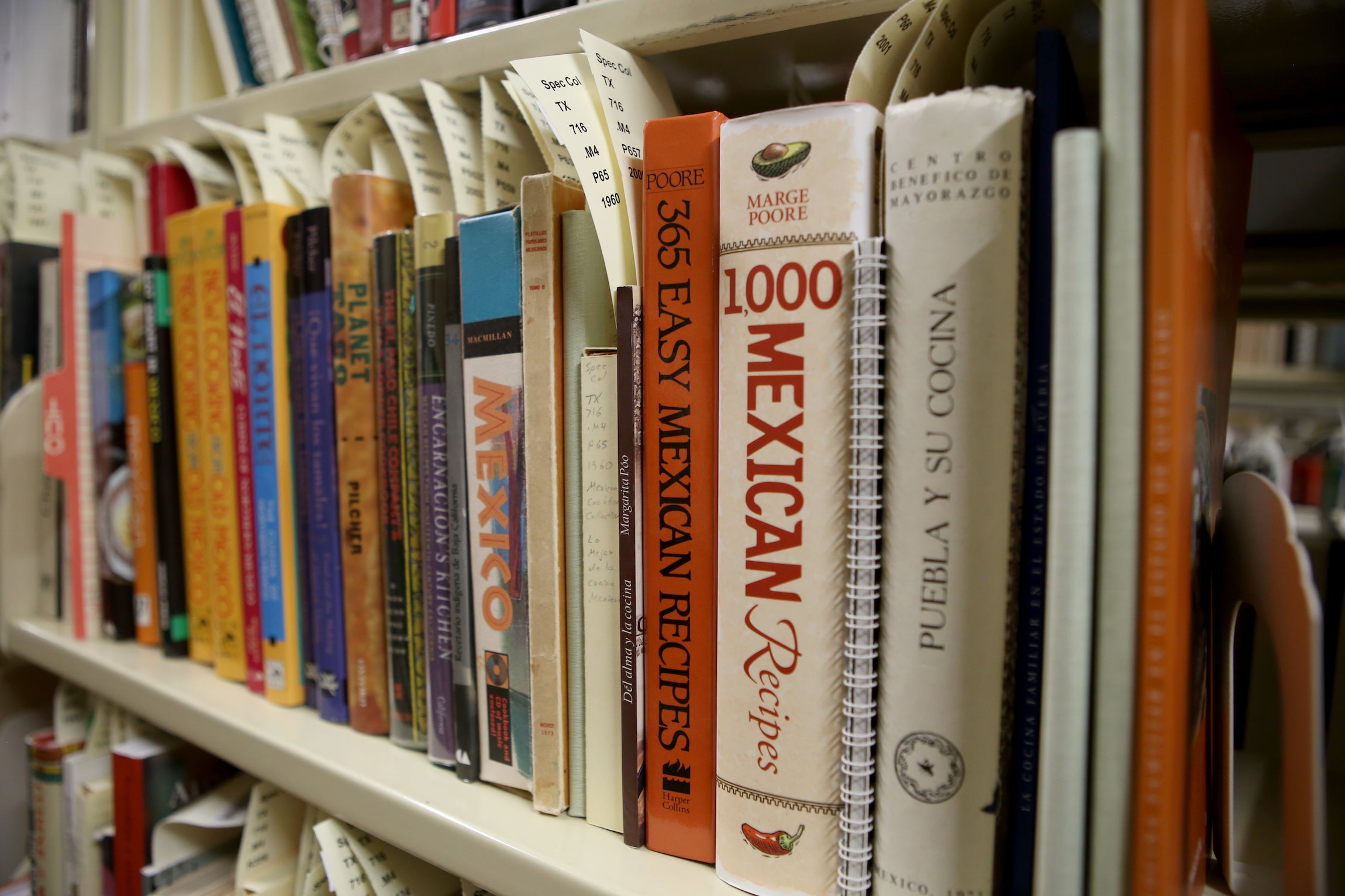

At nearly 1,800 titles and growing, the UT San Antonio collection of Mexican cookbooks is one of a kind.

Doña Maria’s recipe book, its hand-lettered cover intact, sits behind a thick paper shield at the University of Texas at San Antonio, part of the Mexican Cookbook Collection within the UTSA Libraries Special Collections. At nearly 1,800 titles and growing, the collection is the only one of its kind in the United States, devoted specifically to Mexican cooking on both sides of the border. (About 70 percent of the books are in Spanish; the rest are in English.) Other libraries collect cookbooks for research purposes; the Schlesinger Library at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard is perhaps the largest and best known, with more than 20,000 cookbooks and food-related titles. San Antonio’s collection is unlike the others in that it’s dedicated solely to Mexican cooking and its vast interpretations.

The collection began in 2001 with a donation of 550 books from San Antonio resident Laurie Gruenbeck, a public librarian who had collected Mexican cookbooks while traveling through Mexico and the Southwest. When the books started spilling into her bedroom, recalled former UTSA rare-books librarian Juli McLoone, Gruenbeck thought it was time to find them a new home. Although the collection originally carried Gruenbeck’s name, McLoone says, Gruenbeck suggested they change it, worried that a German woman’s name would not seem welcoming to Mexican-American families who wanted to donate books.

The books live in a temperature-controlled vault on the fourth floor of UTSA’s John Peace Library, a hulking structure on the main campus about 30 minutes from downtown. The Special Collections Reading Room, adjacent to the vault, is a small, plain, and startlingly quiet space (even for library standards), with a handful of caramel-colored wooden tables and chairs.

A recipe for albondigas from an 1808 book by Doña Maria Ramona Quixano y Contreras

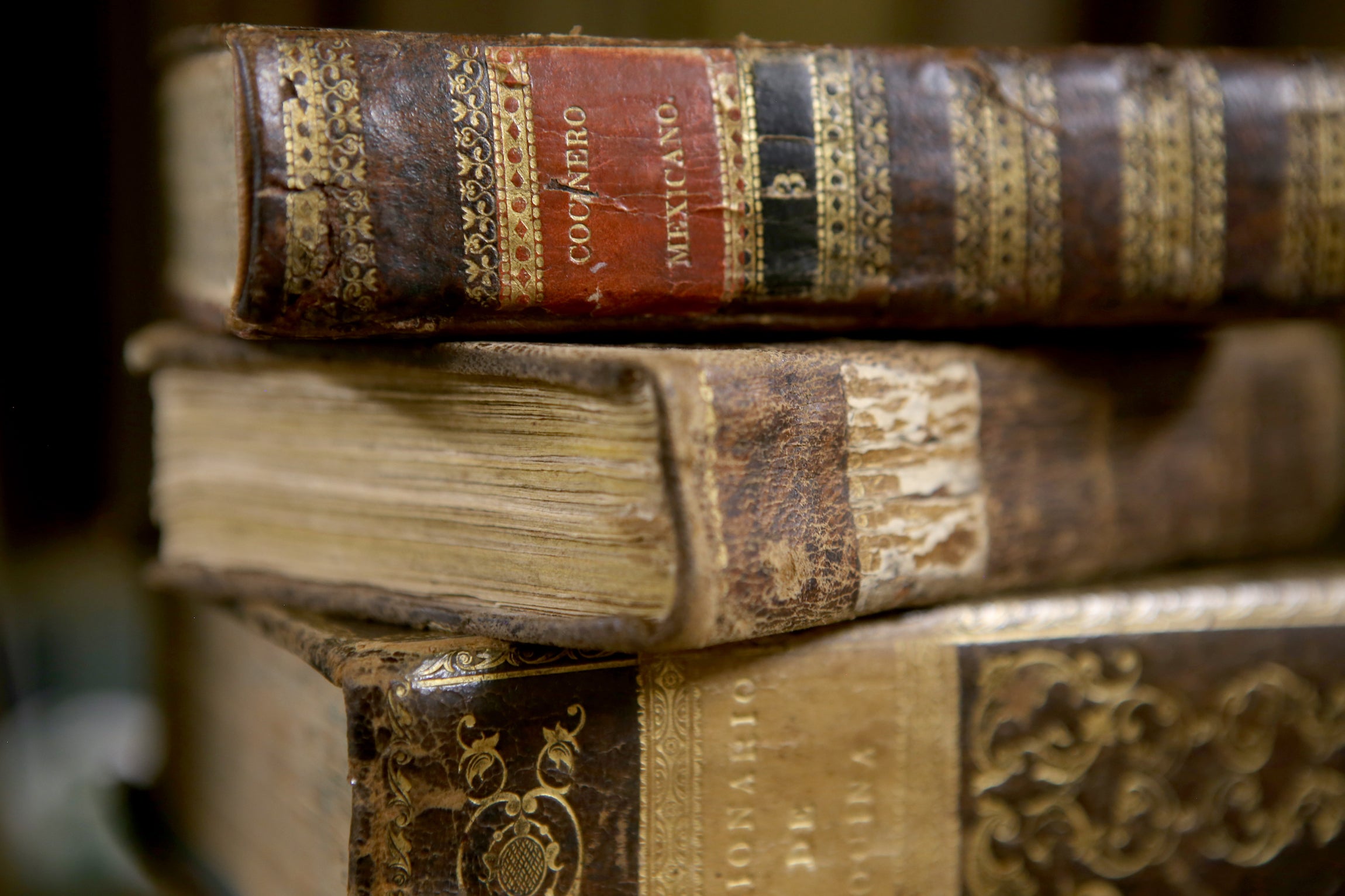

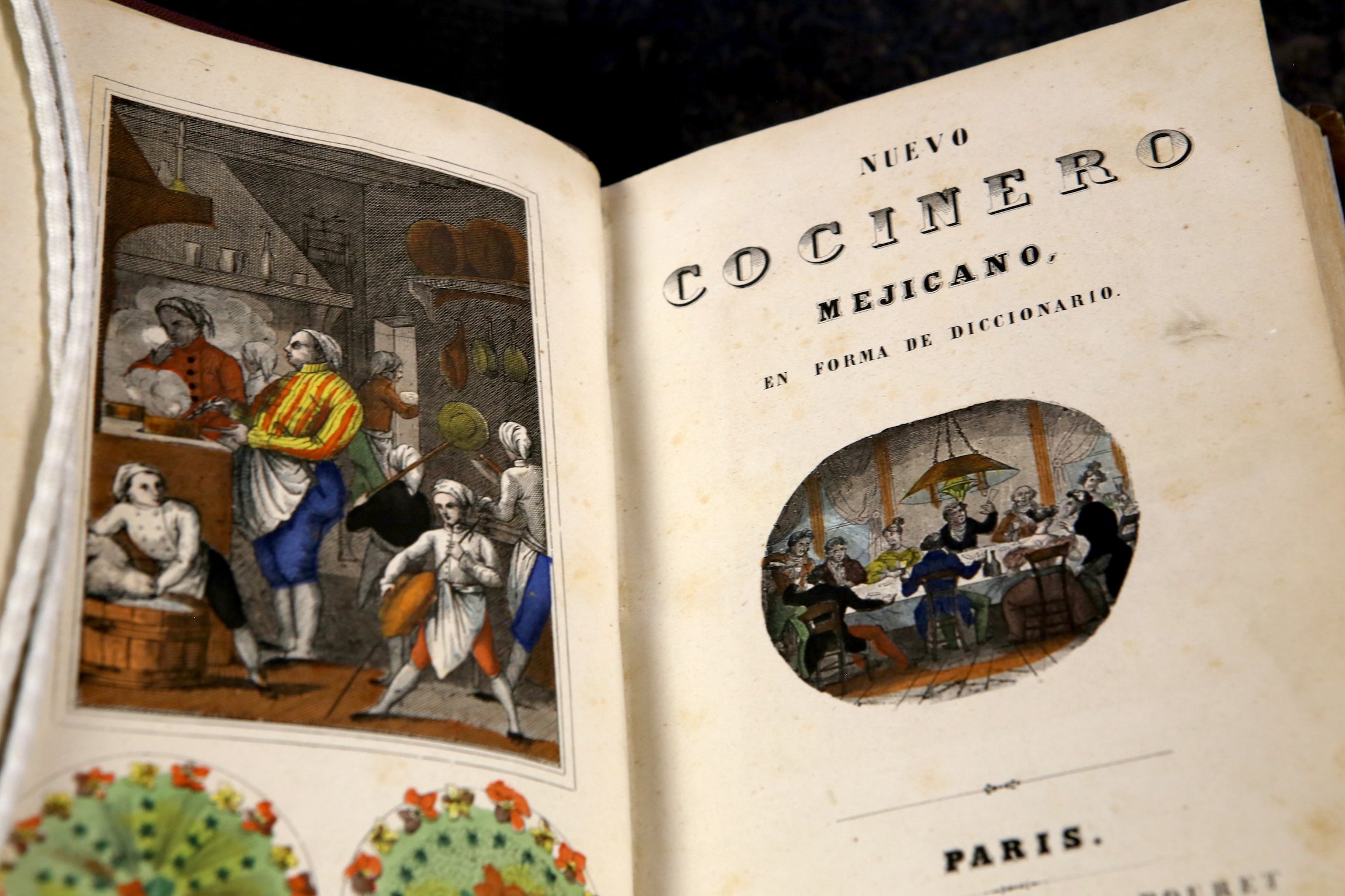

For Mexican-food nerds like me, visiting the reading room can feel like making a pilgrimage to a church. It is open to the public on Monday through Wednesday and at other times by appointment, so anyone has access to a 1831 edition of El Cocinero Mexicano, considered the most important cookbook of 19th century Mexico, and can read that a quesadilla de prisa (“quesadilla in a hurry”) comprised a corn tortilla filled with cheese—aged, fresh, or goat’s—and then slathered in browned lard and given a pinch of salt. While flipping through a 1910 school lesson book pasted with yellowed recipe clippings, I learned that a capirotada (always a bread pudding, or so I assumed) could also comprise layers of cooked Mexican squash interspersed with cheese and butter.

Thumbing through the nearly 30 Mexican cookbooks I requested on a recent visit, I also felt a range of emotions I didn’t expect: surprise, anger, sadness, pride. I’m a Mexican-American cookbook author and have studied traditional Mexican cuisine in Mexico, but the contents of these books gave me a rush, like I was watching a movie that no one had seen before.

I live in Los Angeles and traveled to San Antonio just to see this collection. Over the course of my three days there, I marveled over the Spanish-influenced plates of Doña Maria’s era. I felt the burst of nationalism that came with Mexican Independence and the embrace of native ingredients such as corn, beans, and chiles. One particularly intriguing recipe in El Cocinero Mexicano for a Torta de Nada (“Nothing Cake”) called for blending chile ancho, cumin seeds, garlic, and day-old bread—and cooking the mixture with beaten eggs.

I imagined the bustling banquet halls of the upper-crust Porfirian era, which glorified European and French cooking, while flipping through El Cocinero Práctico, published in 1892 in Madrid and Mexico. One section featured pages of drawings of “important” kitchen equipment, including a mustard pot and spoon, a coffee bean toaster, a rectangular pan for making the Spanish leche frita dessert, and a salad bowl. Not listed, interestingly, were native Mexican cooking utensils such as clay pots, a metate, and a comal. I watched, in my head, as the housewives near the era of the Mexican Revolution sat at their writing desks and composed the recipes that they might make for their families.

And then I got to the American cookbooks.

With these early-20th-century cookbooks, I expected to find dumbed-down recipes and stereotypes—the lazy Mexican sleeping under the cactus, the sexy señorita in the low-cut dress, perhaps the first recipe for the taco salad bowl. Some of that was found in the collection. But a surprising number of books took the cuisine seriously, earnestly explaining what Mexican cooking was like in Mexico. This was decades before Diana Kennedy, the British author widely credited with helping Americans understand regional Mexican cooking—or Rick Bayless, the Chicago chef who has dedicated his career to interpreting traditional Mexican cooking for U.S. audiences. This meant that writers had been trying to encapsulate Mexican cooking for mainstream Americans for at least 75 years already, and yet the myth that Mexican food means only nachos and burritos and enchiladas persists today. Is no one listening, or is the process just that slow?

For more than six hours each day for three days, I felt like I was being pulled in two directions as I read—one direction recognized that Mexican cooking had a unique, rich legacy, and I felt proud that it formed part of my heritage. The other felt sad and mad that among the American cookbooks, Mexican-American voices were overwhelmingly missing. Mexicans love to argue that there is only one “real” Mexican cuisine, pointing to the specific style of regional cooking their grandmothers made, or the food they ate growing up. UTSA’s collection shows that what both Mexicans and Americans know about Mexican food is actually just a partial story; the real one is full of gaps and emotional contrasts, and a lot of it hasn’t even been written yet.

In the reading room’s spare environs, it’s possible to see the first mainstream narratives of Tex-Mex and Mexican cooking beginning to take shape.

Adán Medrano, a food writer and chef in Houston, says that in Texas, Mexican-Americans have purposely been excluded from the dominant narrative that developed around Mexican cooking.

“Mexican-Americans were second-class citizens and were, for example, by the reason of the poll tax, excluded from voting—we could not have economic or political power,” explains Medrano, who has written two cookbooks on what he calls Texas Mexican cuisine, or the homestyle cooking that he says falls outside the realm of Tex-Mex. “Many of the influences that affected our food, like chiles [and] beans, were stereotyped and became bad things.”

In the reading room’s spare environs, it’s possible to see the first mainstream narratives of Tex-Mex and Mexican cooking beginning to take shape—among the books I pulled, that story was told almost exclusively by white people, starting with Gebhardt Chili Powder Co.’s Mexican Cooking. The book, first published in 1908 and sold for 15 cents, promises to deliver “that real Mexican tang” and assures readers that Gebhardt products are “clean,” “wholesome,” and hygienic. It includes recipes for both American and Mexican chili con carne.

Discovering Mexican Cooking, published in 1958 by San Antonio’s the Naylor Company, begins with an introductory Q&A between the white female author, the white female illustrator, and a third Mexican woman “advisor” tasked with making sure the book’s recipes were authentic. (A photo shows the Mexican woman serving the smiling white ladies.) The author, Alice Erie Young, peppers the advisor, Theodosia Moreno Samano, with questions like “Do the Mexicans use any spice but chile?” and “If tortillas are so popular, don’t they know about wheat bread?” Samano answers patiently, but I pictured her inwardly rolling her eyes.

Those books made the Mexican-American voices in the collection seem all that more important. Ella T. López, the La Puente, California–based author of 1976’s Make Mine Menudo: Chicano Cook Book, documents the kind of tomato- and meat-based Mexican-American cooking I grew up eating and haven’t seen written in a cookbook anywhere, ever. (When I found a recipe for torn tortillas scrambled with eggs, one of the main meals of my childhood, I excitedly texted my mom.) Or Lucy Garza, whose 1982 South Texas Mexican Cookbook is a mix of recipes, stories, and even Spanish-language nursery rhymes dedicated to the food Garza’s family ate in the Rio Grande Valley.

To read these books, visitors must place them on foam wedges to avoid disturbing their spines. Weighted shoelaces called snakes keep fragile pages from turning. White gloves are not required for the older books, so you can still touch the paper and feel the ink that the original writer penned. It’s almost like the ghost of the cookbook author is sitting next to you, talking.

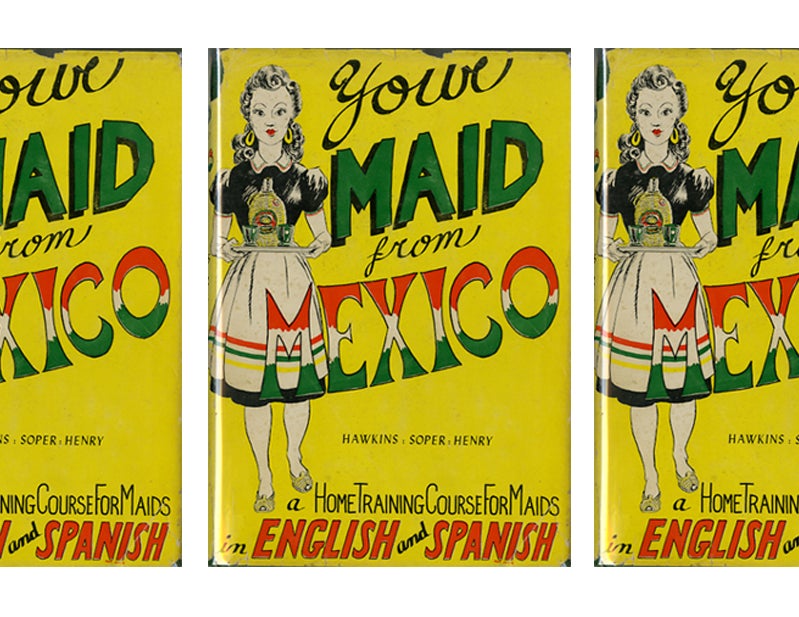

It’s not always a comfortable feeling, particularly with cookbooks that would now be considered racist or sexist. One affecting book, Your Maid From Mexico, also published by the Naylor Company in 1959, discusses how to train one’s Mexican domestic worker and includes a section on menu ideas. In the book, the female authors stress the importance of the maid brushing her teeth, wearing deodorant, and changing her sanitary napkins. The authors write in the introduction: “Since many of our maids come from homes devoid of gas, electricity, or water, it must indeed be breathtaking to be plunged into the well of disposals, vacuums, blenders, etc., without a premonitory word.” It’s a reminder that even in San Antonio, a city that is now predominantly Mexican-American, the racism runs deep.

The collection, in all its complexity, has been a boon to chefs and cookbook authors. Rico Torres, one of Food & Wine’s best new chefs of 2017 and the owner of high-end San Antonio Mexican restaurant Mixtli, says he’s visited the library often, particularly when he’s stuck in a creative rut. Mixtli’s tasting menu changes every 45 days and focuses on different regions and historical themes of Mexico. Torres has called the library his “secret weapon” for menu development: Some of the dishes that the library has influenced include a zacahuil, or giant tamal traditional to Mexico’s Huasteca region, and a dish Torres called “lluvia,” or rain, which included garbanzo, pickled chayote, purslane, and pipián, topped with cricket ash.

“I don’t want to make the same recipe that my great-grandma would have been cooking, but I want to keep those ideals, the flavors, and the identity that that dish has,” Torres explains. “These books offer an amazing foundation of that, as well as being truly inspiring. You go in there wanting to cook everything when you come back out.”

Tex-Mex cookbook author and Homesick Texan blogger Lisa Fain says the library was a great resource in helping her trace early chile con queso recipes in Mexico. She remembers thumbing gingerly through a 19th century Mexican cookbook when she found a recipe for “chiles poblano,” a dish that featured chiles and cheese. It was chile con queso except for the name, she said, and it was exactly what she’d been looking for. “I think I yelped,” says Fain, whose new book is Queso!: Regional Recipes for the World’s Favorite Chile-Cheese Dip. “When you find that needle in the haystack, you’re so happy.” UTSA has tried to connect its books to the wider community, partnering with local chefs and organizations to showcase recipes from the collection. In May the library hosted Ven a Comer, a multiday event featuring a dinner made by Torres, two chefs from Mexico, and two other chefs from San Antonio. A similar event is planned for June.

Agnieszka Czeblakow, the rare-books librarian who oversees the Mexican Cookbook Collection, says new books come in all the time, either through purchases she makes from collectors or through donations. She describes the collection as one of the university’s “active collecting priorities.” Czeblakow has watched plenty of chefs become “kind of overwhelmed” when they start reading. “There was one chef who was texting his sous chef as he was reading the ingredients: ‘Can we get this? Can we get this?’” she says. “Their minds are blown by what they’re seeing.”