The Atomic Age Jewish cookbook Love and Knishes was written in a voice so skeptical, so long-suffering, so unapologetically, unfashionably Jewish that you could only imagine its author, Sara Kasdan, as an old woman living on the fifth floor of a Lower East Side tenement. But that was far from Sara Kasdan’s story.

I can’t remember where I found my copy of Love and Knishes—I’m pretty sure it was a yard sale, but I’m also pretty sure it was a secondhand bookshop. What I do remember with absolute clarity is this: I had never seen any cookbook like it. This was sometime in 2011 or 2012, and I was used to cookbooks that were impeccably styled, frequently self-serious, entirely pun-averse, and, above all, demanding of admiration.

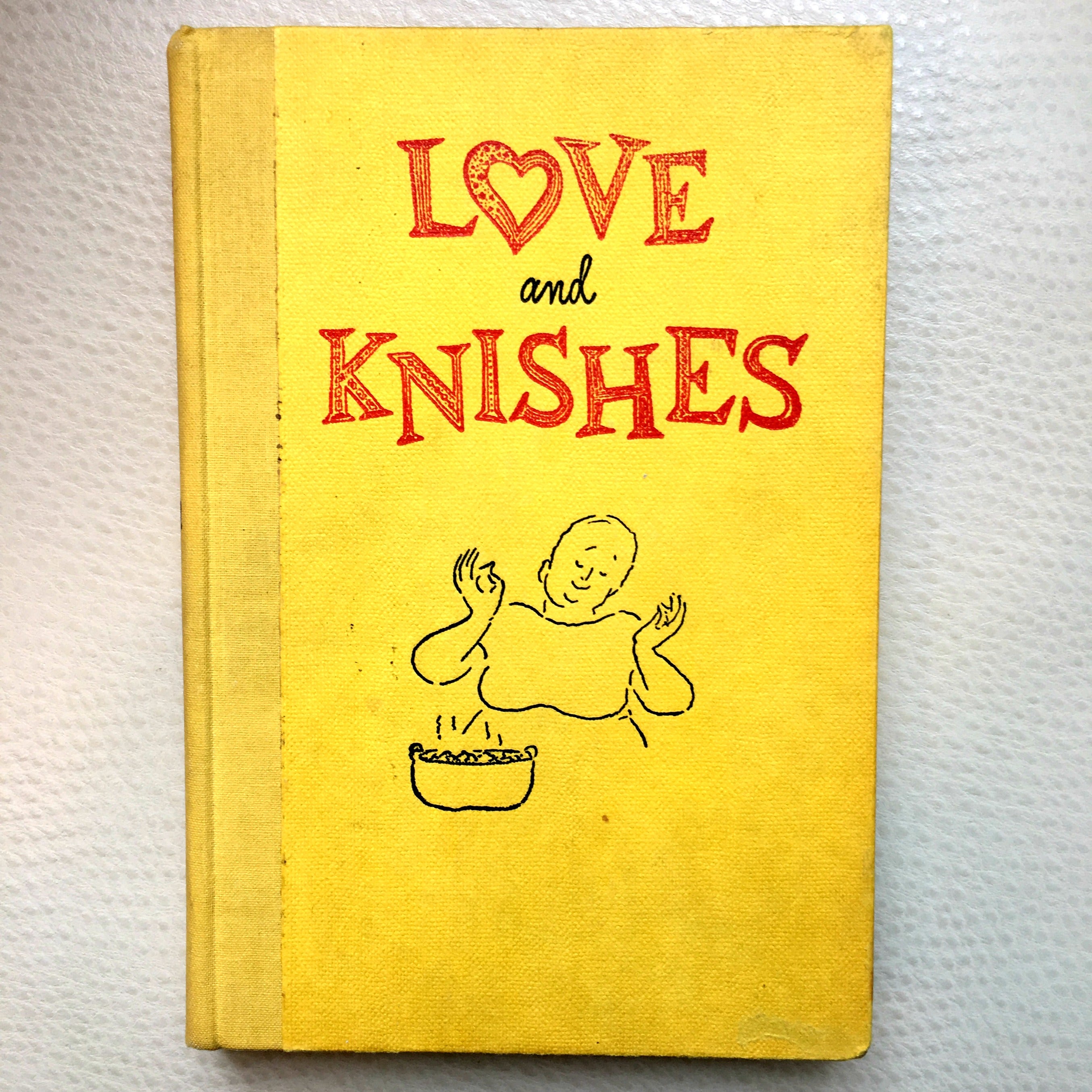

This book refused all of these descriptions. It was plain, its mustard-yellow cover illustrated only by a spindly line drawing of a woman who could most accurately be described as “bosomy,” smiling over a pot with steam rising from it. I’d later learn that its illustrator, Louis Slobodkin, was best known for illustrating numerous children’s books, including James Thurber’s Many Moons. But at the time I was just struck by the whimsy, and by the book’s title. Love and Knishes: I smelled the Borscht Belt.

Opening the book, the scent grew stronger. The copyright page told me I was holding a 1957 fifth printing, copyright 1956 by a woman named Sara Kasdan. Everything that followed told me I had a piece of history in my hands. There was a glossary that defined lox as “a partner to bagels” and a mitzvah as “a good deed, like taking the cook out to dinner once in awhile”—and advised that shortening could be substituted for schmaltz “just as a muskrat coat may be substituted for a mink.”

There were chapter titles like “Oodles of Noodles, or My War with Lokchen,” “Put Some Schmaltz in It,” and “You Can Be Normal, Too, Why Not? (Breads and Rolls).” A chapter about vegetables (titled “Education Is a Wonderful Thing”) was thick with beets, cabbage, potatoes, and sauerkraut, and prefaced by an introduction that talked not about vegetables but about the newfangled nutritional advice to feed children vitamins. “Was a time when meat and potatoes was enough,” it lamented. “You gave the baby a good hard bagel to teethe on….” A rant about psychology (“Everybody has complexes—a new word. In my day, we didn’t know from complexes”) introduced the bread chapter.

I found one recipe that called for nine feet of beef casings, another for chopped liver strawberries that “are very pretty around a green jellied salad,” and a recipe for cholent (defined as “any food that has the stamina to withstand 24 hours of cooking”) that required one cup of schmaltz. (Schmaltz itself was described, rather lyrically, as “a golden richness, a bubbling warmth, a loving tenderness, a promise of good things to come.”) I found five different recipes for herring, and one for sweet-and-sour fish that called for gingersnaps. And I found, illustrating a chapter called “So Why Should You Kill Yourself? Or Short Cuts,” a drawing of a cook holding a loaded gun to her head.

I had, in other words, found gold. This was the Ur-bubbe text, written in a voice so skeptical, so long-suffering, so unapologetically, unfashionably Ashkenazi Jewish that I could only imagine Sara Kasdan as an old woman living on the fifth floor of a Lower East Side tenement, poking her head out of the window just long enough for Jacob Riis to take her picture. This was a voice from the shtetl, suspicious of the modern world but also oddly prophetic; one passage, from the three-recipe Salads chapter, notes that “nowadays as soon as an infant learns to talk it knows already from allergies. So now instead of saying, ‘I hate spinach,’ they tell you, ‘So sorry, but I’m allergic to it.’”

At the time I stumbled across Love and Knishes, the food world was deep into a Jewish culinary revival—though maybe “gut renovation” is a better term. The Gefilteria had arrived to champion the cause of better gefilte fish, new-wave delis from Boulder to Brooklyn trafficked in grass-fed pastrami and vegan reubens, and cookbook authors and professional chefs were dispatching ingredients like tahini, labneh, and vegetables other than potatoes to illustrate the breadth and complexity of Jewish cooking.

I loved all of this, this Jewveau cuisine with its worldly wardrobe and sudden, disorienting interest in seasonality. But I loved Love and Knishes because it was none of these things. If anything, it’s what this new generation was rebelling against: the 50 shades of beige, the death by schmaltz, the aversion to roughage (seriously: even iceberg lettuce fears to tread in the Salads chapter). To look at the book superficially is to see only kitsch and pints of sour cream, and to register the kind of can-you-believe-people-ate-that-way reflex that greets many Atomic Age cookbooks, with their wondrous Jell-O molds and terrifying casseroles.

When I looked more closely, I began to see other things. For one, the book was mottled with decades-old grease stains and annotated with penciled-in notes. Something brown had violently splattered the Passover Date Torte recipe, next to which someone had written “good.” Clearly, the book had been in frequent rotation, suggesting its recipes were trustworthy. Certainly, they were comprehensive and uncompromising: You don’t include recipes for oophilaifers, essig flaish, or a gahntze tzimmes if you’re trying to win points for assimilation. You also don’t make all of your recipes kosher. As I read, I realized that this is a book that is, above all, about balancing acts: It reads as convincingly as a work of scholarly passion as it does as an extended stand-up routine.

And then there was that voice, the bubbe perplexed and confused by the modern world. The more I read, the more I realized that this was the voice of a Southern Jew, one who apparently lived in a Louisville ranch house and dedicated her work to “all the wonderful women who never cooked from a book.” The name Sara Kasdan meant nothing to me, but her writing suggested that, beneath the book’s Yoda-like Yinglish syntax (“one day it comes to me the idea to write a Jewish cookbook…”), there lurked someone who was in on the joke—and also understood the import of translating untested, unmeasured dishes into a compendium of legitimate recipes geared toward not just Jews, but everyone.

“Jewish food is good food, so why shouldn’t everybody like to eat it even if he is not Jewish? Besides, from eating other people’s food you are learning about them and it is bringing you closer together,” Kasdan wrote. “[I]f you are not Jewish this book will bring you pleasure, I hope. Because this is my intention.” While Kasdan was far from the first to formalize Jewish recipes with the goal of finding a wide—and not necessarily Jewish—audience, I was moved by the poignancy underpinning her statement of intent, and her quiet appeal for unity though food. It was simple, eloquent, and even, you could argue, ahead of its time; it complicated my notion of Kasdan as a bubbe in search of a punch line.

So I decided to go looking for her.

Initially, the Internet failed to provide an answer. Love and Knishes’ publisher, the Vanguard Press, was long defunct. Googling “Sara Kasdan” turned up Love and Knishes’ Amazon page but little else, not even a Wikipedia entry. But searching for her obituary turned up findagrave.com (really), which showed me a photo of a headstone for a Sara Moskowitz Kasdan in a Louisville Jewish cemetery. Born on Valentine’s Day in 1911, she had died in 1999 at the age of 88. Her husband, James, and a daughter, Harriet, were also listed as deceased. Googling further, I found an abstract of a 1969 Louisville Courier-Journal article about Sara Kasdan and her new book, Mazel Tov, Y’All; it mentioned that she had been born in Fort Smith, Arkansas. At that point, I gave in and signed up for a free trial for an online newspaper archive. It promptly coughed up a treasure trove of old stories about Kasdan—the same Sara Kasdan on the headstone, and the same Sara Kasdan who had written Love and Knishes.

Whatever ideas I’d had about Kasdan disappeared immediately when I saw her photo, which portrayed a trim, sharp-looking woman with a chic pixie cut and a gleam of shrewd intelligence in her eyes—the polar opposite, in other words, of the woman portrayed on her book’s cover. From a 1953 Courier-Journal story, I learned that she had for a time been the editor of the weekly Kentucky edition of the National Jewish Post; she told a reporter that she tried to make the news an “expression of Jewish life in our community.” Sometimes, the story noted, “she picks out passages from the Talmud and comments on them.” But, it added, “her main [job] is taking care of her husband, James M. Kasdan, a wholesaler, and their three daughters, Debbie, 15, Vicki, 14, and Harriet, 7.”

Kasdan had no other background as a writer; instead, she helped her husband run his infant-wear business and was active in community theater—she appeared in local productions of The Little Foxes and The Miracle Worker, among others. But Love and Knishes, it turned out, had been a bestseller—“Mrs. Kasdan’s book,” the Courier-Journal wrote, “is selling like hot cakes.” It spawned reviews from Wisconsin to Washington state; the Chicago Tribune declared it “both informative and gay” and added that “whether you’re Jewish or not, you’ll want to read it for the chuckles.” Kasdan became a popular guest speaker at temple Sisterhood groups around the country, giving talks that were noted for their humor.

But I was struck less by these references to Kasdan’s wit than by a passage in a 1956 Courier-Journal story. Kasdan, it read, “doesn’t feel cook books belong in an isolated category far removed from other reading matter. Nor does she believe the only purpose a cook book serves is enlightenment for a lady who cannot level a tablespoon without one. The food preferences and food creations of a people or a region are closely bound with the culture and the history of a group, she says. And better group understandings evolve as one begins to learn the small mores of another.”

If anything, Kasdan seemed like a woman ahead of her time.

“She was probably a person ahead of her time,” Debbie Kasdan Straight told me when I tracked her down in Boise, Idaho. “She was working on her college degree for many years off and on with three children, and instrumental in community theater and writing. These were just not things women did.”

Her mother, she added, was one of three sisters who were all talented in the arts. “They had a lot of creativity,” she said. “But there were not too many places to go with it, if you know what I mean.”

Debbie, Kasdan’s oldest daughter, is 79 years old now. She was understandably surprised when I told her who I was and why I was calling; she was a teenager when Love and Knishes was published. And she’s still not entirely sure what inspired her mother to take on the project. “She was just an ordinary cook—I mean, this did not grow out of her own extravagant recipes,” she told me. “I guess the fact that she thought it was a good idea was enough impetus.” But Debbie does have vivid memories of the weeks of recipe testing the family endured. “Her editor wanted [the recipes] to be really precise,” she said. “If I ever see another tzimmes, I will be sick. Oh my god.”

“My mother fooled everyone,” Kasdan’s other surviving daughter, Vicki Moskowitz, told me when I reached her in Louisville. “She wasn’t a bubbe in the least. I remember when my husband and I started dating and he met my mother for the first time, he expected this old bubbe woman with all the trimmings. That’s not what she was at all.”

Like her sister, Vicki remembers all of the recipe testing, and that her mother went on speaking tours after the book was published. But the success of Love and Knishes didn’t spark an illustrious writing career; Kasdan subsequently published So It Was Just a Simple Wedding, a 1961 novel loosely based on Debbie’s wedding, and Mazel Tov, Y’All!, a 1968 Southern Jewish baking book comprised of other people’s recipes. And that was it. I asked Vicki if her mother had wanted to write more books. “I don’t think she did,” she said. “I think she had her fill.”

So Sara Kasdan was nobody’s idea of a bubbe. She also didn’t keep kosher—“it was anything goes as far as eating in our house,” Vicki told me. But she was tenacious, exacting, and thorough, like the best cookbook authors are, and recognized that humor is possibly the best bridge between unfamiliarity and enthusiasm. Love and Knishes certainly wasn’t the only Jewish cookbook of the day—it was sandwiched by Gertrude Berg and Myra Waldo’s The Molly Goldberg Jewish Cookbook in 1955 and Jennie Grossinger’s The Art of Jewish Cooking in 1958. But unlike Berg, who was a well-known TV and radio personality, and Grossinger, who presided over the legendary Grossinger’s Catskills Resort Hotel, Kasdan had neither fame nor the power of an institution behind her. She just had a good idea and the will to see it through.

When I bought my copy of Love and Knishes, I thought I was in on the inside joke, the one where Jews laugh at other Jews and our food’s awesome powers to hobble even the hardiest colon. I knew this joke well—I’d been hearing and telling it for most of my life. What I didn’t know was that Sara Kasdan knew the joke, too, but wasn’t joking: She was determined to keep these recipes alive and available to as many people as possible. As I dug through newspaper clippings and talked to her daughters, I began to think of her as a culinary version of a Colonial Williamsburg tour guide, playing dress-up in the service of historical accuracy and cultural enlightenment. It was a stranger and far better story than the one I’d imagined; in discovering it, I finally saw love where previously I had seen only knishes.