How Kenny Shopsin’s pioneering book Eat Me taught me to stop worrying and love the cookbook.

If there’s one cookbook I remember vividly from my childhood, it was my mom’s copy of Betty Crocker’s Picture Cook Book, 1978 edition. After school I would pore over its throwback recipes, dog-earing pages, scribbling notes, and pretty much doing everything except actually cooking from it. In retrospect, I realize this was a very fat kid thing to do—mentally coveting Chicken à la King and Grasshopper Pie and all these decadent foods I probably shouldn’t eat—but it was a habit that continued well after I lost (most of) my baby fat and eventually became a food writer. And as someone who recently finished coauthoring their first cookbook and considers themselves a pretty serviceable cook, I suppose this is sort of a confession as well: I’ve always been more into reading cookbooks than cooking from them.

I’m probably not alone in that regard—the most common lament about modern cookbooks is that too many flaunt beautiful pictures and crafty prose but end up lying dormant on a coffee table, or worse. Nobody cooks from cookbooks anymore, goes the refrain.

But for me, it’s always felt like a bad habit; that is, not using these intricate publications, which a chef presumably spent months laboring over, for their rightful and intended purpose. But cookbook recipes by nature present a highly composed and often demanding set of requirements, and following that level of instruction isn’t always my strong suit. (I’m more the type to skim the steps and hope I somehow pass the final exam, which doesn’t yield the highest success rate.) Does that make me impatient and a poor planner? Sure, but most of us are. The real issue, I think, is that most cookbooks give you a list of things to cook rather than a framework on how to cook. Once you stray from the dotted lines, you’re on your own.

One of the great exceptions, in my opinion, is Eat Me: The Food and Philosophy of Kenny Shopsin (2008). I probably read it twice a year. I love it that much, mostly because it’s the only cookbook I can think of that actually invites the reader to not follow recipes.

A quick detour: If you’ve never heard of Kenny Shopsin or Shopsin’s General Store, a grocery-store-turned-diner that has operated in a handful of locations around Lower Manhattan since the 1970s, do yourself a favor and read the captivating New Yorker profile written by Calvin Trillin, then go watch the excellent documentary I Like Killing Flies, then ideally go eat a meal at Shopsin’s yourself (without being yelled at or kicked out; Mr. Shopsin is better known for his strict set of house rules than his welcoming hospitality).

I realize this is asking a lot, particularly from someone who maybe can’t be bothered to follow recipes, so let me pass along the crib notes version: Mr. Shopsin is a quintessential foul-mouthed, deep-thinking, no-bullshit Manhattan proletariat, the type that becomes more endangered every year, and his odd little diner, packed with loyal regulars, is a quirky holdover from Greenwich Village at its bohemian apex. Most famously, the menu at Shopsin’s is composed of hundreds upon hundreds of items, each cooked from scratch, and often containing a seemingly disparate array of ingredients combined in ways that make a shocking amount of sense.

But the most impactful aspect of the cookbook is not the story of Mr. Shopsin himself (who passed away in 2018)—though he is undeniably a character—but his philosophy on cooking, whose decades-spanning development he credits to “a combination of psychotherapy and drugs.”

Here’s my favorite summation of that outlook, pulled from the book’s prologue:

I often compare my ideas about cooking to the children’s book Goodnight Moon, by Margaret Wise Brown, where this little boy discovers that everything he needs in his life is in his life already, right in his own room. In a Goodnight Moon world, it’s pretty easy to be a home cook. It’s really not about some terrific skills or expensive high-tech equipment. It’s not even about having the right secret recipe. To be a good cook, to turn out good honest food that satisfies your individual tastes, it is all about having the kind of confidence and self-awareness that comes from Goodnight Moon living, in which you are happy with what is already in your life.

Although Eat Me contains around 120 recipes (most of which are solid, but not necessarily mind-blowing), the recipes are kind of beside the point, in the same way Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance isn’t really about repairing a carburetor. It’s more concerned with the underlying architecture of food-making (one chapter is literally titled “the building blocks of creativity”) laid out in these entertaining, navel-gazing ruminations on everything from cooking eggs the right way (don’t rush them) to why some salad fillings “click” better than others. He advocates for the idea of cooking in stages, of having a posse of staples like marinara or tuna salad available to riff upon, and for a general reimagining of the way we’re predisposed to believe certain foodstuffs should be put together.

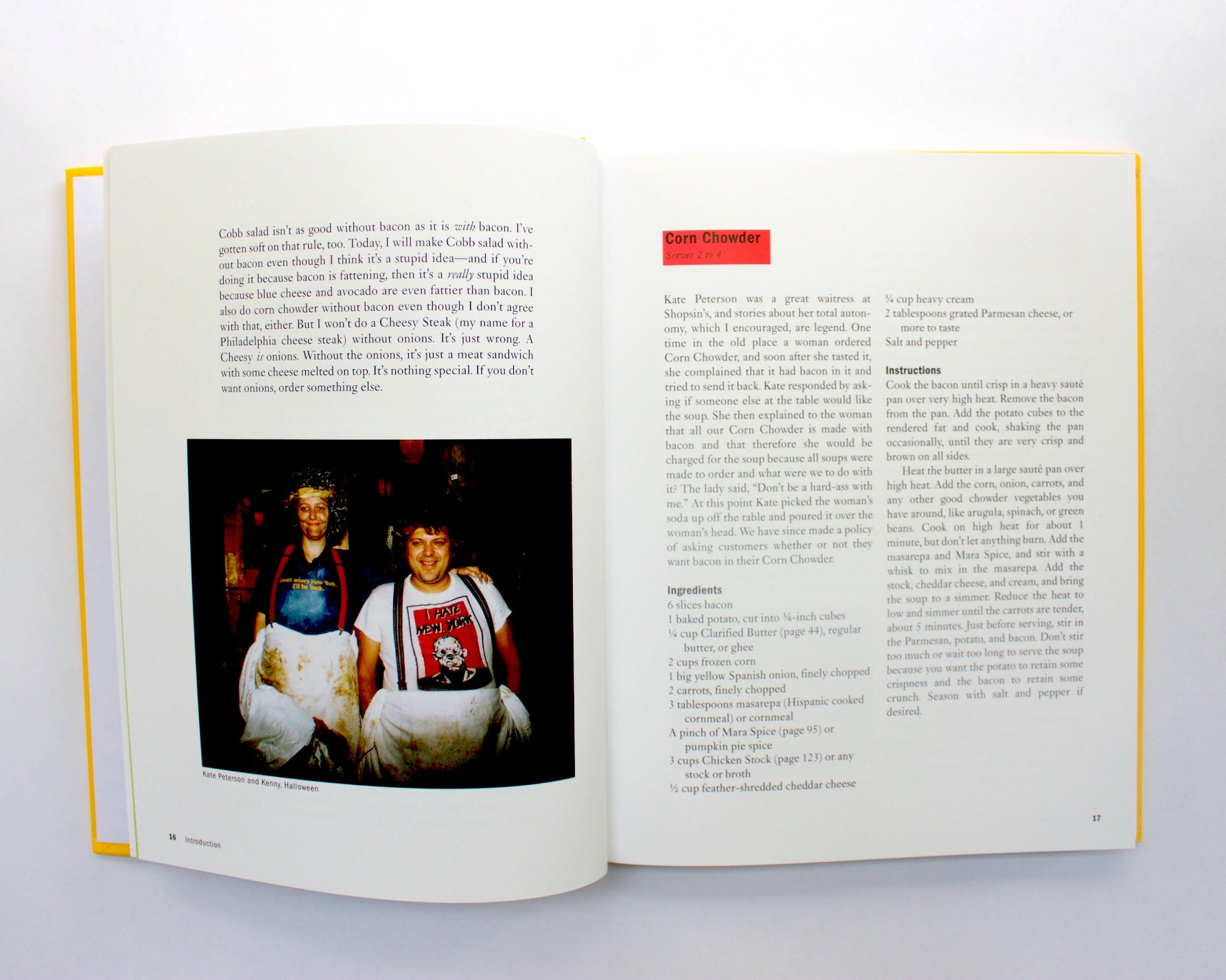

Here’s one example: soup. Most people, myself included, tend to think about making soup in big batches, stewed together in a pot. This has the effect of causing all the flavors to mush together, which is fine for something like chili, but not always preferable in, say, minestrone. The Shopsin doctrine involves cooking the additions to the soup first, as needed, then adding the broth at the end, which keeps the textures and flavors distinct and makes for an infinitely more interesting bowl of soup. This streamlined process is why Shopsin’s the restaurant is able to have dozens of soups (shrimp gumbo, African green curry soup, cream of tomato, Cuban black bean) on its menu on any given day. But it’s also why something as simple as soup theory can have a profound effect on the home cook.

In particular, I have cooked the pseudo-recipe for chicken tortilla avocado soup from Eat Me an untold number of times. The formula is shockingly minimalist, despite how complex and soulful the final result tastes. There’s no dash of cumin, no achiote marinade, no secret twist (though I do add a squeeze of lime at the end, if available). Essentially, you blast a chicken breast on high heat for a few minutes until it’s blackened outside but still pink in the middle and set it aside, then pour some olive oil in a sauté pan and cook down a handful of cabbage, onion, and jalapeño until nicely browned (this is where the deep flavor comes from), then you deglaze with a healthy glug of chicken stock and stir in the sliced chicken and some canned black beans.

Maybe you add some cilantro sprigs at some point—whatever works. Once the broth is hot, you throw in a handful of crushed chips and some avocado and you have tortilla soup—not just any soup, but a life-affirming, satisfying, weirdly empowering soup. And most importantly, if you don’t have one or two of the ingredients on hand, you still end up with something pretty good.

Of course, it would be foolish to claim Mr. Shopsin and coauthor Carolynn Carreño wrote the first cookbook to present simple food in a plainspoken context—Edna Lewis, Marcella Hazan, Simon Hopkinson, and other greats come to mind—but we can certainly agree the grand tradition of cookbooks dedicated to the basics have become far less common than they used to be, and certainly few pull it off with the gruff frankness of Eat Me (“There is nothing I do that a monkey couldn’t do,” Shopsin writes at one point).

The reason for this, to borrow his line of thought, is that in our current culture, we are plagued by always wanting great instead of good, and we’ve become afraid of being mediocre, of being ordinary. If you’re of the mindset that every meal should be a revelation, you’re setting yourself up to become “paralyzed and unsatisfied.” As Mr. Shopsin writes, “most people reach higher than anything they could achieve in terms of their own cooking skills,” which is why they’re never at ease in the kitchen. They miss the true goal of making food for others, which is, as Shopsin puts it, “to take care of [one’s own] emotional instability by cooking.”

Home cooking, I think, is a true heuristic skill. The only way to learn it, much like picking up a new language, it to keep practicing and screwing up until you’ve made sense of these big nebulous concepts and how they fit together. Every person is going to learn distinctly and at a different pace when it comes to cooking. Maybe, then, it’s better to worry less about how something is done than why it’s done; once you understand the why, you can figure out your own how.

The simplest demonstration of this philosophy is found in the recipe for chicken salad: cooked chicken breast (cut into chunks), mayonnaise, salt and pepper (“Bob Dylan, who lived in [my] neighborhood, was hooked on it for years,” Shopsin casually adds). The underlying premise is that since breast meat has a dry texture, you massage the chunks with your fingers until soft and frayed, then stir in the mayo. The frayed chicken wicks the oil from the mayo, leaving behind what Mr. Shopsin calls the “white, creamy, tasty part” to coat the chunks. And like making risotto by slowing stirring in broth, once the chicken molecules have soaked up all the oil they can, the mayo has nowhere else to go. That’s when you’re finished, and season as desired. I don’t make chicken salad very often, but I do think about the physical properties of mayonnaise more than I ever have before.

I emailed Mr. Shopsin recently, both to express my obsession over a book that has been out for nearly a decade and to ask a few questions. His answers were trademark Kenny, but one resonated with me in particular. I asked if he felt he had become more set in his ways over the years. “I continuously change, as does the restaurant,” he wrote. “Everything I cook is cooked as though it was the first time. Even if it seems to be cooked the same way, it is never the same to me.”

Most of the time, when I cook, it’s last-minute improvisation, based on whatever is wilting in the vegetable crisper, or collecting dust in the cupboard. The results are usually not bad, but not amazing either (my wife likes to joke that I’ve never cooked her the same meal twice, which, in the case of my roasted cauliflower sloppy joe or artichoke-goat cheese enchilada experiments, she doesn’t always intend as a compliment). This always felt like half-assing it to me, like I would be better served following someone else’s instructions. But it wasn’t until I read Eat Me that I understood the concept of the finding your way via the anti-recipe recipe, the idea that being conscious of what and how you’re cooking is more crucial than specific guidelines—sort of the Buddhist notion of process over result.

Because when you stop seeing recipes as instructional sets, something amazing happens. You stop worrying if you’re screwing up, and the act of cooking becomes the relaxing, liberating, and even restorative act that it’s meant to be. If the goal of any good cookbook is to enhance your life rather than complicate it, maybe the best books can express ways of thinking that extend beyond just a handful of dishes. Maybe a cookbook has the power to help you become a more aware, more conscious person (okay, that’s a bit of a stretch).

Still, as the Greek philosopher Heraclitus once said, it’s impossible to step twice into the same river. In Shopsin’s terms, that means you’ll never cook that tortilla soup the same way again.