Just like Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Indian Cookery was published in 1961. And just as Julia Child brought authentic French cuisine to the novice home cook, Mrs. Balbir Singh did the same with the cooking traditions of Northern India. But unlike Child, Mrs. Singh was nearly forgotten by history.

Sometime around 1974, Colleen Taylor Sen was expecting a very important guest for dinner. The Indian-American astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar was a renowned professor at the University of Chicago who would go on to win the Nobel Prize. He was also a strict Brahmin vegetarian.

Sen had no idea what to cook for him. She and her husband, Ashish, wanted to make something special, but they were going to need a bit of help and inspiration; Indian vegetarian food can be complex and technically challenging, and as Sen recalls, “We didn’t want to just give him dal and rice.”

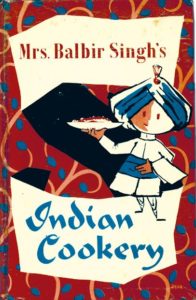

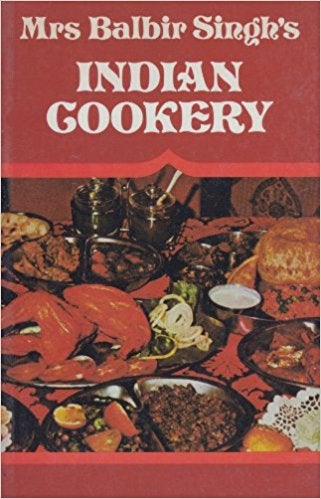

Although they didn’t own many great Indian cookbooks, they did have a copy of Mrs. Balbir Singh’s Indian Cookery. Published in 1961 and written in English, the plain, utilitarian volume was a guide to some of the most popular Indian dishes of the time: mutton roghan josh, whole tandoori chicken and shammi kabab, spinach paneer, dum alu and jackfruit ball curry, sticky gulab jamun and creamy rabri, fragrant pullaos and flat, flaky, crispy, puffed, and stuffed breads. Roughly 200 pages divided into 12 sections, the book contained no photographs—just over 150 straightforward, uncompromising recipes with an exacting list of ingredients and instructions.

Sen, who would go on to write a number of books on Indian food, had already made some of its recipes to great success. If she and her husband were going to have any luck finding something to cook for a strict vegetarian, this book was their best shot.

They decided on two recipes: Kanwal kakri kofta, a lotus root ball curry, and Navrattan pullao, a multicolored rice dish cooked with Indian cottage cheese, tomatoes, peas, and nuts that Singh described as “a pullao amongst pullaos and a jewel amongst jewels.” Both were a hit with the future Nobel laureate, and to this day, Sen remains captivated by Indian Cookery. Thanks to its author’s exhaustive and unwavering quest for authenticity, she says, the book remains “a gold standard for Indian cooking.”

But you’ve probably never heard of Mrs. Balbir Singh. Born in pre-Partition Punjab in 1912 and taught to cook by her mother, Mrs. Singh was determined to write a book of authentically Indian recipes. And when she finally did at nearly age 50, she focused on the food she knew best: rich, decadent curries from Punjab, charcoal roasted kebabs with influences from Pakistan and Central Asia, vegetarian koftas and bhujias often central to a meal, and so much more. Eventually selling hundreds of thousands of copies, her cookbook helped define the quintessential dishes of North India. “In its time, it was the only book that could produce food that tasted like real North Indian food,” says Madhur Jaffrey, the celebrated Indian-born author, actress, and TV personality who wrote more than a dozen books on food and has become one of the most famous names in Indian cooking. “It was a book that Indians would want to cook from, as all the flavors were true and recognizable.” What’s more, says food historian Colleen Grove, Singh’s shahi chicken masala “could be the forerunner to the modern chicken tikka masala recipes,” the roots of which are famously unresolved.

“In its time, it was the only book that could produce food that tasted like real North Indian food,” says Madhur Jaffrey, the celebrated Indian-born author, actress, and TV personality who wrote more than a dozen books on food and has become one of the most famous names in Indian cooking. “It was a book that Indians would want to cook from, as all the flavors were true and recognizable.” What’s more, says food historian Colleen Grove, Singh’s shahi chicken masala “could be the forerunner to the modern chicken tikka masala recipes,” the roots of which are famously unresolved.

To Food Network judge Simon Majumdar, Singh is the Mrs. Beeton or Martha Stewart of India. “I believe in each cuisine, there is always to be found a hero,” he says. “And I think Mrs. Balbir Singh has a good claim to that title for Indian cuisine as anyone.”

Known by her husband’s name (her own first name was Balwant, but she went by Mrs. Balbir Singh throughout her life), she was a homemaker and a quiet pioneer. She taught cooking classes in her kitchen for decades, which shaped her wide compendium of recipes and her ability to instruct. Inspired by her mother’s talent —“an exceptionally good cook,” she noted in Indian Cookery—Singh adapted many of her recipes from the generations before her. But she also researched and collected recipes from other parts of India, speaking to experts, friends, and family who specialized in popular dishes from different states. Her work has influenced generations of housewives, chefs, and cooking stars.

But Singh was a culinary expert before that was something to celebrate. She died in 1994, and despite her influence, fame did not follow—although, as Majumdar points out, “the reality is that there are many juggernauts of cooking going back in the ages who are now long forgotten.”

One who hasn’t been, of course, is Child, and within Majumdar’s comparison of her and Singh lie some uncanny parallels. Before 1961, when both Indian Cookery and Mastering the Art of French Cooking were published, Singh’s path closely mirrored that of her American counterpart. Both women were born in 1912 and followed their husbands’ careers to Europe: Child to Paris and Singh to London. Both subsequently began formal culinary training abroad: Child in 1949 at Le Cordon Bleu and Singh around 1950 at a college on Regent Street in London, where she studied domestic science.

Before Indian Cookery was published, English-language books on Indian cooking were a “hotch-potch attempt” to combine European tastes and Indian flavors, Singh wrote in the cookbook’s opening pages. Her determination to fill that gap was ultimately rewarded: Indian Cookery, published by Mills & Boon in 1961, went through several editions and revisions and won the 1964 German Internelle Kochkunst Ausstellung, a prestigious competition for professional cooks. By 1994, it had sold more than 400,000 copies worldwide.

Before Indian Cookery was published, English-language books on Indian cooking were a “hotch-potch attempt” to combine European tastes and Indian flavors, Singh wrote in the cookbook’s opening pages. Her determination to fill that gap was ultimately rewarded: Indian Cookery, published by Mills & Boon in 1961, went through several editions and revisions and won the 1964 German Internelle Kochkunst Ausstellung, a prestigious competition for professional cooks. By 1994, it had sold more than 400,000 copies worldwide.

After Child and Singh published seminal cookbooks for women in their home countries, Singh became the first culinary expert to appear on Doordarshan, India’s public access network, while Child got her own PBS show, The French Chef, in 1963. But then Child became world famous, her name immortalized through her cookbooks, television shows, books, and later movies like Julie and Julia, while Singh’s contributions to Indian cooking have been largely forgotten.

No one has determined why that is, though looking at Singh and the era in which she lived allows for conjecture. While her reputation spread through word of mouth, she was never hugely advertised for her work. “She was just magical in the kitchen,” says Singh’s granddaughter, Pallavi Sitlani, 49, who lives in London. However, Singh was modest, and that made her unwilling to seek the spotlight. “She was not a self-promoter,” Sitlani says. Even if she had sought it, she lived in a time in India when most women were not celebrated for their work, particularly in the kitchen.

Plus, cooking was not viewed as a path to fame until the 1970s, when TV began to help promote authors like Jaffrey, whose first cookbook, An Invitation to Indian Cooking, was published in 1973. But even then, it took a certain kind of cookbook to capitalize on the public’s desire for information. Indian Cookery, Jaffrey points out, was not meant for amateurs: “It is a no-nonsense book that does not entice a novice into the fold.”

Take Singh’s recipe for Navrattan pullao, which Sen made for Chandrasekhar all those years ago. The dish requires 27 ingredients—importantly, cashew nuts, sultanas, Indian cottage cheese, pistachios, and almonds—and is defined by its alternating layers of basmati rice colored green, red, and white. In one of several dozen steps, Mrs. Singh recommends putting hot charcoals on the lid so the food coloring really seeps in.

Indian Cookery is a textbook on cooking in North India—deeply influenced by the cuisine of Punjab, Kashmir, and India’s ancient connections to Central Asia, China, and Pakistan, which had been a part of the country until Singh was in her 30s. (It also includes a smattering of typically South Indian specialties, such as dosa and sambar.) Early chapters of the book are dedicated to kitchen essentials, like utensils, weights and measurements, and recipes for yogurt and homemade masala powders. “The author,” Singh wrote, “does not advocate the use of packaged curry powders or gourmet powders.”

Singh was a gifted writer, and her meticulous recipes and insights on Indian cuisine filled both Indian Cookery and her 1994 book, Continental Cookery for Indian Homes. She was uncompromising in her tastes, and she wasn’t about to yield to the colonial influence that pervaded her formative years. “Rice served in British restaurants is a mere apology for a pullao,” she wrote in Indian Cookery’s introduction to rice. And she was nothing if not confident in her authority. “Indian food has an uncanny charm and those who once taste Indian food find that all other food is insipid and tasteless in comparison,” she asserted proudly.

Today, the curry powders Singh dismissed more than five decades ago as “practically unknown in India” are now sold all over the world. They have made Indian cooking accessible to home cooks who don’t want to stock a multitude of spices. And for her descendants, they are a way to honor Singh’s contributions to Indian cooking.

Last December, after spending years discussing how to revive her grandmother’s recipes—and restore her name to its rightful place in culinary history—Pallavi Sitlani (the daughter of Singh’s only son, Deepak) and her husband, Sunil, 50, launched Mrs. Balbir Singh, a brand of spice blends that were first detailed in Indian Cookery. “We’ve literally taken those exact same proportions in the book,” Sunil says.

The process started in their kitchen and eventually made its way to a facility outside London that roasts and blends the spices according to Singh’s specifications. The blends, which are shipped around the world, include mixtures for some of Singh’s best-known recipes: Shahi chicken masala, garam masala, amritsari chana masala, and a recently launched tandoori BBQ rub.

More than 30 years after Indian Cookery‘s last printing, the Sitlanis’ next step will be to republish the cookbook—or more specifically, a new version that maintains the integrity of Singh’s recipes but updates them for today’s home cooks. They plan to add photographs and revise some of the older cooking terms, measurements, and ingredients. The original Indian Cookery will also soon be available on CKBK, a digital subscription service for noteworthy cookbooks.

Though Mrs. Singh is unlikely to achieve the level of fame amassed by Child over her career, there is one place where her influence is remembered. After moving back to India from London, Mrs. Singh began teaching home science at New Delhi’s Lady Irwin College around 1956. Shortly thereafter, she left the college and began teaching cooking and homemaking classes in her own kitchen full-time.

Her at-home students were mostly young wives and brides-to-be, and the classes quickly grew from six people twice a week to 40 per class six days a week. Singh taught 10-class courses that usually took about a month to complete. In teaching a generation of women how to cook, those classes also empowered and inspired them to be independent. Not long ago, Sitlanis received an email from a woman who said her mother took Singh’s classes in the ’60s and was transformed from a shy young woman into an accomplished cook. Her mother’s knowledge, learned from Singh’s classes, was eventually passed down to her.

As with her recipes, Singh was methodical in her class preparations, meticulously organizing spices, ingredients, and measurements before each session. Singh taught from handwritten recipe cards and kept notebooks that eventually turned into the basis for Indian Cookery.

A lot has been said about the intricacies of Singh’s cookbook, but being daunting was never her intention. “It’s not the Indian cookery which is complicated but the recipes which are exhaustive,” she wrote in Indian Cookery. Perhaps she was ahead of her time, but the scientific approach that characterized Singh’s cooking more than 50 years ago reads as a blueprint for so many later cookbooks that have patiently demystified non-Western cuisine for Western audiences.

Singh didn’t see Indian food as a secret to be guarded; she wanted you to learn. Read her cookbook and she’ll break down her method for making ghee (clarified butter) or garam masala. She’ll tell you the best way to cook a mutton pullao and walk you through the two dozen steps to the sweetest ras malai.

She didn’t just believe Indian food was unparalleled. She believed you could make it, too.

“Her legacy is showing how things should be done, if one wants to do them properly,” Majumdar says. “I am sure now many people have family recipes for X, Y, or Z and don’t realize that they come from Mrs. Singh.”